By MICHAEL R. SISAK and LARRY NEUMEISTER

NEW YORK (AP) — As the Justice Department gets ready to release its files on sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and his longtime confidant Ghislaine Maxwell, a court battle over sealed documents in Maxwell’s criminal case is offering clues about what could be in those files.

Immigrant with family ties to White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt is detained by ICE

Supreme Court won’t immediately let Trump administration fire copyright office head

Pushing an end to the Russia-Ukraine war, Trump looks to his Gaza ceasefire playbook

Trump administration says lower prices for 15 Medicare drugs will save taxpayers billions

New prosecutor won’t pursue charges against Trump and others in Georgia election interference case

Government lawyers asked a judge on Wednesday to allow the release of a wide range of records from Maxwell’s case, including search warrants, financial records, survivor interview notes, electronic device data and material from earlier Epstein investigations in Florida.

Those records, among others, are subject to secrecy orders that the Justice Department wants lifted as it works to comply with a new law mandating the public release of Epstein and Maxwell investigative materials.

The Epstein Files Transparency Act was passed by Congress and signed by President Donald Trump last week.

The Justice Department submitted the list a day after U.S. District Judge Paul A. Engelmayer in New York ordered the government to specify what materials it plans to publicly release from Maxwell’s case.

The government said it is conferring with survivors and their lawyers and that it will redact records to ensure protection of survivors’ identities and prevent the dissemination of sexualized images.

“In summary, the Government is in the process of identifying potentially responsive materials” that are required to be disclosed under the law, “categorizing them and processing them for review,” the department said.

The four-page filing bears the names of the U.S. attorney in Manhattan, Jay Clayton, along with Attorney General Pam Bondi and Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche.

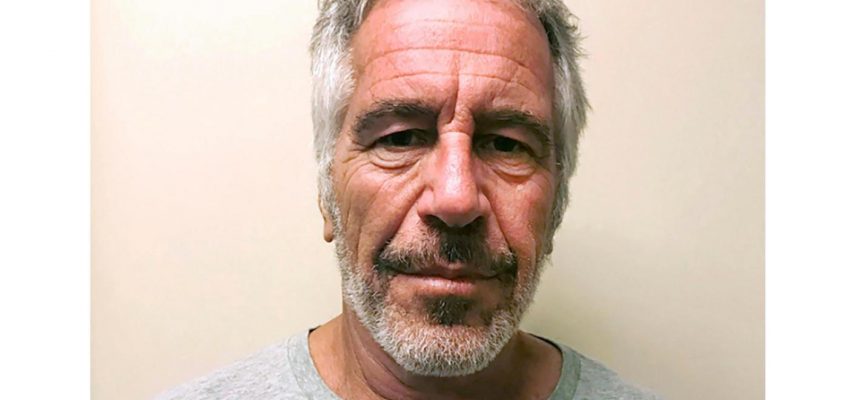

FILE – In this July 30, 2008, file photo, Jeffrey Epstein, center, appears in court in West Palm Beach, Fla. (Uma Sanghvi/The Palm Beach Post via AP, File)

Also Wednesday, a judge weighing a similar request for materials from Epstein’s 2019 sex trafficking case gave the department until Monday 1 to provide detailed descriptions the records it wants made public. U.S. District Judge Richard M. Berman said he will review the material in private before deciding.

In August, Berman and Engelmayer denied the department’s requests to unseal grand jury transcripts and other material from Epstein and Maxwell’s cases, ruling that such disclosures are rarely, if ever, allowed.

The department asked the judges this week to reconsider, arguing in court filings that the new law requires the government to “publish the grand jury and discovery materials” from the cases. The law requires the release of Epstein-related files in a searchable format by Dec. 19.

FILE — Audrey Strauss, Acting United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, speaks during a news conference to announce charges against Ghislaine Maxwell for her alleged role in the sexual exploitation and abuse of multiple minor girls by Jeffrey Epstein, July 2, 2020, in New York. (AP Photo/John Minchillo, File)

Epstein was a millionaire money manager known for socializing with celebrities, politicians and other powerful men. He killed himself in jail a month after his 2019 arrest. Maxwell was convicted in 2021 of sex trafficking for luring teenage girls to be sexually abused by Epstein. She is serving a 20-year prison sentence.

In initial filings Monday, the Justice Department characterized the material it wants unsealed in broad terms, describing it as “grand jury transcripts and exhibits.” Engelmayer ordered the government to file a letter describing the materials “in sufficient detail to meaningfully inform victims” what it plans to make public.

Engelmayer did not preside over Maxwell’s trial, but was assigned to the case after the trial judge, Alison J. Nathan, was elevated to the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Tens of thousands of pages of records pertaining to Epstein and Maxwell have already been released over the years, including through civil lawsuits, public disclosures and Freedom of Information Act requests.

In its filing Wednesday, the Justice Department listed 18 categories of material that it is seeking to release from Maxwell’s case, including reports, photographs, videos and other materials from police in Palm Beach, Florida, and the U.S. attorney’s office there, both of which investigated Epstein in the mid-2000s.

Last year, a Florida judge ordered the release of about 150 pages of transcripts from a state grand jury that investigated Epstein in 2006. Last week, citing the new law, the Justice Department moved to unseal transcripts from a federal grand jury that also investigated Epstein.

That investigation ended in 2008 with a then-secret arrangement that allowed Epstein to avoid federal charges by pleading guilty to a state prostitution charge. He served 13 months in a jail work-release program. The request to unseal the transcripts is pending.