By MATT BROWN and LINLEY SANDERS

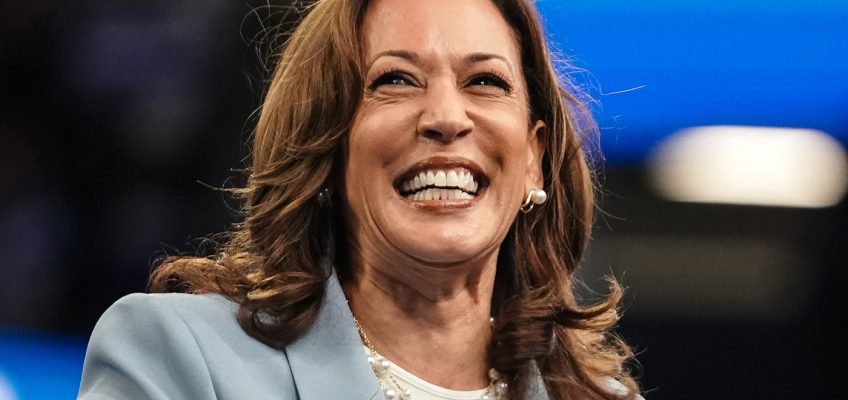

WASHINGTON (AP) — Black registered voters have an overwhelmingly positive view of Vice President Kamala Harris, but they’re less sure that she would change the country for the better, according to a recent poll from the AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

The poll, which was conducted in mid-September, found about 7 in 10 Black voters have a somewhat or very favorable view of Harris, with few differences between Black men and women voters on how they view the Democratic candidate. Younger and older Black voters also had similar views of the vice president.

Black voters’ opinions of former President Donald Trump, by contrast, were overwhelmingly negative, underscoring the challenges that the Republican candidate faces as he seeks to erode Harris’ support among Black men. Black voters are an important Democratic constituency, and few are aligned with the Republican Party. According to the survey, two-thirds of Black voters identify as Democrats, about 2 in 10 identify as independents and about 1 in 10 identify as Republicans.

But the poll also found that despite this dramatic gap in views of the candidates, Black voters are less certain of whether Harris would set the country on a better trajectory, or make a substantial difference in their own lives. Only about half of Black voters say “would change the country for the better” describes Harris very or extremely well, while about 3 in 10 say it describes her “somewhat well” and about 2 in 10 say it describes her “not very well” or “not well at all.” And only about half believe the outcome of this presidential election will have “a great deal” or “quite a bit” of impact on them personally, an assessment that’s in line with Americans overall.

“The Democratic Party is not strong enough for me,” said Raina Johnson, 53, a safety case manager in Chicago. Johnson predicted that Harris would “try to do something for the people” but she felt that Harris would be limited as it was “with (Barack) Obama, because the Republican Party shut him down.”

While Johnson felt that the stakes of the election were extremely high, she did not think it would have a large personal impact on her.

“Because I’ll still live my life. I’ll just have to roll with the punches,” she said.

Most Black voters think Harris is better on the issues

When asked which candidate would do a better job handling their top issues, including the economy, health care and crime, Black voters had the same answer: Harris.

Like voters overall, about 8 in 10 Black voters said the economy is one of the most important issues to their vote. But about three-quarters of Black voters said health care was one of their most important issues, compared to slightly more than half of registered voters, and they were also more likely than the electorate as a whole to say gun policy and crime were top issues.

Related Articles

Analysis: Harris signals fight with Congress over agenda in ’60 Minutes’ interview

Trump says migrants who have committed murder have introduced ‘a lot of bad genes in our country’

For US adversaries, Election Day won’t mean the end to efforts to influence Americans

Turning Point wants to revolutionize how Republicans turn out voters. Some are skeptical

How important is Wisconsin? Trump’s now visited 4 times in 8 days

In all of those areas, as well as on other topics like abortion and climate change, Harris held a commanding advantage over Trump among Black voters. But the size of that edge was bigger on some issues than others. About 6 in 10 Black voters said Harris was better positioned to handle the economy, while about 2 in 10 said this about Trump, giving Harris about a 40-point advantage. On abortion policy, she had around a 60-point advantage over Trump.

The Trump campaign has stepped up with some outreach to Black communities this year. The former president’s campaign believes that his message on the economy, immigration and traditional values can make notable inroads into the Democrats’ traditional base of support among Black voters, especially younger Black men.

Rod Wettlin, a retired Air Force veteran in Surprise, Arizona, who wants greater action on issues like health care and immigration, said he was deeply opposed to Trump and was concerned about the implications of the election for American democracy.

“What’s going on now is the culmination of a lot of stuff that’s been in our face for years,” said Wettlin. “Hopefully after the election it is civil, but these cats out here are already calling for bedlam. And that’s their right, I fought for them to have that right. But don’t infringe on mine.”

There are signs that some groups of Black voters see Harris as a stronger figure, though. Black women voters and older Black voters were especially likely to describe Harris as someone who would “fight for people like you,” compared to Black men and younger Black voters.

FILE – A supporter holds up a sign as Republican presidential candidate former President Donald Trump speaks at a campaign rally at Trump National Doral Miami, July 9, 2024, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell, File)

Black voters view Trump negatively, and some are skeptical about Biden

Relatively few Black voters have a positive view of Trump, or see him as a candidate who has important qualities for the presidency. The poll found that about 8 in 10 Black voters have a somewhat or very unfavorable view of Trump, while just 15% have a somewhat or very favorable view. About 1 in 10 said “would change the country for the better” or “would fight for people like you” describes Trump at least very well, and a similarly low share of Black voters said that Trump would make a good president.

“I think we’re headed in the right direction if Kamala Harris gets it,” said Roslyn Coble, 63, and a resident of Oakboro, North Carolina. “But if Donald Trump gets it, it’s going to be bad. He already told us what he’s going to do. He’s going to be a dictator.”

About 7 in 10 Black voters say the phrase “will say anything to win the election” describes Trump at least very well.

In a sign of how former President Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw as the Democratic candidate in July may have altered the race, only 55% of Black men voters have a favorable view of Biden, compared to 7 in 10 Black women voters.

“He did his best,” said Wettlin. He said that Biden should have bowed out of the presidential race far sooner and was skeptical of some of his achievements.

Black voter engagement organizations say they have also seen a burst of energy from voters and advocates since Harris’ entrance into the race, and both the Harris and Trump campaigns are continuing to focus on this group.

The Trump campaign has been conducting listening sessions and community events in Black neighborhoods in cities like Philadelphia, Detroit and Milwaukee. The campaign has also coordinated a “Black Voices for Trump” bus tour across cities in September. Meanwhile, the Harris campaign has held a number of events geared toward Black voters, especially Black men, and has deployed a number of high-profile surrogates, including lawmakers, celebrities and civil rights leaders, to Black communities in recent weeks.

The poll of 1,771 registered voters was conducted Sept. 12-16, 2024, using a sample drawn from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The margin of sampling error for registered voters is plus or minus 3.4 percentage points.