Articles

How to pick the best online slots games

Gamble Online slots games in the Gambling establishment.com Asia

Position Provides

The best slot machine game so you can victory real cash is actually a position with a high RTP, plenty of extra provides, and you can a great opportunity at the a good jackpot. Certain slots give have which might be adorable but wear’t shell out a lot. Read the profits to have icons and the icons conducive in order to multipliers, free spins, and other added bonus rounds. Each other online harbors and you will real cash harbors provide benefits, approaching varied player needs and you can choice. To help you be eligible for the top progressive jackpot, people usually have to put the limit choice.

Even though, including everything else all of them has its solid serves and that could be crucial for you. So you can find an in depth malfunction of any casino mentioned here centered on specific has including good for cellular gambling or to own slots admirers a little while after. But very first one thing earliest, we have found the listing of greatest-ranked gambling enterprises. The fresh magnifier means the newest scatter icon and three or maybe more of them give you eight Mystery Rats position 100 percent free spins, where wild signs are still gooey. You can also property power-upwards signs one randomly frequently include one to, a couple of, or about three beliefs on the property value the brand new wilds.

How to pick the best online slots games

Having its enjoyable theme, multiple incentive features, and amount of betting alternatives, it’s a https://free-daily-spins.com/slots/cash-cauldron choice for each other the fresh and you can educated players. The additional mystery part of the fresh chests, along with the prospect of high wins, helps it be a casino game value examining. The brand new Secret Mice slot game was launched inside the September 2024 by the Pragmatic Play. Like any ports, the video game contains of a lot paying signs, bonuses, features, and you will winnings. You’ll encounter a detective mouse, believe mouse, mouse officer, cover, pipe, and the royal suite from A great, K, and you will Q.

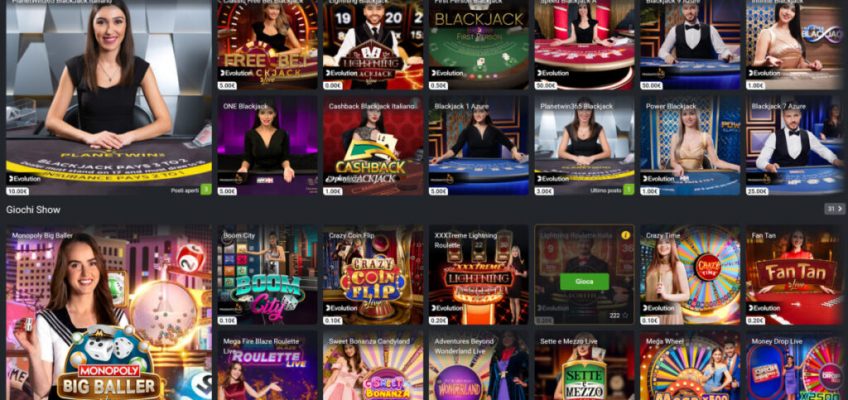

Las vegas Crest has an entire alive specialist section and you will fish connect online game on the specialization video game area. Vegas Crest takes another strategy with its games alternatives by the holding offbeat ports-type of video game including chain reactors that have stacked gems and degree. They also emphasize real cash bingo, devoting an entire point so you can they. Deposit running takes anywhere from minutes in order to 2 days. The bonus controls also provides 24 areas away from multipliers you to definitely enhance the fun.

Gamble Online slots games in the Gambling establishment.com Asia

Going after the individuals elusive orbs to the Keep & Twist feature have the fresh thrill large, when you are 100 percent free video game put an additional covering away from excitement. Lightning Buffalo Connect isn’t just a game title; it’s an enthusiastic adventure you to claims endless fun plus the chance to hook up the fortune which have enormous advantages. If it appears about three or more minutes, the new Secret Bunch symbol usually punctual their reels to alter to help you gold. They’re going to up coming display any investing signs (excluding the new Nuts icon) and so they pay on the all ten winlines.

The online slots listed here are interesting and fun, with plenty of exciting provides to keep your hooked. Karolis Matulis are an enthusiastic Search engine optimization Posts Editor at the Gambling enterprises.com with well over 5 years of expertise from the online gaming community. Karolis has authored and edited all those position and gambling enterprise reviews and contains played and you will tested thousands of on the web position game. So if there is certainly an alternative position identity developing in the near future, you greatest understand it – Karolis has already tried it.

Have fun with the greatest real money ports out of 2025 at the all of our better casinos now. It’s not ever been easier to victory large on your favourite position online game. Various other video game that we strongly recommend you test ‘s the 88 Fortunes on the web slot discharge from the Shuffle Grasp. You’ll find a comparable wonderful tortoise on the one out of the fresh China Secret slot machine appearing about this games’s reels. It offers four independent jackpots in your case to try and victory, when you are totally free spins and wilds are also energetic regarding the game.

Some casinos on the internet are 100 percent free spins as an element of their greeting incentives, and others render them due to lingering offers. But even though you never see 100 percent free spins, any bonus cash is a hook. It is even needed to experience ports with added bonus money, as they features an excellent 100percent sum to help you wagering criteria. Therefore, you’re going to get the full really worth from your own bonus once you spin those reels. Alive slots provide an exciting and you will varied gambling sense, that have an array of video game featuring designed to remain participants engaged and you may entertained. On the non-stop action from twenty-four/7 slots to the unique technicians and you will thrilling jackpots, there’s some thing for everyone in the wonderful world of real time slots.

We could give you out to gamble people slot your come across online. According to your standard, you could potentially come across the detailed slot machine games in order to play for real money. Lower than, we’ll emphasize some of the best online slots for real money, in addition to penny ports that enable you to wager short if you are setting out to own big benefits. When you’re Us gambling enterprises offer particular vintage game – the online local casino globe is stuffed with innovative betting studios.

Position Provides

It’s the unique have one to set for each and every game apart, doing an appealing and you will fulfilling experience for participants. Of imaginative aspects in order to lucrative jackpots, these features increase the full game play and sustain players going back for lots more. Let’s discuss some of the standout provides which make live ports a hit in the gambling enterprise world. To own a game title you to definitely merges the new thrill out of large gains having creative gameplay, Lightning Buffalo Hook shines. Manufactured by Aristocrat, this game features the widely used Keep & Twist aspects, offering players the ability to enhance their effective tips.

For individuals who’re also new to free gambling enterprise harbors, these may sound challenging. In reality, these features could make to experience free slots zero packages for fun far more fun. Within the 2025, your wear’t need to follow 100 percent free cent slots just. Such brand new video game include plenty of enjoyable incentive rounds and you can totally free spins.

You may also pick the full five-reel pile from Wonderful Pharaoh features. To safeguard on your own when to experience to the mobile, simply relate with secure Wi-fi (otherwise 4/5G) associations and always lock the device having a good passcode, fingerprint, or deal with ID. r face ID. You might be safe to the local casino side, and you can hat do make sure your sense is always safe and fair. The major multiplier wager in the primary game is the 10x commission regarding the //€//€10 bet.

On top of that, the brand new totally free local casino ports come with unbelievable picture and special effects. By far the most colourful and you will creative video game within the web based casinos, ports might be great enjoyment. Nevertheless want to choose the best online slots games which get you the most funds and you may excitement.