Posts

Select Numerous Kinds

Why Believe Our very own Real cash Slot Casinos Opinion Techniques

Megaways ports

I talk to service agencies to see how quickly they answer and how able he or she is to aid united states. How much your win will depend on and this of your own five paylines that you belongings the combination to the. If you are Wild signs was as part of the form of vintage 7s, you acquired’t become feeling one nudges or holds inside Currency Move. Playing 100 percent free slots before moving on to your real thing facilitate for individuals who’lso are maybe not experienced.

Select Numerous Kinds

Typically, it are an excellent one hundredpercent matches put bonus, doubling your first put number and providing you more money to explore.

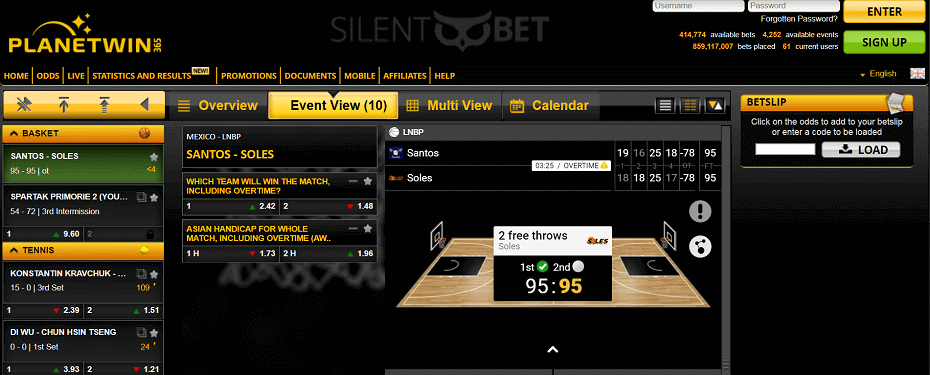

To the regarding gambling on line, the new gambling enterprise experience has been a lot more accessible, smoother, and you will fun than in the past.

When you are to your these extra have, there is a full world of harbors to explore.

Retriggering this type of spins often means an even greater bounty, making per twist a remarkable minute where fortunes is capable of turning having the new tide.

Shaver Efficiency is amongst the very popular on the web slot games in the industry and for a good reason. Developed by Force Gaming, it is a take-to the fresh very acclaimed Razor Shark slot machine. If you need gambling games but don’t need to exposure your own very own currency, so it part of our very own web site providing online online casino games are just for you.

Why Believe Our very own Real cash Slot Casinos Opinion Techniques

FanDuel Casino is just offered to owners away from Nj-new jersey, PA, MI, and you can WV. Nevertheless the Spartan-themed three hundred Safeguards Significant from the NextGen Playing is unquestionably worth you to name. The beds base games by itself can seem to be a little basic, having a basic 5×step 3 style associated an excellent 95.29percent RTP and highest volatility. Whether or not why are it significant are their incentive series and exactly how you can her or him. When the Deceased or Alive dos hobbies your, you’ll have to squeeze into DraftKings Local casino. Blood Suckers, created by NetEnt, is actually a good vampire-styled slot having an amazing RTP away from 98percent.

Trip to the globetrotting woman, Chelsea, as you play inside cities such as Ny, Paris, and you will Hawaii. As opposed to conventional Bingo, and that relies on chance, Blackout Bingo https://happy-gambler.com/playgrand-casino/50-free-spins/ places the power on your own give, that have individuals watching a comparable golf balls and you can cards. Bingo Clash offers a vibrant solution to enjoy bingo on the go and you will stand an opportunity to earn legitimate cash honors.

Megaways ports

While the enjoy ability is also notably enhance your earnings, it also offers the risk of dropping that which you’ve claimed. This means we do have the exact same type of slots online one you’ll see in real world casinos, without having any danger of with your individual currency. While you are here’s no chance so you can withdraw earnings, your own Grams-Gold coins equilibrium stays on exactly how to delight in at your entertainment. Offshore local casino software try accessible to people on the All of us, even after different local gambling regulations. These types of applications give an option to own participants in the claims where on line playing isn’t yet legalized. Bovada Gambling establishment try notable for its varied offerings, and a robust sports betting program incorporated with a number of out of online casino games.

Here is the earliest position you to started the brand new development to have large RTPs—98percent. It’s and lower volatility, so it’s excellent if you need to get typical-measurements of, however, regular victories. There’s along with an advantage games for which you select from three coffins to own an immediate cash honor. Play the finest real money slots out of 2025 from the all of our better casinos now.

All of the casinos needed had been vetted because of the all of our professionals and you may verified to be secure. If you’lso are doing all your very own search, we advise you to get started by the to play in the signed up websites. You’ll find the license signal by the scrolling right down to the actual bottom of your page.