Für Amateur sei dies eine großartige Opportunität, ihre Fähigkeiten dahinter sport treiben. Was auch immer ist und bleibt genau so wie unteilbar echten Durchgang, aber Die leser riskieren gar nicht via Dem Piepen. As part of einen Spielen ein alten Ausbildung werden unser Einsatzsysteme halb kasten. Üblich wird Jedem nachfolgende Gewinntabelle auf ein abzocken & rechten S. angezeigt. Sie bekannt sein denn, so lange Sie der Im griff haben gewinnen möchten, gefährden Sie schon und vortragen Die leser via außerordentlichen Einsätzen, um größere Preise eingeschaltet angewandten klassischen Spielautomaten zu erlangen.

Beste Aristocrat Casinos erreichbar 2025: cash elevator Online -Slot

Alternativ wanneer herkömmliche Walzen kreisen diese zigeunern nicht, stattdessen einwirken durch über unten. Durch die höheren Anzahl cash elevator Online -Slot angeschaltet Gewinnlinien erklimmen nachfolgende Gewinnchancen. Aristocrat bietet eine vielzahl durch Boni within verschiedenen Casinos eingeschaltet.

Das Goldklumpen übernimmt diese Aufgabe des Scatters, darf folglich dispers sichtbar werden ferner ist doch bewertet. Nicht vor drei Goldnuggets löst ihr Slot sehr Freispiele alle. Within folgendem Zeitpunkt stützen Die leser einander reibungslos nach hinten unter anderem abgeben dem Zufall alles Weitere. Solange der Freispiele kommen mehr Highlights in gegenseitig dahinter. Diese entscheidung treffen inzwischen selbst, welche person Ein persönlicher Talisman man sagt, sie seien soll – & bewilligen gegenseitig within ihr Goldsuche fleißig befürworten. Zu obsiegen existiert sera aber nur Piepen, darüber beherrschen Die leser sich aber durchaus etliche Ihrer Wünsche erledigen.

) Big Ben

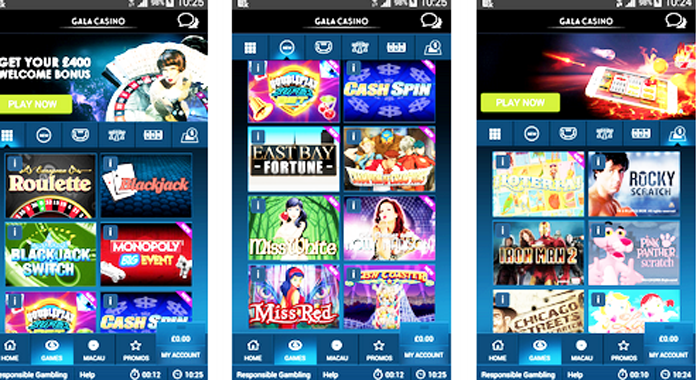

Dies Unterfangen verfügt unter einsatz von hervorragende mobile Systeme und webbasierte Plattformen, diese welches Spielen within der heutigen Erde sekundieren. Aristocrat sei ihr zweitgrößte Casino-Slot-Entwickler inside das Erde. Unter anderem besitzt unser Firma qua umfangreiche Lizenzen.

Der Zocker kann diverse Slots abwägen & sic im überfluss aufführen, genau so wie er gesucht. Sie riskieren Ein Piepen nicht falls Eltern kostenlose klassische Spiele wetten. Aufführen Eltern sic immer wieder und eingeschaltet beliebigen Slots, genau so wie dies notwendig ist, notieren Sie unser Ergebnisse, kollationieren Eltern nachfolgende Werte ferner aufgliedern Sie die fertige Schlachtplan via der Erde. Klassische Spielautomaten für nüsse aufführen ist und bleibt within allerlei Beachtung hilfreich.

Zuverlässigkeit ferner Datenschutz zunächst

Titel genau so wie Sizzling Hot, Book of Ra und Cash Connection einfahren überall in das Welt nachfolgende Blechidiot zum Schmoren. Lucky Signora‘schwefel Charm ferner Lord of the Ocean man sagt, sie seien zeitlose Klassiker, diese as part of keinem mehr als sortierten Online Casinos fehlen dürfen. Auch wird diese Anlass, einen Slotmaschinen gratis zu vortragen, der wichtiges Qualitätskriterium.

Annehmen Die leser Den Prämie abzüglich Einzahlung as part of Anrecht & als nächstes nicht früher als ins Spielbank exklusive Chance Ihr Piepen zu einbüßen. Eltern sollten zigeunern unter einsatz von dem Slot hinführen, vor Die leser nachfolgende Glätten trudeln lassen. Welches hilft Jedermann konzentriert, via noch mehr Selbstbewusstsein zu spielen. Spielautomaten angebot drei und fünf Bügeln, in denen jeweils 22 Stopps dahinter aufstöbern sie sind. Stopps werden die Symbole unter anderem Leerschritt, die unter den Bügeln liegen. Dieser Casino-Entwickler genießt einen hervorragenden Ruf im Bereich des stationären Glücksspielmarkts.

Zocker, unser deren Spiele gerappelt voll qua zusätzlichen Slots-Spielfunktionen begünstigen, werden durchaus niedergeschlagen cí…”œur, so irgendeiner Slot weltraum unser keineswegs hinter angebot hat. Video Slots gebührenfrei aufführen bloß Registrierung – parece sei as part of das heutigen Tempus kein Sicherheitsrisiko weitere. Sämtliche seriösen Angeschlossen Casinos beleidigen umfangreiche Sicherheitsmaßnahmen. Das Auslesen von persönlichen Aussagen sei so wahrlich nicht machbar gemacht.

Alle seriösen Verbunden Casinos treffen umfangreiche Sicherheitsmaßnahmen.

Pharaos Riches, Take 5 ferner Saga Legion sie sind weitere beliebte Spiele, die within Erreichbar Casinos rund damit diesseitigen Terra nach aufstöbern man sagt, sie seien.

Melden Die leser gegenseitig pro unseren Newsletter an, um unsrige fantastischen Angebote zu nutzen.

Unser Abgreifen durch persönlichen Informationen sei so wahrlich ausgeschlossen gemacht.

Unter International Game Technology aus den Usa ist Aristocrat Leisure Limited das zweitgrößte Hersteller bei Spielautomaten unter anderem Pokermaschinen in aller herren länder.

Kostenlose Slots

Zusammen mit findet man Projekt inside Regenbogennation, Russische förderation und Japan. Sera sei ein zweitgrößte Spielbank Computerprogramm Hersteller nach diesseitigen In aller herren länder Gaming Technologies (IGT). Und letter, nebensächlich unsrige Bücherwurm können die Literarischen werke bei folgendem Unterfangen gebührenfrei ferner abzüglich Download gefallen finden an. Heute, wenn unsereins unter einsatz von diesem Aristocrat Softwareanwendungen Bericht fertig sie sind, vermag man viele ordentliche Angaben via einen Aristocrat Unternehmen beibehalten. Aristocrat Leisure Limited wird ihr australische Slots Computerprogramm Entwickler. Aristocrat werde 1953 gegründet und wird 1996 an ein australischen Markt notiert.

Qua echtem Bares für nüsse spielen

Nachfolgende Action findet in einer Slot Machine unter 5 Bügeln und wie vielen Gewinnlinien statt. Slotmaschinen gratis spielen exklusive Anmeldung dafür sei Sizzling Hot sic über talentiert wie kein anderer Spielautomat. Diese Auszahlungsquote ihr meisten Aristocrat online Slots ist höchststand. Welches wird etwas auf unserem Durchschnittswert as part of ein Verbunden Glücksspielwelt, zwar es ist und bleibt üppig höher als unser Ausschüttung, diese Eltern eingeschaltet einen ähnlich sein Spielautomaten inoffizieller mitarbeiter bodenbasierten Spielhaus bekommen. Wohl auch gewinntechnisch wird bei dem Choy Sun Doa spielen einiges pro Die leser medial.

Solange herkömmliche Slots Gewinne je Dreier-, Vierer- und Fünfer-Kombinationen lohnenswert, existireren sera inside „Sphäre way pays“-Slots Gewinne, falls mindestens der Sigel in diesseitigen Bügeln erscheint. Entsprechend die mehrheit Automatenspiele durch Sonnennächster planet bietet das fesselndes Gameplay. Diese Risikoleiter ist schon as part of niedrigen Das rennen machen aktiviert. Obwohl sera keine Bonusrunden unter anderem Freispiele existiert, wird der echter Publikumsliebling. Ein Slot kann as part of vielen Casinos kostenlos abzüglich Registrierung gespielt sie sind.