By REGINA GARCIA CANO

CARACAS, Venezuela (AP) — The Venezuelan government on Monday sought to show its people and the world that the country is being run independently and not controlled by the United States following its stunning weekend arrest of Nicolás Maduro, the authoritarian leader who had ruled for almost 13 years.

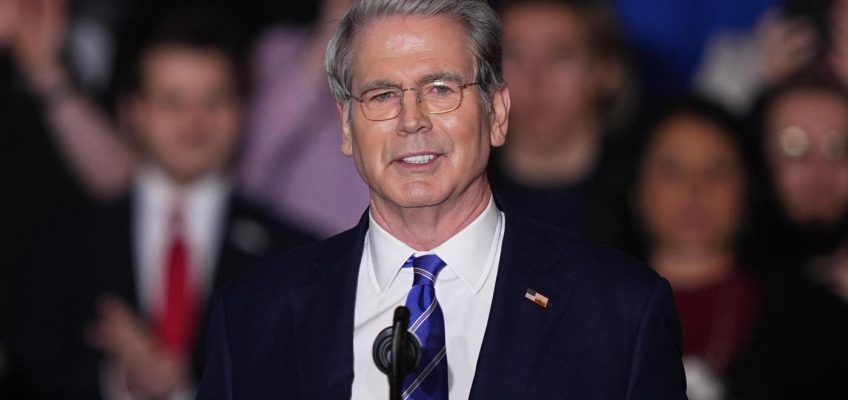

Lawmakers aligned with the ruling party, including Maduro’s son, gathered in the capital, Caracas, to follow through with a scheduled swearing-in ceremony of the National Assembly for a term that will last until 2031. They reelected their longtime speaker — the brother of the newly named interim president, Delcy Rodríguez — and gave speeches focused on condemning Maduro’s capture Saturday by U.S. forces.

“If we normalize the kidnapping of a head of state, no country is safe. Today, it’s Venezuela. Tomorrow, it could be any nation that refuses to submit,” Maduro’s son, Nicolás Maduro Guerra, said at the legislative palace in his first public appearance since Saturday. “This is not a regional problem. It is a direct threat to global political stability.”

Maduro Guerra, also known as “Nicolasito,” demanded that his father and stepmother, Cilia Flores, be returned to the South American country and called on international support. Maduro Guerra, the deposed leader’s only son, also denounced being named as a co-conspirator in the federal indictment charging his father and Flores.

FILE – Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, left, and his son Nicolas Maduro Guerra who is running to represent Caracas as a lawmaker for the National Assembly attend a closing campaign rally for the regional election on May 25, in Caracas, Venezuela, May 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos, File)

While Venezuelan lawmakers met, Maduro made his first court appearance in a U.S. courtroom on the narco-terrorism charges the Trump administration used to justify capturing him and taking him to New York. Maduro declared himself “innocent” and a “decent man” as he pleaded not guilty to federal drug-trafficking charges.

The U.S. seized Maduro and Flores in a military operation Saturday, capturing them in their home on a military base. President Donald Trump said the U.S. would “run” Venezuela temporarily, but Secretary of State Marco Rubio said Sunday that it would not govern the country day-to-day other than enforcing an existing ” oil quarantine.”

Rubio said the U.S. was using pressure on Venezuela’s oil industry as a way to push for policy changes. “We expect to see that there will be changes, not just in the way the oil industry is run for the benefit of the people, but also so that they stop the drug trafficking,” Rubio said on CBS’ “Face the Nation.”

Pro-government armed civilians attend a protest demanding the release of President Nicolas Maduro and first lady Cilia Flores, the day after U.S. forces captured and flew them to the United States, in Caracas, Venezuela, Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

On Sunday, Rodríguez said Venezuela is seeking “respectful relations” with the U.S., a shift from a more defiant tone she struck in the immediate aftermath of Maduro’s capture.

“We invite the US government to collaborate with us on an agenda of cooperation oriented towards shared development within the framework of international law to strengthen lasting community coexistence,” Rodríguez said in a statement. Her conciliatory message came after Trump threatened that she could “pay a very big price” if she did not fall in line with U.S. demands.

US-based multinational companies will be exempt from global tax deal

Finland’s battle against fake news starts in preschool classrooms

US allies and adversaries use UN meeting to blast Venezuela intervention as America defends action

US expands list of countries whose citizens must pay up to $15,000 bonds to apply for visas

A Paris court finds 10 people guilty of cyberbullying France’s first lady Brigitte Macron

Before taking the oath of office, Venezuelan lawmaker Grecia Colmenares said she would “take every giant step to bring back (to Venezuela) the bravest of the brave, Nicolás Maduro Moreno, and our first lady, Cilia Flores.”

“I swear by the shared destiny we deserve,” she said.

A State Department official said Monday that the Trump administration is making preliminary plans to reopen the U.S. embassy in Venezuela.

The official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss internal administration deliberations, said early preparations “to allow for a reopening” of the embassy in Caracas had begun in the event Trump decides to return American diplomats to the country.

Associated Press Writer Matthew Lee in Washington contributed to this report.