Alligator Alcatraz has triggered pride in the MAGA world — and fury in an unlikely bipartisan mix of South Floridians.

In fact, the land where Gov. Ron DeSantis’ administration quickly erected the new immigrant detention center, which is expected to eventually hold 3,000 or more people, has been deeply controversial since the 1960s.

It was supposed to be the planet’s largest jetport and inspire a new city in the middle of the Everglades.

Bipartisan outrage over those dreams (or nightmares) united an odd cross section of Floridians: birder watchers, hunters, native tribes, blue-collar plumbers and Republican advisers.

This David-and-Goliath battle pitted them against heavy hitters: the Dade County Port Authority, the Federal Aviation Administration, the state of Florida, the air transport industry and eager chambers of commerce.

The ensuing fight over the jetport, which eventually drew in then-President Richard Nixon’s administration, was the catalyst for creating Big Cypress National Preserve, and helped shape the environmental movement we know today.

And the bipartisan outrage of the 1960s echoes through today’s protests about that same piece of land.

Heady times and jetport dreams

The 1960s were heady times for Florida. The population jumped by 40%, ramping from about five million in 1960 to nearly seven million by 1970.

As the population (and real estate values) boomed, the Dade County Port Authority started buying up 39 square miles of cypress swamp and Miccosukee ceremonial sites that sat a few miles from both Everglades National Park and Miccosukee tribal land.

They had a dream of building the world’s largest jetport. It would be five times the size of JFK International Airport, big enough to welcome 50 million passengers and one million flights a year, and would serve both the east and west coasts of the state.

The Port Authority had “Jetsons”-esque ambitions — South Florida was poised for global greatness, and the Everglades were in the way.

They claimed Miami’s existing airport would reach capacity by 1973: South Florida needed the jetport!

According to the National Park Service, the plan called for a corridor three football fields wide to span across the Everglades from Miami to the jetport, and then on through the Big Cypress Swamp to the west coast. There’d be both an interstate highway and a train shuttle ripping through at 200 mph.

The maximalist vision of the jetport supporters was that Miami would sprawl 40 miles out into the Everglades and eventually envelop the jetport.

Historian Jack Davis, of the University of Florida, has devoted his studies to the state’s history. He wrote extensively about the battle over the jetport in his 2009 Marjory Stoneman Douglas biography, “An Everglades Providence: Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the American Environmental Century.”

Davis writes that Port Authority director Alan Stewart “envisioned an industrial center congealing around the jetport and the city of Miami expanding toward it. … A new city is going to rise up in the middle of Florida, whether you like it or not.”

The assumption was that development, by definition, brought benefits to the region.

The benefits of saving the only Everglades in the world, and the region’s water supply, were not part of the equation. What harm could come from jet fuel?

Photographed from the eastern edge of Big Cypress Preserve, looking west toward the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport a few miles away on Tamiami Trail E, Ochopee, on Tuesday, June 24, 2025. (Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

‘We thought it was a done deal’

According to Davis, the Port Authority and Federal Aviation Administration did not consult with the national park when selecting the site for the jetport, even though the jetport was upstream from the park and would either flow pollution in or dry it out.

A reporter turned president of the local chapter of the Audubon Society, the late Joe Browder, had the reputation of being a “tenacious bulldog” and a “brash militant.” Those tendencies would come in handy during the impending fight, in which he would pull together an oddball team of conservationists and change the fate of South Florida.

The jetport broke ground in 1968. Much like the DeSantis administration’s rapid-fire build-out of Alligator Alcatraz, which relied on emergency declarations, the Port Authority’s strategy was to build as quickly as possible.

“DeSantis’ position is that illegal immigration is an emergency. … One might say it stretches the definition of an emergency,” said Aubrey Jewett, professor of political science at the University of Central Florida. “An emergency is something that happens very quickly and requires an immediate response.”

Jewett uses the 1980 Mariel boatlift as an example of something that was an immigration emergency. “With little notice, Fidel Castro allowed Cubans to leave the island, and it happened in a brief window of time, and involved hundreds of thousands of people coming to one area — Miami. Literally local communities were overwhelmed.”

“You know, it was just like the Alligator Alcatraz thing — the public didn’t know about the jetport, and the Port Authority was quietly buying up all that land behind the scenes, and we were caught off guard,” said Franklin Adams, who was a crucial part of the jetport battle.

The new migrant detention facility, Alligator Alcatraz, is located at Dade-Collier Training and Transition facility in the Florida Everglades, shown July 4, 2025, in Ochopee, Fla. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

He was in his 20s in the late 1960s when he joined Browder in the fight as a member of the sportsman’s group the Izaak Walton League. He fell in love with Florida wilderness while tagging along as a teen with his father, a land surveyor. “I started seeing some of these incredible places that he surveyed get destroyed, diked. With us going out and roaming the Big Cypress and Everglades, we saw beautiful tree islands inundated and destroyed.”

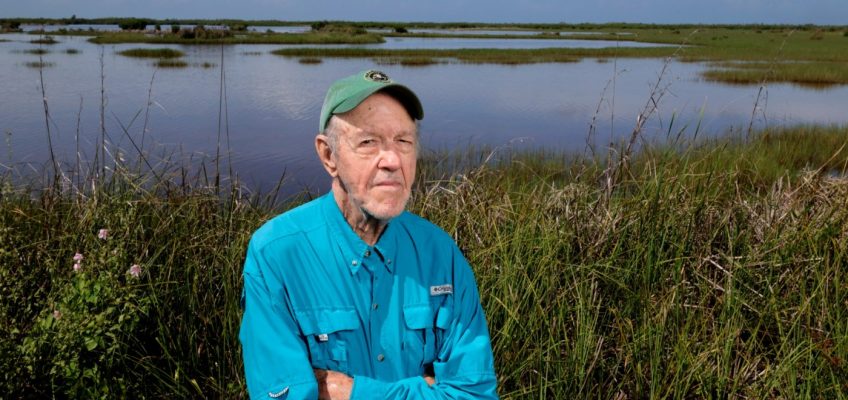

By the time Browder, Adams and other conservationists became organized, some of the runways were already built, and real estate signs started popping up. “We thought it was a done deal,” Adams said. Adams is now 87 and lives in a rural area not far from Big Cypress National Preserve.

As the bulldozers were prepping the swamp for pending runways, Adams and friend Charles Garrett managed to get a meeting with one of the heavy hitters: Port Authority deputy chief Richard Judy. Adams and Garrett implored Judy to reconsider the jetport location. “It was in the watershed of Everglades National Park, (I explained) all the problems it would cause.”

The meeting did not last long. Judy listened briefly, then abruptly ended the meeting, saying that the men had wasted their time and his, Adams recalled. “Well, after that happened, it made us more determined than ever to fight that thing and stop it,” Adams said.

Once the cat was out of the bag, developers on both coasts grew frothy at the mouth. An advertisement of the day read, “Mammoth jetport to whisk community into the future: The future development of Marco Island received a tremendous boost recently with the start of construction of a mammoth jetport, the biggest ever, anywhere just 48 miles away.”

The Collier family and the JC Turner Lumber Company owned much of the land in Big Cypress swamp, and started selling it off at $10 an acre. “People were buying it from all over the world,” Adams said.

According to the Florida National Park Association, real estate billboards were popping up all along the Tamiami Trail at the time the airport was planned. “$10.00 down, $10.00 a month, buy land, get rich,” one read.

“Airport in Glades Could Bring in $$” read a 1967 Miami Herald headline. A local politician at the time predicted it would be the most important airport in the region by 1990.

The entrance sign to Big Cypress National Preserve on Tuesday, June 24, 2025. (Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

An unlikely coalition

Browder knew the local Audubon Society couldn’t take this fight on alone. He would need to build a coalition.

Florida Gov. Claude Kirk had shoveled dirt at the jetport groundbreaking with a grin on his face, but his special assistant on the environment, Republican Nathaniel Reed, was troubled by what he considered runaway development in Florida.

Reed grew up exploring and fishing around Jupiter Island. He was disgusted by the slash-and-burn development mentality in Florida, and felt that the “Great God of Growth” was decimating his state. Reed imagined what the land he loved would look like if the jetport dreams came true, and took a stance against it. He had the governor’s ear, as well as some in Washington, D.C.

Browder also connected with famed environmentalist Marjory Stoneman Douglas, who then founded the nonprofit Friends of the Everglades in order to fight the jetport.

Browder pulled in other potential allies as well. “Astute in ways other environmentalists were not, he recognized that environmental concerns were not the sole province of the middle class or the social elite,” wrote Davis in his book. Browder set up meetings with those who actually used Big Cypress Swamp — hunters and gladesmen, and Native American tribes.

Browder met with Buffalo Tiger, leader of the Miccosukee Tribe of Florida. According to Davis, the Port Authority had told Tiger that the jetport would be environmentally benign and would not damage their way of life. Besides, any development would bring jobs to the tribe.

But Tiger was skeptical. “It happens to Indians year after year: Progress wasting the hunting grounds,” Tiger told a New York Times reporter at the time.

His skepticism was warranted. At some point during the build, construction equipment had leveled the ceremonial site of the Miccosukee’s Green Corn dance, where every new year, the tribe inducted boys into manhood in a ceremony.

There was one glaring problem with what Browder was bringing to the tribes and the closely linked hunters and gladesmen. The jetport fight was explicitly tied to the protection of Big Cypress Swamp by making it a national park.

But most of the coalition hated the idea. Many felt abused by the creation of Everglades National Park in 1947, which had displaced a fishing village in Flamingo, at the southern tip of the park, and had caused resentment among the Miccosukee, some of whom lived south of Tamiami Trail, in what would become the park.

A national park also would mean the end of hunting and private property in Big Cypress. “These people were from old, old families, some of them going back to the 1860s after the Civil War, when they came down to this country,” Adams said. “They said, ‘You know, we’ve got our family cabins, retreats on the Big Cypress now, and if it becomes a national park, we’re going to lose all those.”

The parties came up with a solution; Big Cypress could be a preserve, not a national park. A preserve — the first ever in the U.S. — meant hunters could still hunt, swamp buggies could still roll through the sawgrass prairies and airboats could still zip over sawgrass.

Those with hunting camps could keep them. It also meant its mineral rights could still be sold by the Collier family, which is why there are several active oil rigs in the preserve.

“Nat Reed and Joe Browder got with them,” said Adams, with Browder arguing that if you don’t push back on the jetport, “there’ll be a Kmart out there where you park your swamp buggy. You’re going to lose one way or the other.”

But they needed a guarantee that they’d be able to keep their hunting camps and the right to hunt and use swamp buggies and air boats. They got it, and eventually began to see the light, said Adams.

Not everyone was on board. Adams said advocates for Big Cypress National Preserve had their tires slashed, and he and a friend had to sneak out the back door of a bar near Everglades City when a pack of locals threatened them.

Johnny Jones, a plumber and hunter from Hialeah, would become a cultural connector and savvy teammate. He led the 50,000-member Florida Wildlife Federation, which was filled with hunters. Airboat and swamp buggy groups also joined in. A jetport alone might not ruin their hunting grounds, but the ensuing development would end the world they loved so much.

“Like many of us, he started seeing a lot of these special places ditched and diked and drained by the Army Corps of Engineers, the water management districts, so he got involved,” Adams said.

Jones’ involvement, his connections in Tallahassee and his ability to cajole, became invaluable, Adams said. “Big Cypress and stopping the jetport wouldn’t have happened if they hadn’t come around.”

Beers, gators and an unexpected friend

Even with Reed at the governor’s ear, it became clear that to overcome the Goliaths, Browder, Reed, Adams and Jones would need friends in higher places than Miami or Tallahassee. Alligators, fittingly, were the conduit.

Florida outlawed alligator hunting in 1962, but poaching was still a livelihood in the swamps. Enforcement was tough. The plight of the reptiles garnered national attention, and when the Nixon administration put their finger to the wind of public opinion, it caught their attention, too.

The new interior secretary, an Alaskan car dealer named Walter Hickel, made an “on-the-spot investigation” into poaching a priority.

While on his Florida adventure in 1969, Hickel voyaged deep into the Ten Thousand Islands section of Everglades National Park with Gov. Kirk and others, and played “poacher” as rangers chased him by boat through the mangroves. Amid the camaraderie, Hickel promised to beef up alligator protection, and he and Kirk talked about the jetport.

In spring of 1969, Hickel was “determined not to lose a park to the roughshod behavior of another agency or department, local or federal, and they had powerful allies in Congress,” wrote Davis.

The Senate held hearings to reconcile the jetport conflict, and commissioned a study on how the jetport would impact Everglades National Park, which was downstream. Environmental impact studies are normal today, but it was a relatively new concept at the time.

At the June 1969 hearings on Capitol Hill, the study stated, “Development of the proposed jetport and its attendant facilities will lead to land drainage and development for agriculture, transportation, and services in the Big Cypress Swamp, which will inexorably destroy the south Florida ecosystem and thus the Everglades National Park.”

Boom. Committee members came out against the jetport, with scientific backing for their stance.

“Once that report came out … I think that was the major turning point,” Adams said. “Because that was pure science, peer-reviewed. It was irrefutable, and that’s when the Port Authority got nervous.”

Davis wrote that the deputy director of the Port Authority, Richard Judy, was defiant, though, stating that regardless of what the study reported, “We’re going to build the jetport.”

But then Gov. Kirk, relying heavily on Reed’s advice, decided against the jetport as well, recommending an alternative site in Palm Beach County. With nowhere to turn, the Port Authority relented.

Two years later, Big Cypress National Preserve was established and the larger Everglades system as we know it today was protected.

This was a period where the U.S. was essentially inventing environmental regulation as we know it. President Nixon, as ethically challenged as he was, signed the Endangered Species Act into law on Dec. 28, 1973. The jetport study became a model for federal requirements, according to Davis, and the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency started enforcing the equally new Clean Air Act.

“That was kind of the tail end of the development-at-any-cost mentality in Florida, coming off the post-war boom and the invention of air conditioning,” Jewett said.

“Much of the environmental protection of America came about in the 1960s and ’70s,” Jewett said. “It wasn’t easy. We had pitched political battles.”

The fight over the jetport was one of those battles, and it drastically altered what South Florida looks like today.

The fight today

While recently visiting the detention site, President Donald Trump raved about Alligator Alcatraz. Wilton Simpson, Florida’s agriculture commissioner, accompanied Trump on the tour and lavished him with praise, stating, “We are grateful for your leadership. … God had a plan for us, and it was Donald Trump.”

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem has advised other states to follow Florida’s model. And the Florida GOP is so pleased with the site that they’ve got “Alligator Alcatraz” merchandise for sale online.

President Donald Trump speaks with reporters as he tours Alligator Alcatraz, a new migrant detention facility at Dade-Collier Training and Transition facility, on July 1, 2025, in Ochopee, Fla. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

DeSantis has painted protests over Alligator Alcatraz as partisan nonsense, dismissing environmental concerns by saying there will be “zero” impact, and implying that those opposed are merely left-wingers using the Everglades “as a pretext just for the fact that they oppose immigration enforcement.”

Outdoorsman Mike Elfenbein would beg to differ. He’s the executive director for the Cypress Chapter of the Izaak Walton League and has been hunting deer and turkey, fishing, off-roading and camping in the Big Cypress for most of his life. He praised both Trump and DeSantis for their work on Everglades restoration, which is why the detention center makes no sense to him.

“I think it’s in a really bad place (for the detention center),” he said. “The Cypress chapter of the Izaak Walton League was created with the express purpose of advocating for the creation of Big Cypress National Preserve and not developing the jetport.

“The agreement back then in the ’70s was that that land was not going to be used or impacted beyond what had already happened, and it would be open for recreational use and for its ecological value … forever. This is contrary to that agreement.” Elfenbein said the center needs to be in a different place, and suggested Homestead Air Reserve Base.

“Alligator” Ron Bergeron, the colorful conservationist who sits on the board of the South Florida Water Management District and who once considered running for governor as a Republican, is also against the detention center.

His foundation released a statement that looked back to the jetport fight. “Our founder, Alligator Ron Bergeron, was one of the original Gladesmen in the 1970s who joined with Tribal leaders, conservationists, hunters, anglers, and scientists to fight the original jetport proposal and protect this sacred landscape.”

The Bergeron statement suggested alternative sites such as Camp Blanding or the Homestead Air Reserve Base. “These locations offer existing infrastructure, greater security, and far less ecological risk. Unlike the proposed site, these alternatives would not threaten imperiled wildlife … or directly impact the Miccosukee Tribe, who live on this land and depend on its health for their way of life.”

Protesters converge outside the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport on Tamiami Trail E, Ochopee, on July 1, 2025, site of the new immigration detention center, Alligator Alcatraz. (Joe Cavaretta/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Elfenbein attended the first protest of the then-pending detention center. “There were all kinds of people there; there were hunters, there were sportsmen, there were MAGA guys, there were, you know, ultra-liberal folks. There was every walk of life.”

He said the upset over the detention center is much like what happened in the late ’60s and early ’70s. “People from all walks of life, from all political persuasions and cultural lineage and race and creed or color, everybody agreed on one thing, that this place was too important to destroy. … This (detention center) is the opposite of that.”

As for DeSantis’ idea that those opposed to the center are merely opposed to immigration enforcement, “I don’t agree with that,” Elfenbein said. “I would tell you this is not a left-wing or a right-wing (issue). This is every wing.”

On June 27, environmental groups, including Friends of the Everglades, the nonprofit founded by Marjory Stoneman Douglas during the fight to stop the original jetport, filed a federal lawsuit to halt activity at the site to allow time for an environmental impact study, something required by federal law.

“Lawsuits could slow it down or stop it,” said Jewett. “Whether they will is another story. It depends on which court it goes to. On the state level it seems unlikely. Ideologically they lean to DeSantis.”

Then there’s public opinion. “Public opinion is something that politicians still care about. If there was a big uprising in public opinion and it became more clear that a strong majority of Floridians, including a healthy percentage of Republicans, were against this, then maybe it would be rethought.”

Jewett said one example was the “state park fiasco” of 2025, in which a plan, backed by the DeSantis administration, to build golf courses and large hotels in state parks was leaked to the news media. Social media drove a bipartisan resistance so vocal that the plan blew up in the DeSantis administration’s face, and a bill, signed by DeSantis in May, was passed to make such developments illegal in state parks.

“Alligator Alcatraz is a travesty,” Adams said. “It’s going to do damage — if we have a major hurricane this summer, that thing is not going to stand there and all, with the sewage and chemicals. And they’re going to have to spray for mosquitoes, which is not allowed in the Big Cypress or the National Park.” (State officials have said structures at Alligator Alcatraz can withstand a hurricane of up to Category 2, and if an approaching storm were stronger, then the site would be evacuated.)

Davis’ research revealed that in a 1970 New York Times article about the end of the jetport saga, Buffalo Tiger said, “You can’t make it. You can’t buy it. And when it’s gone, it’s gone forever.”

Adams said he knows younger conservationists who are despondent over the current state of environmental fights: The Trump administration recently declared that the new purpose of the Environmental Protection Agency is to “lower the cost of buying a car, heating a home and running a business.” And the administration has worked to weaken the Clean Water Act and neuter the habitat protection powers of the Endangered Species Act.

Adams said his experience with the jetport taught him lessons. “Don’t let go,” he said. “Don’t stop. What’s worse, picking up the morning paper and seeing what the bastards are doing, and just complaining and bitching about it? Or getting involved? If we don’t, we’ll be overrun.”

Bill Kearney covers the environment, the outdoors and tropical weather. He can be reached at bkearney@sunsentinel.com. Follow him on Instagram @billkearney or on X @billkearney6.