Solo este año, miles de neoyorquinos con bajos ingresos han sufrido el robo de los fondos de sus tarjetas EBT, que les permiten comprar alimentos en ciertas tiendas. “Fue muy duro”, declaró una víctima a City Limits después de que le vaciaran su cuenta SNAP en tres ocasiones distintas.

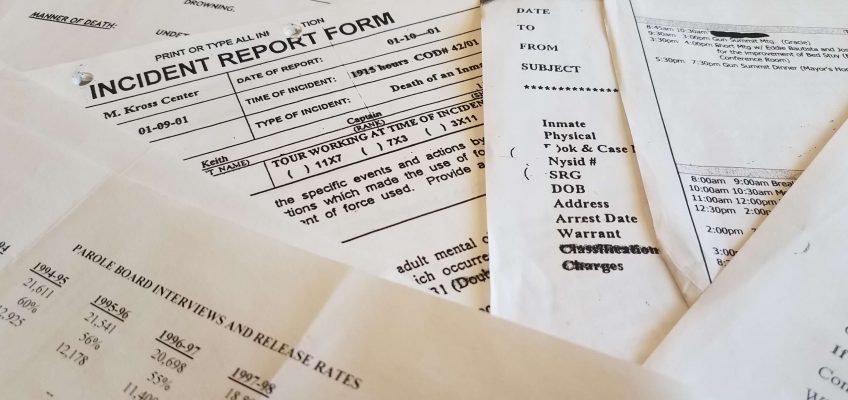

Un cartel de EBT en una tienda en East Gun Hill Road, en el Bronx. (Adi Talwar/City Limits)

Este artículo se publicó originalmente en inglés el 16 de octubre. Traducido por Daniel Parra. Read the English version here.

En solo un año, Theresa Price, residente de Woodside Houses de NYCHA, ha sufrido tres robos del dinero de la ayuda alimentaria del Programa Federal de Asistencia Nutricional Suplementaria (SNAP por sus siglas en inglés, y también conocido como cupones de alimentos).

Cada vez que ocurría, eran $292 dólares menos para comer ese mes.

Cada vez, debía pedir dinero prestado para cubrir lo que le habían quitado.

Dos de los robos ocurrieron en abril y septiembre, después de que expirara el período de reembolso del gobierno federal a finales del año pasado, lo que significaba que lo robado no sería reemplazado.

“Te decían que fueras a la despensa [de alimentos]”, recuerda Price que le dijo el personal de la Administración de Recursos Humanos (HRA por sus siglas en inglés) de la ciudad después de que denunciara el incidente. “Fue duro. Fue muy duro”.

Price, de 61 años, es una de las decenas de miles de personas a las que les han robado dinero de sus tarjetas de transferencia electrónica de beneficios (EBT por sus siglas en inglés) en el estado de Nueva York este año.

Ella y otras víctimas se han quedado sin ningún recurso: el gobierno federal dejó de aceptar solicitudes de reembolso a finales de septiembre y solo para los robos que tuvieron lugar antes del 21 de diciembre de 2024. Los congresistas no renovaron la ayuda para sustitución.

Nueva York ha sido un nido del llamado “skimming”, en el que dispositivos ocultos roban la información de pago después de que alguien pase su tarjeta. Según la Oficina de Asistencia Temporal y por Discapacidad (OTDA por sus siglas en inglés) del estado, que administra el SNAP en Nueva York, se pagaron $51.8 millones de dólares en reembolsos entre el 23 de agosto de 2023 y el 30 de junio de 2025.

Solo en los primeros seis meses de este año, del 1 de enero al 30 de junio, los neoyorquinos denunciaron un total de $14.5 millones de dólares en beneficios de SNAP robados en todo el estado, según informaron funcionarios de la OTDA a City Limits.

“La OTDA se toma muy en serio cualquier denuncia de robo de prestaciones y mantiene su compromiso de proteger las prestaciones de los neoyorquinos frente a los estafadores. Se insta a los usuarios de EBT a que sean conscientes del fraude por skimming y estén revisando sus prestaciones”, afirmó un portavoz de la OTDA en un comunicado.

Aunque el programa SNAP está financiado por el gobierno federal para ayudar a los hogares con bajos ingresos a pagar los alimentos, son los estados los que se encargan de su gestión. En Nueva York, la OTDA lo supervisa, mientras que la HRA opera y gestiona el programa en la ciudad.

El Departamento de Agricultura de los Estados Unidos, responsable del SNAP a nivel federal, no respondió a las preguntas sobre el impacto de los robos y su oficina de prensa afirmó por correo electrónico que no podía responder inmediatamente a las preguntas de los medios de comunicación debido al cierre del gobierno.

Según la HRA, que forma parte del Departamento de Servicios Sociales (DSS por sus siglas en inglés) de la ciudad de Nueva York, hasta septiembre los residentes de la ciudad de Nueva York habían presentado más de 34.000 reclamaciones de robos por skimming de tarjetas EBT.

El DSS también afirmó que, tras finalizar el periodo de reembolso federal, menos personas han presentado reclamaciones porque sabían que sus prestaciones no serían sustituidas, lo que dificulta determinar el alcance total del problema.

En abril, por ejemplo, después de que le robaran los fondos por segunda vez, Price no volvió a la oficina de la HRA para denunciar. Tampoco presentó ninguna denuncia ante la policía cuando le robaron las prestaciones por tercera vez en septiembre.

“Grité. Grité de verdad”, dijo sobre el tercer robo. “No fui a la comisaría ni nada, porque era una pérdida de tiempo”.

Desde el 2023, los legisladores estatales han presentado proyectos de ley que obligarían a Nueva York a actualizar las tarjetas EBT con chip de seguridad, pero la legislación aún no se ha aprobado. Otros estados, como California y Oklahoma, ya han realizado la transición a tarjetas más seguras.

En julio, Legal Services NYC presentó una demanda exigiendo al estado que cambiara a una tecnología de tarjetas más segura y que elaborara un plan para reemplazar los beneficios del SNAP que se pierden por el skimming hasta que se disponga de tarjetas más seguras.

Días más tarde, la OTDA publicó una convocatoria de propuestas para buscar un proveedor que suministrara una tarjeta de identificación de varias prestaciones, que permitiría a los neoyorquinos acceder a diversas prestaciones gubernamentales, como SNAP, Asistencia Temporal para Familias Necesitadas, Medicaid y subsidios de EBT de verano para alimentos.

El 7 de octubre, decenas de organizaciones de Nueva York, entre ellas defensores de la lucha contra el hambre, enviaron una carta a la gobernadora Kathy Hochul instando al estado a asignar fondos, tanto para actualizar las tarjetas de prestaciones con banda magnética actuales con tecnología de chip cifrada más segura, como para reemplazar las prestaciones robadas a los afectados después de la fecha límite de 2024.

“El skimming agrava la inseguridad alimentaria y el estrés financiero de los hogares ya vulnerables, lo que les dificulta satisfacer sus necesidades básicas y mantener la estabilidad”, dice la carta. “Hemos escuchado innumerables historias desgarradoras e inaceptables de familias que han tenido que saltarse comidas o devolver los alimentos a las estanterías después de descubrir en la caja registradora que les habían robado sus prestaciones alimentarias”.

Una mujer que habló con City Limits, y quien pidió permanecer anónima, dijo que su familia tuvo que retrasar el pago del alquiler después de que les robaran el dinero de la tarjeta EBT durante el verano. “Tuvimos que atrasarnos en la renta para poder comprar comida”, dijo ella, de 31 años, madre de un bebé de un año.

Para compensar los fondos robados, su marido, que trabaja en un restaurante, vendió flores cerca de su casa en el sur del Bronx después de su turno durante un par de semanas.

Una tienda en la calle East 204th Street, en el Bronx. (Adi Talwar/City Limits)

No es 100 por ciento eficaz

Tres personas afectadas por el robo de fondos que hablaron con City Limits sobre sus experiencias dijeron que habían tomado precauciones para evitar el skimming. Habían descargado la aplicación móvil ebtEDGE, que les permite “congelar” la tarjeta cuando no la utilizan. Dos de ellas también habían desactivado las transacciones fuera del estado.

Susan Kingsland, subdirectora de servicios sociales de Red de Pueblos Transnacionales (una organización comunitaria que es parte de la demanda de Legal Services NYC), dijo que es frustrante impartir talleres para enseñar a sus clientes cómo usar las tarjetas EBT de forma segura, para luego seguir viendo cómo roban a la gente.

“Lo que también es muy importante es [que] hay algunas medidas que se pueden tomar para prevenirlo, pero nunca hay una garantía del 100 por ciento”, dijo Kingsland.

Los funcionarios del DSS reconocieron que esta es la razón principal por la que abogan por el cambio a tarjetas con tecnología con chip.

Aunque no es infalible, los funcionarios y defensores recomendaron lo siguiente:

Utilice la función de bloqueo de la tarjeta EBT en la aplicación ebtEDGE (disponible en Apple App Store y Google Play Store) o en el sitio web de ebtEDGE. Desbloquee la tarjeta solo justo antes de realizar una compra y bloquéela inmediatamente después para evitar nuevas transacciones.

Cambie el PIN con frecuencia y no lo comparta con nadie.

Realice un seguimiento de su cuenta EBT y sus transacciones.

Evite hacer clic en enlaces desconocidos en correos electrónicos o mensajes de texto para no caer en el llamado “phishing”.

Cuando pague en una caja registradora, revise y sacuda un poco el lector de tarjetas, ya que los dispositivos de skimming a veces están mal fijados a los teclados o lectores de tarjetas. “Esté atento a cualquier irregularidad en el lector de tarjetas de los comercios, y sus teclados, antes de utilizarlos”, aconseja un portavoz de la OTDA.

Si encuentra un dispositivo de skimming, llame a la Unidad de Fraude de la HRA al 718-557-1399.

Si me roban mis fondos en la tarjeta EBT, ¿qué debo hacer?

Si utiliza la aplicación ebtEDGE, bloquee la tarjeta inmediatamente. Denúncielo de inmediato y solicite una nueva tarjeta en una oficina de la HRA o en www.ebtEDGE.com, en la aplicación ebtEDGE o por teléfono a través de la línea de atención al cliente de EBT al 1-888-328-6399.

Aquellos que han logrado robar fondos de una tarjeta pueden volver a hacerlo de la misma tarjeta, por lo que se recomienda solicitar una nueva.

Para ponerse en contacto con el reportero de esta noticia, escriba a Daniel@citylimits.org. Para ponerse en contacto con la editora, escriba a Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.

The post Más de $14 millones de dólares en beneficios de SNAP han sido robados de neoyorquinos tras el fin del programa de reembolso appeared first on City Limits.