Today is Friday, Feb. 20, the 51st day of 2026. There are 314 days left in the year.

Today in history:

On Feb. 20, 1939, more than 20,000 people attended a rally held by the German American Bund, a pro-Nazi organization, at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

Also on this date:

In 1792, President George Washington signed an act creating the United States Post Office Department, the predecessor of the U.S. Postal Service.

Related Articles

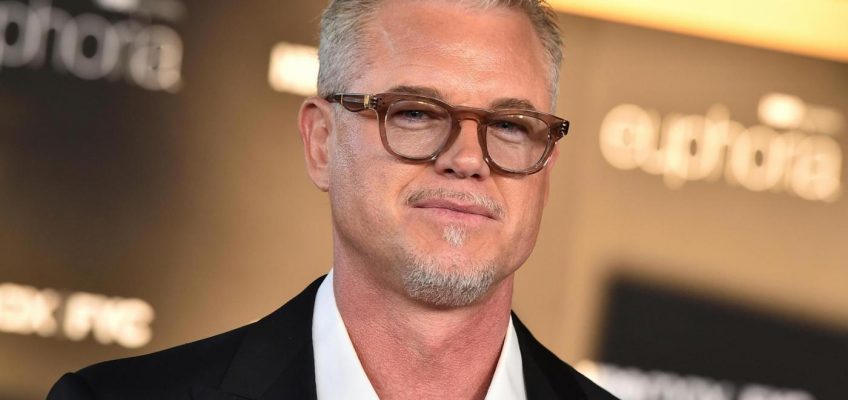

Eric Dane, ‘Grey’s Anatomy’ star and ALS awareness advocate, dies at 53

Prosecutors stand by former Black Panther’s conviction but accuse judge of misconduct when he prosecuted the case

Judge orders takeover of health care operations in Arizona prisons after years of poor care

NASA boss blasts Boeing and space agency managers for Starliner’s botched astronaut flight

Memorial services for Rev. Jesse Jackson expanded to include South Carolina and Washington, DC

In 1862, William Wallace Lincoln, the 11-year-old son of President Abraham Lincoln and first lady Mary Todd Lincoln, died at the White House from what was believed to be typhoid fever.

In 1905, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, upheld, 7-2, compulsory vaccination laws intended to protect the public’s health.

In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt signed an immigration act which excluded “idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded persons, epileptics, insane persons,” among others, from being admitted to the United States.

In 1962, astronaut John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth, circling the globe three times aboard Project Mercury’s Friendship 7 spacecraft in a flight lasting 4 hours and 55 minutes before splashing down safely in the Atlantic Ocean.

In 1965, America’s Ranger 8 spacecraft crashed into the moon’s surface, as planned, after sending back thousands of pictures of the lunar surface.

In 1998, American Tara Lipinski, age 15, became the youngest-ever Olympic figure skating gold medalist when she won the ladies’ title at the Nagano (NAH’-guh-noh) Olympic Winter Games; American teammate Michelle Kwan took silver.

In 2003, a fire sparked by pyrotechnics broke out during a concert by the rock group Great White at The Station nightclub in West Warwick, Rhode Island, killing 100 people and injuring over 200 others.

In 2016, a Michigan man shot and killed six strangers and wounded two others over several hours in the Kalamazoo area in between picking up passengers for a ride service. (Jason Dalton pleaded guilty in 2019 and was sentenced to life in prison without parole.)

Today’s birthdays:

Racing Hall of Famer Roger Penske is 89.

Hockey Hall of Famer Phil Esposito is 84.

Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky is 84.

Film director Mike Leigh is 83.

Actor Brenda Blethyn is 80.

Actor Sandy Duncan is 80.

Basketball Hall of Famer Charles Barkley is 63.

Model Cindy Crawford is 60.

Actor Andrew Shue is 59.

Actor Lili Taylor is 59.

Singer Brian Littrell (Backstreet Boys) is 51.

Actor Lauren Ambrose is 48.

Actor Jay Hernandez is 48.

MLB pitcher Justin Verlander is 43.

Comedian-TV host Trevor Noah is 42.

Actor Miles Teller is 39.

Singer Rihanna is 38.

Singer-actor Olivia Rodrigo is 23.