By LEANNE ITALIE, Associated Press

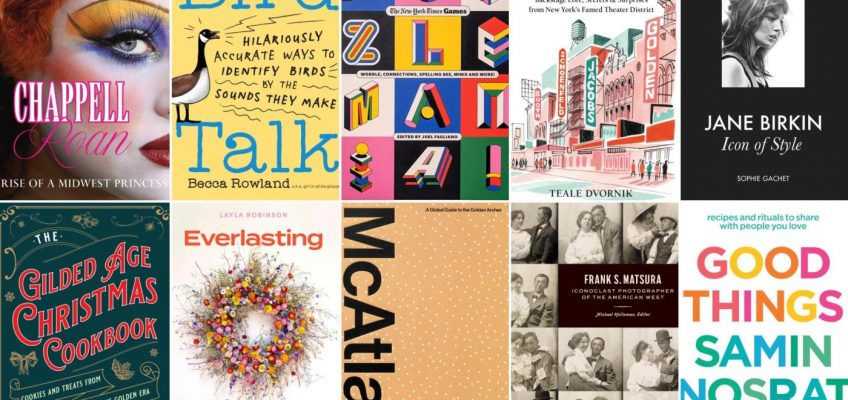

Birding. Photography. The great outdoors. Big Macs.

Chances are good there’s a nonfiction book out there to suit just about anybody on your holiday gift list.

Some ideas:

For your puzzlers

This image shows cover art for “Puzzle Mania!” by The New York Times Games and Joel Fagliano. (Authors Equity via AP)

Imagine, if you will, a world without mobile phones, the internet or The New York Times (digital OR print). Would your favorite puzzler survive? The good folks at the Times have something perfect to put in the bunker: “Puzzle Mania!” It’s a stylish hardcover book full of Wordle, Connections, Spelling Bee, Minis and more. By a lead Times puzzle editor, Joel Fagliano. Authors Equity. $38.

Contemporary art

This cover image released by Monacelli shows the self-titled contemporary art book by Derrick Adams. (Monacelli via AP)

Painting, collage, photography, sculpture, performance. Derrick Adams has embraced them all in a career spanning more than 25 years. His first monograph, “Derrick Adams,” includes 150 works that explore Black American culture and his own identity. Portraiture abounds. There’s joy, leisure and resilience in everyday experiences and self-reflection, with a little humor on board. Monacelli. $79.95.

Steph Curry inspiration

This cover image released by One World shows “Shot Ready” by Stephen Curry. (One World via AP)

“Being shot ready requires practice, training and repetition, but it rewards that work with an unmatched feeling of transcendence.” That’s Golden State Warrior Stephen Curry in his new book, “Shot Ready.” The basketball star takes his readers from rookie to veteran, accompanied by inspiring words and photos. One doesn’t have to be into basketball to feel the greatness. One World. $50.

The American West

This image shows cover art for “Frank S. Matsura: Iconoclast Photographer of the American West.” (Princeton Architectural Press, an imprint of Chronicle Books via AP)

The photographer Frank S. Matsura died in 1913, but his work lives on in a hefty archive. He was a Japanese immigrant who chronicled life in Alaska and the Okanogan region of Washington state. He operated a photo studio frequented by the Indigenous people of the region. Many of those portraits are included in “Frank S. Matsura: Iconoclast Photographer of the American West.” Edited by Michael Holloman. Princeton Architectural Press. $40.

The gift of bird chatter

This cover image released by Storey Publishing shows “Bird Talk: Hilariously Accurate Ways to Identify Birds by the Sounds They Make” by Becca Rowland. (Storey Publishing via AP)

Cheeseburger, cheeseburger! The handy little book “Bird Talk” seeks to make identifying bird calls fun and accessible without heavy phonetic descriptors or birder lingo. Becca Rowland, who wrote and illustrated, offers funny, bite-size ways to identify calls using what’s already in our brains. Hence, the black-capped chickadee goes “cheeseburger, cheeseburger!” Storey Publishing. $16.99.

Mocktails and cocktails

This cover image released by Plume shows “Both Sides of the Glass: Paired Cocktails and Mocktails to Toast Any Taste” by Neil Patrick Harris and David Burtka. (Plume via AP)

David Burtka is sober. His husband, Neil Patrick Harris, imbibes. Together, they love to throw parties. This elfin book, “Both Sides of the Glass,” includes easy-to-follow cocktail and mocktail recipes, with commentary from Harris, who took mixology lessons out of sheer love of a good drink. Written with Zoë Chapin. Plume. $35.

It’s a book. It’s a burger.

This cover image shows “McAtlas: A Global Guide to the Golden Arches” by Gary He. (Gary He via AP)

This tome with a cover design that evokes a Big Mac is a country-by-country work of journalism that earned two 2025 James Beard awards for Gary He, a writer and photographer who previously freelanced for The Associated Press and self-published the book. He toured the world visiting McDonald’s restaurants to do his research for “McAtlas: A Global Guide to the Golden Arches.” As social anthropology goes, it serves. $49.95.

Yosemite love

From the cute but ferocious river otter to the gliders of the night, the Humboldt’s flying squirrel, this striking book is the first comprehensive work in more than a century dedicated entirely to the park’s animal kingdom. “Yosemite Wildlife: The Wonder of Animal Life in California’s Sierra Nevada” includes more than 300 photos and covers 150-plus species. By Beth Pratt, with photos by Robb Hirsch. Yosemite Conservancy. $60.

Samin Nosrat’s new book

This book cover image released by Random House shows “Good Things: Recipes and Rituals to Share with People You Love: A Cookbook” by Samin Nosrat. (Random House via AP)

Samin Nosrat lays herself bare in this long-awaited second book from the chef and author of the acclaimed “Salt Fat Acid Heat.” Her first book was 17 years in the making. In its wake, she explains in “Good Things,” was struggle, including overwhelming loss with the deaths of several people close to her and a bout of depression that nearly swallowed her whole. Here, she rediscovers why she, or anybody, cooks in the first place. The recipes are simple, her observations helpful. You can taste the joy in every bite. Penguin Random House. $45.

Chappell Roan

This book cover image released by Hearst Home shows “Chappell Roan: The Rise of a Midwest Princess.” (Hearst Home via AP)

She struggled in the music game for years, until 2024 made her a star. Chappell Roan, with her drag-queen style, big vocals and queer pride, has a shiny Grammy for best new artist. Now, in time for the holidays, there’s a sweet little book that tells her origin story. “Chappell Roan: The Rise of a Midwest Princess.” With text contributions from Jennifer Keishin Armstrong, Dibs Baer, Patrick Crowley, Izzy Grinspan, J’na Jefferson, Ilana Kaplan and Samantha Olson. Hearst Home. $30.

Snoop’s homemade edibles

For edible-loving weed enthusiasts, “Snoop Dogg’s Treats to Eat” offers 55 recipes that can be done with or without the weed. The connoisseur includes tips on how to use your goods for everything from tinctures to gummies, cookies to cannabutter. Perhaps a loaded milkshake or buttermilk pancakes with stoner syrup. Chronicle Books. $27.95.

A style muse

This cover image released by Abrams Books shows “Jane Birkin: Icon of Style” by Sophie Gachet. (Abrams Books via AP)

With her effortless beauty, and tousled hair and fringe, Jane Birkin easily transitioned from her swinging London roots in the early 1960s to a cultural and style muse for decades. She lent a bohemian charm to everything she did, from acting to singing to liberal activism. And she famously was the muse for the Hermès Birkin bag. The new “Jane Birkin: Icon of Style,” encompasses all of Birkin. By Sophie Gachet. Abrams Books. $65.

More Taylor Swift

This book cover image released by Black Dog & Leventhal shows “Taylor Swift All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track” by Damien Somville and Marine Benoit. (Black Dog & Leventhal via AP)

All those Easter eggs. All those songs. It’s Taylor Swift’s world and we’re just eyes and ears taking it all in. Swift has been everywhere of late with her engagement to Travis Kelce, her Eras tour and now, “The Life of a Showgirl.” Add to the pile “Taylor Swift All the Songs,” a guide to the lyrics, genesis, production and secret messages of every single song, excluding “Showgirl” tracks. By Damien Somville and Marine Benoit. Black Dog & Leventhal. $60.

Got a theater buff?

What’s the beating heart of American theater? Broadway, of course. Teale Dvornik, a theater historian known on social media as The Backstage Blonde, has written a handy little history of New York’s Theater District, “History Hiding Around Broadway.” She takes it theater by theater, offering backstage insights into the venues themselves, along with shows that played there and Broadway highlights through the ages. Running Press. $25.

Christmas baking, Gilded-Age style

Sugarplums. They’re a thing! Fans of “The Gilded Age” are well aware and will eat up “The Gilded Age Christmas Cookbook.” It includes treats from the era, some culinary history and a lot of old-time charm. For the record, sugarplums date to the 1600s, when they were basically just sugar. By the Gilded Age, starting roughly in the late 1800s, they were made from chopped dried figs, nuts, powdered sugar and brandy. Yes, please. By Becky Libourel Diamond. Globe Pequot. $34.95.

Forever flowers

This cover image released by Hachette Mobius shows “Everlasting Blooms” by Layla Robinson. (Hachette Mobius via AP)

Know a crafter? Know a flower lover? In “Everlasting Blooms,” floral artist Layla Robinson offers more than 25 projects focused on the use of dried flowers. She includes a festive flower crown, table displays, wreaths and arrangements with buds and branches. Her step-by-step guidance is easy to follow. Robinson also instructs how to forage and how to dry flowers. Hachette Mobius. $35.

Michelle Obama style

This cover image released by Crown Publishing shows “The Look” by Michelle Obama. (Crown Publishing via AP)

A brown polyester dress with a plaid skirt and a Peter Pan collar. That’s the very first fashion statement Michelle Obama can remember making, circa kindergarten. It was up, up and away from there, style-wise. The former first lady is out with a photo-packed book, “The Look,” taking us behind the scenes of her style and beauty choices. Crown. $50.