New York State is still waiting on $400 million from the federal government to open applications for its energy assistance program this winter. In the meantime, officials are urging residents in need to check their eligibility for another state initiative that secures a monthly utility discount for low-income households.

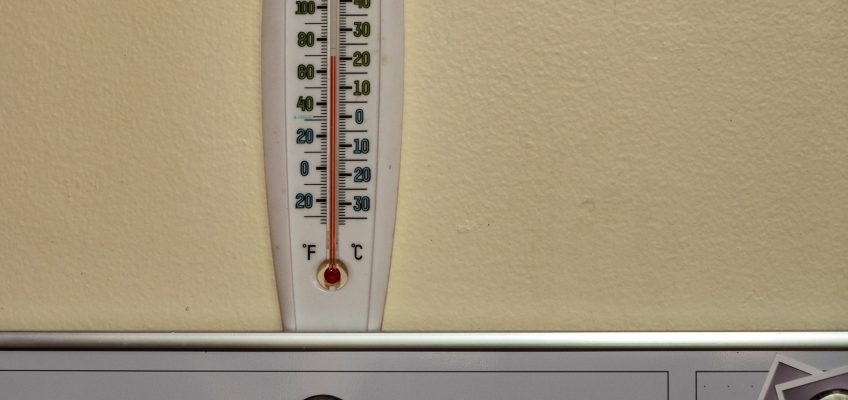

(Adi Talwar/City Limits)

While the federal government has been back open for nearly two weeks, New York State is still waiting on $400 million from the Trump administration to open applications for its home energy assistance program this winter, known as HEAP.

In the meantime, officials are urging residents in need to check their eligibility for another state initiative that secures monthly utility discounts for low-income households.

The New York Energy Assistance Program (EAP) provides the discounts for households that earn below a certain income threshold—what officials say can save participants up to $500 per year.

To be eligible, applicants must prove their participation in one of several public benefit programs, including SNAP, Supplemental Security Income, Medicaid and federal public housing assistance (a full list can be found here). They’re also eligible if they’re enrolled in the Home Energy Assistance Program, or HEAP, which is based on income (a family of four can earn up to $6,680 a month, or $80,165 annually, and qualify).

Beginning in 2026, families can be eligible for EAP even without participating in another benefits program as long as they meet the income requirements, which will also expand next year to those earning up to the Area Median Income for New York City, according to Gov. Kathy Hochul’s office.

Last year, around 1 million households across the state benefited from monthly EAP discounts, but an additional 1.5 million are estimated to be eligible and haven’t applied, according to the governor.

“We’re not leaving people out in the cold and letting bills escalate,” Hochul said during a press conference last week. “I want to urge all eligible households to sign up for the programs we have here in New York.”

Meanwhile, the governor says the state is still waiting on federal funds to open applications for HEAP, which is distinct from EAP and provides direct payments toward participants’ utility bills. The amount varies—maxing out at $996—based on income, household size, heating source, and if the household contains a vulnerable member (a child under 6, adult 60 or older, or residents who are permanently disabled).

Nearly 1 million New York City households received HEAP assistance last winter. It was supposed to open applications for this season on Nov. 3, but enrollment was delayed thanks to the federal government shutdown—and remains on hold despite the government reopening earlier this month.

Hochul says the Trump administration has yet to release the $400 million that funds New York’s HEAP. A spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees the funding, did not return City Limits’ request for comment.

But the federal agency informed states that funding would be dispersed by the end of the month, according to Hochul’s office. If that’s the case, the state expects to open HEAP applications the first week of December.

“Governor Hochul continues to demand the immediate release of these federal funds, while also helping enroll more New Yorkers in state programs for monthly energy discounts and ensuring that vulnerable households don’t lose access to heat,” Spokesperson Ken Lovett said in a statement.

The delay comes as New Yorkers’ utility bills are going up: both National Grid and Con Edison recently approved multi-year rate hikes for customers in the five boroughs.

A report last year from the climate policy think tank Switchbox found that one of every four New York residents is “energy burdened,” meaning they spend at least 6 percent of their income on utility bills. In the Bronx, 34 percent of households are energy burdened, among the highest of any New York county, the report found.

To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.

The post Struggling to Afford Heating Bills? See If You Qualify For This NYS Discount appeared first on City Limits.