PHOENIX — Leaders of the Gophers football program discussed one of the biggest hot-button topics over dinner last week at the luxurious Sheraton Grand Resort at Wild Horse Pass.

Before winning the Rate Bowl, 20-17 over New Mexico on Friday, Athletics Director Mark Coyle, head coach P.J. Fleck and general manager Gerrit Chernoff met to look ahead at the opening of the transfer portal on Friday. It was one of many, many discussions they have had on the issue.

“It comes up on Jan. 2. We all know that date. We all know it’s coming really quickly,” Coyle told the Pioneer Press last week.

The bowl game was the 13th and final data point to conclude the Gophers’ batting average wasn’t high enough on incoming players across last year’s two transfer portal windows.

They finished with an 8-5 record this year, but that mark could have been better if they hit on more than a few new players last winter and spring.

Minnesota, and everyone in the nation, will only have a few, short weeks to improve its roster for next season. With no spring window this year, players have until Jan. 16 to enter the portal, with the goal of them committing, signing contracts and enrolling at their new school in time for spring semester in January.

The Gophers will enter Year 2 of revenue-sharing payments to players in June and will be adjusting how to best use approximately $15 million allocated annually to their football roster. To strategize, the U has consulted with the Timberwolves, Vikings and Wild to learn about how Minnesota’s pro teams manage their salary caps, Coyle said.

“They talked about the importance of (how) you have to have good data, because if you miss on somebody, it’s a kick in the shins,” Coyle said. “That is what we have to evaluate in terms of moving forward, having good evaluations on players.”

For 2025, the Gophers were successful with cornerback John Nestor, receiver Javon Tracy and punter Tom Weston. All three of those starters are back next season, too.

The Gophers also had serviceable additions in right tackle Dylan Ray, defensive tackle Rushawn Lawrence and kicker Brady Denaburg. They were seniors this year.

Minnesota had a bigger handful of players who can be given incomplete grades for their time so far with the program because they have eligibility remaining for 2026 and can still develop into quality players.

But the Gophers had more misses in the portal, especially along the defensive line and offensive lines.

“How do we have to vet players even more to find the right fit?” Fleck asked last week. “Gerrit Chernoff and (director of player personnel) Marcus Hendrickson do such a great job of that. They have learned from our past.”

The Gophers brought in more than 20 players last year. This year’s tally is to be determined, but the entire roster will be assessed for needs. The U has had a strong retention rate of current players on the roster, which cuts down on how many new players will be needed.

“It’s not going to be a massive number, because I feel really good about our retention rate,” Fleck said.

Minnesota will continue to look for players with multiple years of eligibility, players with developmental upside and ones who fit in with a program that emphasizes work in the classroom and the community.

The Gophers also don’t have the largest Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) budget, so they can’t wade too deeply into the overall transfer talent pool.

With the addition of revenue sharing, the other bucket of funds for players, missing on a paid-for prospect stings not only the on-field performance, but also the budget. It’s more real now, Coyle says.

“We do a lot of due diligence,” the AD said. “ Are you going to be 100% all the time? Absolutely not. But again, the closer you get to 100%, the better you are going to be long-term.”

The Gophers are believed to have three primary positions of need: defensive line, receiver and offensive line.

The return of D-end Anthony Smith for 2026 is a boost to the position, but veteran tackle help is a must with Deven Eastern, Jalen Logan-Redding and Lawrence out of eligibility.

Top receiver Le’Meke Brockington just finished his senior season, and quarterback Drake Lindsey needs more help on the outside. The two-touchdown performance in the Rate Bowl from rising junior Jalen Smith was a good sign, and Tracy will be back. But dynamism to create separation and win contested catches are coveted attributes.

The Gophers’ front five struggled mightily this season. Four of the pieces are back for 2026, but they will likely pursue at least one tackle with the exit of Ray.

Minnesota Gophers head football coach P.J. Fleck talks about the 2026 recruiting class during an event at Huntington Bank Stadium in Minneapolis on Dec. 3, 2025. (Trenten Gauthier / Gopher Athletics)

Gophers expected to hire Stanford assistant Bobby April as rush ends coach

While other programs tampered, Anthony Smith announces his return to Gophers for 2026

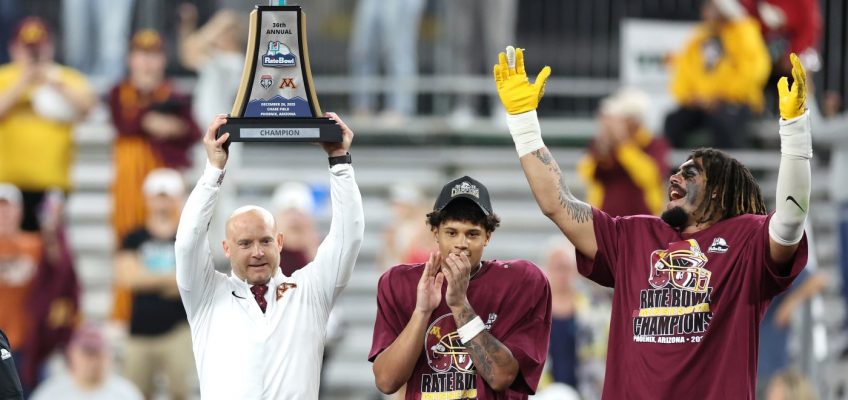

Gophers score walk-off win in Rate Bowl, 20-17 over New Mexico

Gophers receiver Jalen Smith steps up in Rate Bowl win

Gophers football vs. New Mexico: Keys to game, how to watch, who has edge