By JAKE COYLE

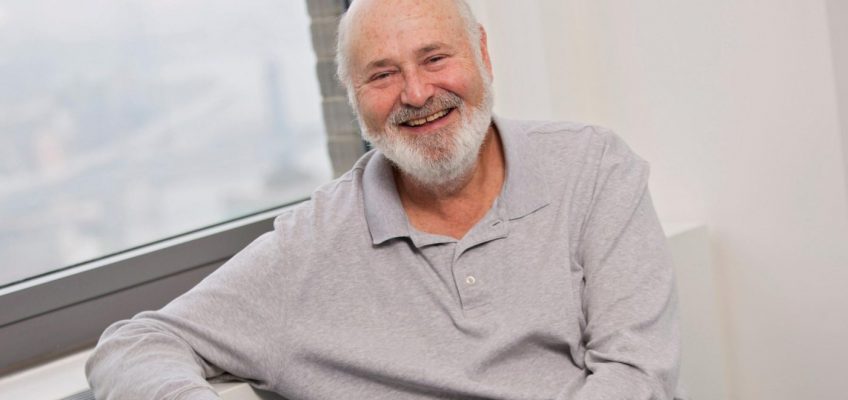

Rob Reiner, the son of a comedy giant who became one himself as one of the preeminent filmmakers of his generation with movies such as “The Princess Bride,” “When Harry Met Sally …” and “This Is Spinal Tap,” has died. He was 78.

Reiner and his wife, Michele Singer, were found dead Sunday at their home in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles. A law enforcement official briefed on the investigation confirmed their identities but could not publicly discuss details of the investigation and spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity.

Authorities were investigating an “apparent homicide,” said Capt. Mike Bland with the Los Angeles Police Department. The Los Angeles Fire Department said it responded to a medical aid request shortly after 3:30 p.m.

Reiner grew up thinking his father, Carl Reiner, didn’t understand him or find him funny. But the younger Reiner would in many ways follow in his father’s footsteps, working both in front and behind the camera, in comedies that stretched from broad sketch work to accomplished dramedies.

“My father thought, ‘Oh, my God, this poor kid is worried about being in the shadow of a famous father,’” Reiner said, recalling the temptation to change his name to “60 Minutes” in October. “And he says, ‘What do you want to change your name to?’ And I said, ‘Carl.’ I just wanted to be like him.”

After starting out as a writer for “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” Reiner’s breakthrough came when he was, at age 23, cast in Norman Lear’s “All in the Family” as Archie Bunker’s liberal son-in-law, Michael “Meathead” Stivic. But by the 1980s, Reiner began as a feature film director, churning out some of the most beloved films of that, or any, era. His first film, the largely improvised 1984 cult classic “This Is Spinal Tap,” remains the quintessential mockumentary.

After the 1985 John Cusack summer comedy, “The Sure Thing,” Reiner made “Stand By Me” (1986), “The Princess Bride” (1987) and “When Harry Met Sally …” (1989), a four-year stretch that resulted in a trio of American classics, all of them among the most often quoted movies of the 20th century.

A legacy on and off screen

For the next four decades, Reiner, a warm and gregarious presence on screen and an outspoken liberal advocate off it, remained a constant fixture in Hollywood. The production company he co-founded, Castle Rock Entertainment, launched an enviable string of hits, including “Seinfeld” and “The Shawshank Redemption.” By the turn of the century, its success rate had fallen considerably, but Reiner revived it earlier this decade. This fall, Reiner and Castle Rock released the long-in-coming sequel “Spinal Tap II: The End Continues.”

All the while, Reiner was one of the film industry’s most passionate Democrat activists, regularly hosting fundraisers and campaigning for liberal issues. He was co-founder of the American Foundation for Equal Rights, which challenged in court California’s ban on same-sex marriage, Proposition 8. He also chaired the campaign for Prop 10, a California initiative to fund early childhood development services with a tax on tobacco products. Reiner was also a critic of President Donald Trump.

That ran in the family, too. Reiner’s father opposed the Communist hunt of McCarthyism in the 1950s and his mother, Estelle Reiner, a singer and actor, protested the Vietnam War.

“If you’re a nepo baby, doors will open,” Reiner told the Guardian in 2024. “But you have to deliver. If you don’t deliver, the door will close just as fast as it opened.”

‘All in the Family’ to ‘Stand By Me’

Robert Reiner was born in the Bronx on March 6, 1947. As a young man, he quickly set out to follow his father into entertainment. He studied at the University of California, Los Angeles film school and, in the 1960s, began appearing in small parts in various television shows.

But when Lear saw Reiner as a key cast member in “All in the Family,” it came as a surprise to the elder Reiner.

“Norman says to my dad, ‘You know, this kid is really funny.’ And I think my dad said, ‘What? That kid? That kid? He’s sullen. He sits quiet. He doesn’t, you know, he’s not funny.’ He didn’t think I was anyway,” Reiner told “60 Minutes.”

On “All in the Family,” Reiner served as a pivotal foil to Carroll O’Connor’s bigoted, conservative Archie Bunker. Reiner was five times nominated for an Emmy for his performance on the show, winning in 1974 and 1978. In Lear, Reiner also found a mentor. He called him “a second father.”

“It wasn’t just that he hired me for ‘All in the Family,’” Reiner told “American Masters” in 2005. “It was that I saw, in how he conducted his life, that there was room to be an activist as well. That you could use your celebrity, your good fortune, to help make some change.”

Lear also helped launch Reiner as a filmmaker. He put $7.5 million of his own money to help finance “Stand By Me,” Reiner’s adaptation of the Stephen King novella “The Body.” The movie, about four boys who go looking for the dead body of a missing boy, became a coming-of-age classic, made breakthroughs of its young cast (particularly River Phoenix) and even earned the praise of King.

With his stock rising, Reiner devoted himself to adapting William Goldman’s 1973’s “The Princess Bride,” a book Reiner had loved since his father gave him a copy as a gift. Everyone from François Truffaut to Robert Redford had considered adapting Goldman’s book, but it ultimately fell to Reiner (from Goldman’s own script) to capture the unique comic tone of “The Princess Bride.” But only once he had Goldman’s blessing.

“At the door he greeted me and he said, ‘This is my baby. I want this on my tombstone. This is my favorite thing I’ve ever written in my life. What are you going to do with it?’” Reiner recalled in a Television Academy interview. “And we sat down with him and started going through what I thought should be done with the film.”

Though only a modest success in theaters, the movie — starring Cary Elwes, Mandy Patinkin, Wallace Shawn, André the Giant and Robin Wright — would grow in stature over the years, leading to countless impressions of Inigo Montoya’s vow of revenge and the risky nature of land wars in Asia.

‘When Harry Met Sally …”

Reiner was married to Penny Marshall, the actor and filmmaker, for 10 years beginning in 1971. Like Reiner, Marshall experienced sitcom fame, with “Laverne & Shirley,” but found a more lasting legacy behind the camera.

After their divorce, Reiner, at a lunch with Nora Ephron, suggested a comedy about dating. In writing what became “When Harry Met Sally …” Ephron and Reiner charted a relationship between a man and a woman (played in the film by Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan) over the course of 12 years.

Along the way, the movie’s ending changed, as did some of the film’s indelible moments. The famous line, “I’ll have what she’s having,” said after witnessing Ryan’s fake orgasm at Katz’s Delicatessen, was a suggestion by Crystal — delivered by none other than Reiner’s mother, Estelle.

The movie’s happy ending also had some real-life basis. Reiner met Singer, a photographer, on the set of “When Harry Met Sally …” In 1989, they were wed. They had three children together: Nick, Jake and Romy.

Reiner’s subsequent films included another King adaptation, “Misery” (1990) and a pair of Aaron Sorkin-penned dramas: the military courtroom tale “A Few Good Men” (1992) and 1995’s “The American President.”

By the late ’90s, Reiner’s films (1996’s “Ghosts of Mississippi,” 2007’s “The Bucket List”) no longer had the same success rate. But he remained a frequent actor, often memorably enlivening films like “Sleepless in Seattle” (1993) and “The Wolf of Wall Street” (2013). In 2023, he directed the documentary “Albert Brooks: Defending My Life.”

In an interview earlier this year with Seth Rogen, Reiner suggested everything in his career boiled down to one thing.

“All I’ve ever done is say, ‘Is this something that is an extension of me?’ For ‘Stand by Me,’ I didn’t know if it was going to be successful or not. All I thought was, ‘I like this because I know what it feels like.’”