Chris Joyner | The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (TNS)

It’s been 3 1/2 years since thousands of people marched from a rally by then-President Donald Trump to the U.S. Capitol, where many of them stayed for hours, fighting with police and parading through the building, delaying the certification of the presidential election and forcing members of Congress to flee.

But even as Americans prepare for another presidential election in November, the sprawling investigation into the Jan. 6, 2021, riot that followed lingers on.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, at least 1,457 people have been charged with crimes ranging from misdemeanor trespassing to serious felonies, including assault on a police officer and seditious conspiracy. Among those are 33 defendants with ties to Georgia, two of whom are scheduled to go on trial Monday.

Phillip “Bunky” Crawford, 48, and Dominic Box, 34, are scheduled for separate trials Monday in U.S. District Court in Washington on felony charges related to their alleged actions in the riot.

Crawford pleaded guilty last month to one count of felony civil disorder, four counts of assaulting police and one count of violent and disorderly conduct on the Capitol grounds. But he chose to take the remaining five criminal charges against him to trial. Four of those remaining charges involve allegations that he used a dangerous or deadly weapon and could bring even more time in prison.

Unlike many of his fellow defendants, Crawford did not enter into a plea deal with federal prosecutors, which would have avoided a trial. In a lengthy May 31 interview on the streaming platform Rumble, Crawford described his decision as both a principled and strategic decision.

“I pled guilty to six counts because I realized (prosecutors) are not following the Constitution and people aren’t winning. I’m looking at the previous cases, and it don’t look good,” he said. “I took the plea to take responsibility for my actions, because I did put my hands on officers and they can hold me accountable for that. By the same token, (the officers) should be held accountable for their actions.”

Related Articles

New voter registration rules threaten hefty fines, criminal penalties for groups

AI experimentation is high risk, high reward for low-profile political campaigns

Biden’s campaign announces a $50 million advertising blitz highlighting Trump’s conviction

Tobacco-like warning label for social media sought by US surgeon general who asks Congress to act

Biden plan to save Medicare patients money on drugs risks empty shelves, pharmacists say

Crawford was among dozens of rioters who fought with police guarding a tunnel on the Capitol’s Lower West Terrace while members of Congress evacuated the building. The hand-to-hand combat between rioters and police was among the most violent moments of the day. Crawford defended his actions by saying he was attempting to reach a woman at the front of the police line whom he said was being beaten by police.

“I took action because what I saw was officers using excessive force. I’m not going to steer away from that,” he said. “When it is all said and done and my jail time is over, I can live with my head up.”

In court documents, federal prosecutors have repeatedly told the court that Crawford is unrepentant and believes in the “righteousness of his actions.” While Crawford portrays himself as a family man and a patriot, prosecutors also pointed to his history of arrests that include lying to police and violating parole as evidence of his poor character.

In the other trial scheduled Monday, Box faces charges of obstruction of an official proceeding and two counts of civil disorder, all felonies. Prior to the 2020 election, Box was known in Savannah as a prominent member of a group that spread conspiracy theories associated with the QAnon movement. On Jan. 6, Box livestreamed his march to the Capitol and portions of his time inside the building.

Box has a long history of drug and alcohol problems and was arrested in August on charges including DUI in Jacksonville, Florida, after police reportedly found him passed out in the driver’s seat of his car in the parking lot of a Mexican restaurant. He has been in jail in Jacksonville since his arrest awaiting trial on those charges.

Since the riot, two dozen Georgia defendants have either entered into plea deals or been found guilty at trial on Jan. 6 charges, receiving sentencing ranging from probation to years in prison. They join nearly 900 others from across the nation who have met the same fate.

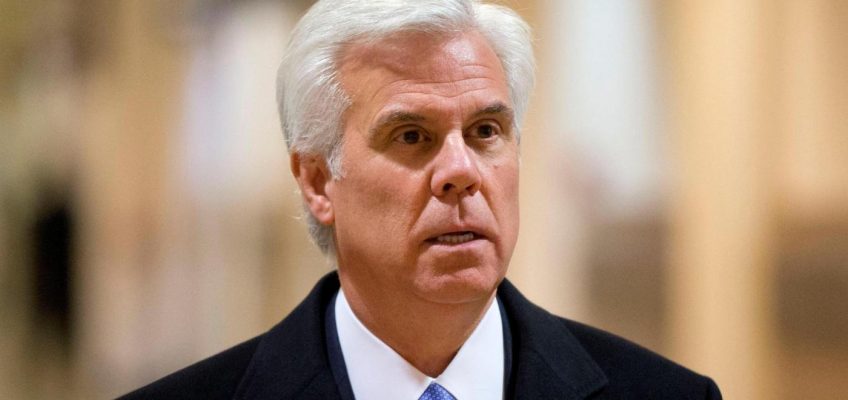

“I think it’s safe to say that almost everyone who went to the Capitol that day knows someone who was arrested or got a door knock from the FBI,” said Jon Lewis, a research fellow at George Washington University’s Program on Extremism.

At the same time, Lewis said it is hard to see whether the investigation and prosecutions will have the effect of deterring more political violence in this coming election cycle. Lewis pointed to the recent example of convicted Jan. 6 rioter Brandon Fellows — sentenced to 3 1/2 years in prison for his role in the riot — who not only returned to the Capitol, but sat behind Dr. Anthony Fauci during a congressional hearing this month, making faces at the cameras.

“You have individuals who are looking at these arrests and these prosecutions and see it as nothing more than politically motivated theater,” Lewis said. “And yet we are still here just talking about the 1,400th low-level defendant who probably will not get jail time and whose statute of limitation will run out if they aren’t pardoned by a new Trump administration.”

Holding the rioters accountable in court is admirable, Lewis said. But the root causes of the unrest remain largely unaddressed.

“We can’t confuse that with strategic success,” he said.

Lewis said the rise of far-right “influencers” on social media over the past four years has kept alive many of the same conspiratorial themes that led to violence on Jan. 6. The “most damning part” is the lack of outrage from congressional Republicans who were evacuated on Jan. 6 as rioters breached the building, he said.

“We’re still talking about the same challenges we were four years ago,” he said.

©2024 The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Visit at ajc.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.