Today is Saturday, Aug. 24, the 237th day of 2024. There are 129 days left in the year.

Today in history:

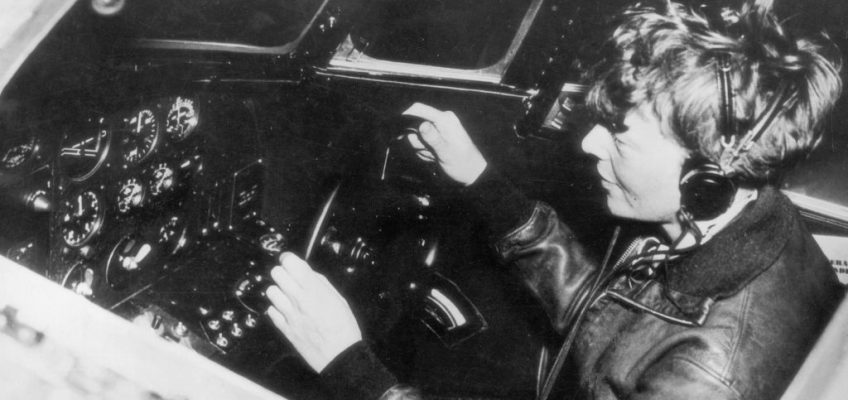

On August 24, 1932, Amelia Earhart embarked on a 19-hour flight from Los Angeles to Newark, New Jersey, making her the first woman to fly solo, non-stop, from coast to coast.

Also on this date:

In 1814, during the War of 1812, British forces invaded Washington, D.C., setting fire to the still-under-construction Capitol and the White House, as well as other public buildings.

Related Articles

Today in History: August 23, the largest farm worker strike in U.S.

Today in History: August 22, first America’s Cup trophy

Bill Clinton’s post-presidential journey: a story told in convention speeches

Today in History: August 21, Nat Turner launches rebellion

Today in History: August 20, Soviets invade Czechoslovakia

In 1912, Congress passed a measure creating the Alaska Territory.

In 1949, the North Atlantic Treaty came into force.

In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Communist Control Act, outlawing the Communist Party in the United States.

In 1981, Mark David Chapman was sentenced in New York to 20 years to life in prison for murdering John Lennon.

In 1989, Baseball Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti (juh-MAH’-tee) banned Pete Rose from the game for betting on his own team, the Cincinnati Reds.

In 1991, in response to a coup attempt by hardline Communist leaders attempting to reassert control over the Soviet Union, Ukrainian parliamentarians voted to approve a Declaration of Independence for the state of Ukraine.

In 1992, Hurricane Andrew smashed into Florida; the storm resulted in 65 deaths and caused more than $26 billion in damage across Florida, Louisiana and the Bahamas.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union declared that Pluto was no longer a full-fledged planet, demoting it to the status of a “dwarf planet.”

In 2012, a Norwegian court found Anders Behring Breivik guilty of terrorism and premeditated murder for twin attacks on July 22, 2011 that killed 77 people; he received a 21-year prison sentence that can be extended as long as he is considered dangerous to society.

In 2018, the family of Arizona Sen. John McCain announced that he had discontinued medical treatment for an aggressive form of brain cancer; McCain died the following day.

In 2019, police in Aurora, Colorado, responding to a report of a suspicious person, used a chokehold to subdue Elijah McClain, a 23-year-old Black man; he suffered cardiac arrest on the way to the hospital and was later declared brain dead and taken off life support.

In 2020, Republicans formally nominated President Donald Trump for a second term on the opening day of a scaled-down convention; during a visit to the convention city of Charlotte, North Carolina, Trump told delegates that “ the only way they can take this election away from us is if this is a rigged election. ”

Today’s Birthdays:

Composer-musician Mason Williams is 86.

R&B singer Marshall Thompson (The Chi-Lites) is 82.

WWE co-founder Vince McMahon is 79.

Author Paulo Coelho is 77.

Actor Anne Archer is 77.

Author Alexander McCall Smith is 76.

Composer Jean-Michel Jarre is 76.

Author Orson Scott Card is 73.

Poet Linton Kwesi Johnson is 72.

Actor Kevin Dunn is 69.

Former Arkansas governor and political commentator Mike Huckabee is 69.

Actor-writer Stephen Fry is 67.

Actor Steve Guttenberg is 66.

Baseball Hall of Famer Cal Ripken Jr. is 64.

Actor Jared Harris is 63.

Talk show host Craig Kilborn is 62.

Actor Marlee Matlin is 59.

Basketball Hall of Famer Reggie Miller is 59.

Film director Ava DuVernay is 52.

Actor-comedian Dave Chappelle is 51.

Actor James D’Arcy is 50.

Actor Carmine Giovinazzo (jee-oh-vihn-AH’-zoh) is 51.

Actor Alex O’Loughlin is 48.

Author John Green is 47.

Actor Chad Michael Murray is 43.

Actor Rupert Grint is 36.

Basketball player Kelsey Plum is 30.