With a presidential election on the horizon, just about every screen will be dominated by campaign coverage. When you’re ready for a palate cleanser, the fall TV season has plenty on offer.

Even so, it’s not the deluge of the recent past.

Six hundred scripted shows premiered in 2022. That was never going to be realistic long-term and media companies have cut back. But it’s also made the professional lives of screenwriters and others in Hollywood more precarious than ever (unless you’re a big-name star). Overall, Hollywood remains in a state of flux, with layoffs at Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery and Paramount Global. The latter — which is the parent company to a sizable chunk of TV operations, including CBS, Showtime, Comedy Central and Paramount+ — may or may not have a new owner by the time you read this, with two rival bids duking it out. What either outcome means for you, the viewer, is unclear.

I would be remiss for not mentioning that one of the best shows in recent memory isn’t premiering this fall; it just became available on Netflix and is probably new to most viewers. That would be AMC’s “Interview with the Vampire,” which is smart and funny and far better than any adaptation has a right to be. I don’t even like vampire stories, but here I am, in the bag for this one.

With that out of the way, here’s a snapshot of the coming weeks, presented in chronological order. It’s a fever dream of adaptations because Hollywood’s love affair with IP (intellectual property) continues unabated.

Gary Oldman in Season 4 of “Slow Horses.” (Apple TV+)

“Slow Horses” (Sept. 4 on Apple TV+): The British spy series returns for Season 4 with an adaptation of Mick Herron’s “Spook Street,” which centers Jonathan Pryce’s recurring character, who may not be long for this world: “What happens when an old spook loses his mind? Does the Service have a retirement home for those who know too many secrets but don’t remember they’re secret? Or does someone take care of the senile spy for good?”

“Fight Night: The Million Dollar Heist” (Sept. 5 on Peacock): Adapted from a true-crime podcast, the limited series tells the story of an armed robbery that took place on the night of Muhammad Ali’s 1970 comeback fight in Atlanta. Here’s how the podcast describes the crime: After the fight, guests attending an after-party (thrown by a hustler known as Chicken Man) were greeted not with food and drink, but the barrel of a sawed-off shotgun. Starring Kevin Hart as Chicken Man and Don Cheadle as the police detective assigned to the case.

Harris will sit down with CNN for her first interview since launching presidential bid

Though retired from TV, Randy Shaver is still on the high school football beat

Quiz: Will you be voting for ‘The Bear’ at this year’s Emmys?

Hollywood is slowly getting back to work, but the days of peak TV aren’t coming back

‘Pachinko’ returns with Season 2, a more muted but necessary chapter in the series

“How to Die Alone” (Sept. 13 on Hulu): Natasha Rothwell (“Insecure” and “The White Lotus”) stars in this comedy as a millennial stuck in a miserable existence: “I’m broke, my family thinks I’m a lost cause, my love life is a joke and the punchline is, I work at an airport.” A brush with death prompts her to start taking chances.

“Three Women” (Sept. 13 on Starz): The drama centers on the lives of three women (talk about an accurate title!) including a suburban housewife who begins an extramarital affair, an entrepreneur navigating an open marriage and a student who accuses a teacher of an inappropriate relationship. All three tell their stories to a character played by Shailene Woodley.

“Moonflower Murders” (Sept. 15 on PBS Masterpiece): A former book editor living in Greece and running a hotel (played by Lesley Manville) is drawn back into her old literary world when she’s asked to figure out whether a novel about a murder is fact or fiction. Based on the book by Anthony Horowitz.

“Agatha All Along” (Sept. 18 on Disney+): “WandaVision” was the first Marvel TV series to premiere on the streamer and it remains the best. That’s because it eschewed your typical superhero storyline in favor of the cheeky and bizarre, plunking down a couple of MCU characters into various sitcom templates of old. It also featured a very funny performance from Kathryn Hahn, and her character’s long-gestating, witch-focused spinoff is finally here. The teaser suggests the show will be entirely different in tone and interests than its predecessor. That’s not a selling point for me, but Hahn is so … decisions, decisions.

“The Penguin” (Sept. 19 on HBO): This eight-episode TV series from DC Studios puts Batman nemesis The Penguin front and center, played by Colin Farrell under 576 layers of prosthetics. (I’m exaggerating, but he’s as unrecognizable as he was in 2022’s “The Batman.”) The premise is very Batman-saga-meets-the-Italian mob.

“Frasier” (Sept. 19 on Paramount+): I wasn’t a fan of the first season of this reboot, which had no understanding of what made Frasier Crane — and the people surrounding him — so much fun. But here we are with Season 2, which is loading up on guest stars from the original show — including Dan Butler as Bob “Bulldog” Briscoe, Edward Hibbert as Gil Chesterton and Harriet Sansom Harris as Frasier’s agent, Bebe Glazer — with Frasier returning to his own radio station in Seattle for an episode. Peri Gilpin, who played Roz, will also appear as a recurring character.

“A Very Royal Scandal” (Sept. 19 on Amazon): In 2019, Britain’s Prince Andrew gave a now-infamous TV interview about his involvement with Jeffrey Epstein, which ultimately led to him withdrawing from official royal duties. The backstory of how that interview came together has already been adapted for the screen by Netflix and it was a pointless exercise with a self-congratulatory tone. But at least it was only a movie-length treatment. Amazon’s upcoming version is spread out over three episodes and stars Michael Sheen and Ruth Wilson.

Kathy Bates stars as the brilliant septuagenarian Madeline Matlock in the new drama series “Matlock.” (Brooke Palmer/CBS)

“Matlock” (Sept. 22 on CBS): The original “Matlock” of the 1980s and ’90s was an Atlanta-set legal drama starring Andy Griffith. This new version has an actor just as beloved at its center — Kathy Bates — but the premise is slightly different. She plays Madeline Matlock, a folksy defense attorney who, thanks to her rotten finances, can’t retire just yet, so she seeks out an entry-level job at a slick corporate firm in New York. But the real story — her real motivation for working there — is more complicated. That part makes up the ongoing storyline, while each week there’s a new client to defend.

From left: Joaquin Cosio, Diego Calva, Sergio Bautista and Renata Vaca in “Midnight Family.” (Apple TV+)

“Midnight Family” (Sept. 24 on Apple TV+ ): The Spanish-language series follows a med student in Mexico City who moonlights as part of her family’s privately-owned ambulance service. It’s adapted from the absorbing 2019 documentary of the same title, which is well worth seeking out whether you plan to watch the Apple series or not (it’s streaming free on Pluto). Here’s a bit from my write-up when it screened locally:

“Mexico City has a population of 9 million, but according to a figure provided at the film’s beginning, the government operates fewer than 45 emergency ambulances. Privately operated ambulances attempt to fill in those gaps and director Luke Lorentzen’s high-adrenaline vérité film offers an immersive look at this underground economy, as seen through the eyes of one family-run business. … The documentary is the antithesis of eat-your-vegetables filmmaking. It has the intensity of an action film and the moodiness of a noir. It’s thrillingly shot and incredibly thought-provoking. It’s one of my favorite documentaries in recent memory. … You worry for everyone — patients (who are having one of the worst days of their lives) and paramedics alike. The latter are frequently stopped by police, who shake them down for bribes. This becomes a major impediment; they are barely getting by.”

“The Last Days of the Space Age” (Oct. 2 on Hulu): Starring “Chicago Fire” alum Jesse Spencer, this eight-part dramedy is set in Perth, Australia. The year is 1979: Power workers are on strike, the city is hosting the Miss Universe pageant and the U.S. space station, Skylab, is about to crash nearby. According to the show’s description: “Against this backdrop of international cultural and political shifts, three families in a tight-knit coastal community find their marriages, friendships and futures put to the test.”

“Disclaimer” (Oct. 11 on Apple TV+): Cate Blanchett stars in this limited series from Alfonso Cuarón playing a powerful and celebrated journalist whose personal secrets are revealed in a novel by an unknown author played by Kevin Kline, who is looking to humiliate the woman he believes is responsible for his own pains and losses. Sacha Baron Cohen plays her wealthy husband.

“Ghosts” (Oct. 17 on CBS): This sitcom about the misadventures of ghosts trapped in a manor house and their human companions wasn’t nominated for a best comedy Emmy this year, despite being one of the funniest shows on TV right now. Much as I admire “The Bear,” which is nominated for best comedy, here’s a show that’s consistently comedic each episode … but I digress.

“Poppa’s House” (Oct. 21 on CBS): Starring Damon Wayans and Damon Wayans Jr. as father and son, the idea for the sitcom came about when a house across the street from Wayans Jr. became available and Wayans Sr. considered buying it. And then he reconsidered. “I was like, ‘Hell no!’ because their mother would be like, ‘Go to your Poppa’s house!’ Everybody would be sending them to me,” he said in a recent interview. “I told my agent, and he said, ‘That’s a show!’”

“Before” (Oct. 25 on Apple TV+): Billy Crystal stars in this 10-episode psychological thriller as a widower and child psychiatrist treating a young patient who has a haunting connection to his past. A rare dramatic role for Crystal.

“The Marlow Murder Club” (Oct. 27 on PBS Masterpiece): From the creator of “Death in Paradise” (yet another Masterpiece mainstay) comes the TV adaptation of “The Marlow Murder Club” book series, which follows a retired archaeologist who teams up with a dog walker and a vicar’s wife. Together they become an amateur trio of sleuths in England, piecing together clues and grilling witnesses.

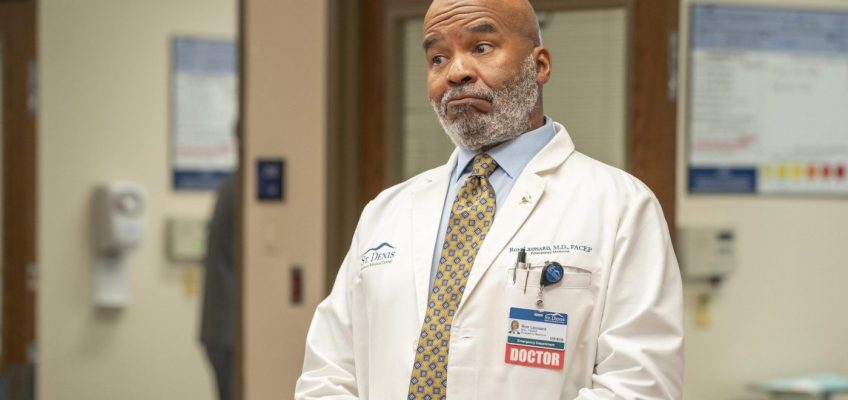

“St. Denis Medical” (Nov. 12 on NBC): We haven’t had a hospital comedy on network TV since “Scrubs.” This one is a mockumentary from Justin Spitzer (“Superstore”), but another clear inspiration here is “The Office.” The trailer looks promising! Hopefully the show will be able to score some satirical points about how absurd and frustrating so much of our health care system has become. Among the cast are comedic ringers including David Alan Grier, “Superstore” alum Kaliko Kauahi, Wendi McLendon-Covey (now freed up from her long run on “The Goldbergs”) and Allison Tolman.

“Cross” (Nov. 14 on Amazon): Aldis Hodge (“Leverage”) stars in this TV adaptation of the Alex Cross book series as a detective and forensic psychologist who digs into the psyches of killers and their victims in order to identify — and ultimately capture — the culprits.

“Landman” (Nov. 17 on Paramount+): Starring Billy Bob Thornton, the series is set amid the oil boomtowns of Texas and is based on the podcast “Boomtown,” offering an “upstairs/downstairs story of roughnecks and wildcat billionaires fueling a boom so big, it’s reshaping our climate, our economy and our geopolitics.” Would it surprise you to learn the series was created by “Yellowstone’s” Taylor Sheridan, who has become the key force behind most of Paramount+’s recent output?

Nina Metz is a Tribune critic.