Venezuela’s defense minister on Sunday rejected any notion that the United States would “run” his country, projecting an official line of defiance as the Trump administration said it would seek to exert “leverage” over the country’s leadership.

The White House has said it believes that Venezuela’s government, under interim leader Delcy Rodríguez, will fall in line and largely comply with its demands after the capture of President Nicolás Maduro. The nature of the private conversations between Venezuela’s government and U.S. officials is unclear.

Publicly, Rodríguez and the defense minister, Vladimir Padrino López, have said the government that was in place under Maduro is still in charge. In a fiery speech broadcast Sunday on state television, Padrino López channeled decades of Venezuelan nationalism and said that the country’s armed forces would “continue to employ all its available capabilities for military defense, the maintenance of internal order and the preservation of peace.”

“Our sovereignty has been violated and breached,” he said, backed by uniformed soldiers. Padrino López said that U.S. forces had killed a “large part” of Maduro’s security detail in the raid that apprehended him, part of a death toll of soldiers and civilians that rose to 80 Sunday.

Maduro is in a New York City jail with his wife, who were both indicted on federal drug trafficking and weapons charges. They are expected to make their initial appearances in federal court Monday.

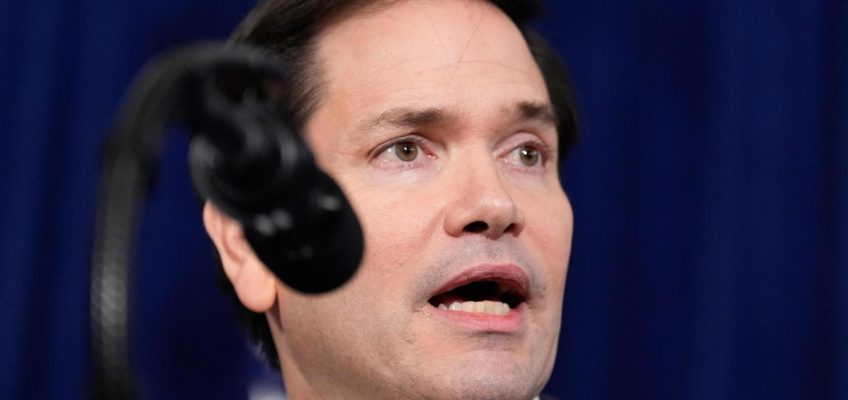

In a series of television appearances Sunday, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio said that the U.S. military would maintain a “quarantine” around Venezuela to prevent the entry and exit of oil tankers under U.S. sanctions.

But though President Donald Trump has said the United States intends to “run” Venezuela and reclaim American oil interests after ousting Maduro, Pentagon officials said that there were currently no U.S. military personnel in the country.

In an interview with CBS News’ “Face the Nation,” Rubio said the large U.S. naval force amassed in the Caribbean Sea off Venezuela will remain “until we see changes, not just to further the national interest of the United States, which is No. 1, but also that lead to a better future for the people of Venezuela.”

Trump administration officials indicated that the large U.S. military force, which includes 15,000 troops as well as aircraft and warships, was a signal to the Venezuelan authorities that they must act more favorably toward the United States or risk what Trump called a “second wave” of attacks.

Here’s what else to know:

— Oil reserves: Rubio focused Sunday, as Trump did a day earlier, on the opportunities for American companies in Venezuela’s oil sector, and on the need for Venezuelan officials to clamp down on drug trafficking. Trump made clear his desire to open up Venezuela’s vast state-controlled oil reserves to American oil companies, saying, “We are going to run the country right.” But U.S. intervention could prove complicated and expensive.

— U.S. strike: At least 80 Venezuelans, including civilians and soldiers, were killed in the Caracas raid early Saturday, according to a senior Venezuelan official. No U.S. service members were killed.

— Drug charges: An indictment unsealed by a federal judge in New York City charged Maduro, his wife, Cilia Flores, and four others with four counts, including narco-terrorism, conspiracy to import cocaine and possession of machine guns. Despite the U.S. focus on cocaine trafficking, experts say Venezuela’s role in that trade is modest. Maduro was being held at Brooklyn’s Metropolitan Detention Center, and he and Flores were expected to make their first appearance in Manhattan federal court soon.

— Protests and celebrations: Some people took to the streets of Chicago and Washington on Saturday to protest the U.S. military intervention. Venezuelan migrants in New York cheered Maduro’s removal from power.

— Nobel winner: Venezuela’s main opposition leader, María Corina Machado, who recently won the Nobel Peace Prize, posted a statement asking that her political ally, Edmundo González, be recognized as Venezuela’s president immediately. Machado had sought in recent months to curry favor with Trump, but he said Saturday that she lacked the “respect” needed to govern Venezuela.

Related Articles

Venezuelans wonder who’s in charge as Trump claims contact with Maduro’s deputy

US military operation in Venezuela disrupts Caribbean holiday travel, hundreds of flights canceled

How the US captured Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro

A timeline of the US military’s buildup near Venezuela and attacks on alleged drug boats

US plans to ‘run’ Venezuela and tap its oil reserves, Trump says, after operation to oust Maduro