By MATTHEW DALY, Associated Press

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Trump administration said Monday it will open 13 million acres of federal lands for coal mining and provide $625 million to recommission or modernize coal-fired power plants as President Donald Trump continues his efforts to reverse the year-long decline in the U.S. coal industry.

Related Articles

Ticks are migrating, raising disease risks if they can’t be tracked quickly enough

Hurricane Helene hit the reset button on one town’s goal of becoming an outdoor tourism mecca

LA County response to deadly fires slowed by lack of resources, outdated alert process, report says

At UN, Trump attacks climate change efforts in front of leaders of drowning nations

Federal judge lifts Trump administration’s halt of nearly complete offshore wind farm in New England

Actions by the Energy and Interior departments and the Environmental Protection Agency follow executive orders Trump issued in April to revive coal, a reliable but polluting energy source that’s long been shrinking amid environmental regulations and competition from cheaper natural gas.

Environmental groups denounced announcement, which come as the Trump administration has clamped down on renewable energy, including freezing permits for offshore wind projects, ending clean energy tax credits and blocking wind and solar projects on federal lands.

Under Trump’s orders, the Energy Department has required fossil-fueled power plants in Michigan and Pennsylvania to keep operating past their retirement dates to meet rising U.S. power demand amid growth in data centers, artificial intelligence and electric cars. The latest announcement would allow those efforts to expand as a precaution against possible electricity shortfalls.

Trump also has directed federal agencies to identify coal resources on federal lands, lift barriers to coal mining and prioritize coal leasing on U.S. lands. A sweeping tax bill approved by Republicans and signed by Trump reduces royalty rates for coal mining from 12.5% to 7%, a significant decrease that officials said will help ensure U.S. coal producers can compete in global markets.

‘Mine baby, mine’

The new law also mandates increased availability for coal mining on federal lands and streamlines federal reviews of coal leases.

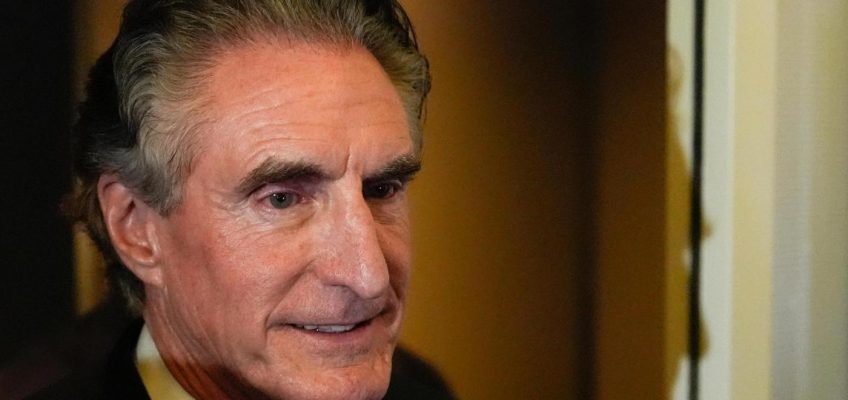

“Everybody likes to say, ‘drill baby, drill.’ I know that President Trump has another initiative for us, which is ‘mine baby, mine,’” Interior Secretary Doug Burgum said at a news conference Monday at Interior headquarters. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin and Energy Undersecretary Wells Griffith also spoke at the event. All three agencies signed orders boosting coal.

“By reducing the royalty rate for coal, increasing coal acres available for leasing and unlocking critical minerals from mine waste, we are strengthening our economy, protecting national security and ensuring that communities from Montana to Alabama benefit from good-paying jobs,” Burgum said.

Zeldin called coal a reliable energy source that has supported American communities and economic growth for generations.

“Americans are suffering because the past administration attempted to apply heavy-handed regulations to coal and other forms of energy it deemed unfavorable,” he said.

Trump has clamped down on renewable energy

Environmental groups said Trump was wasting federal tax dollars by handing them to owners of the oldest, most expensive and dirtiest source of electricity.

“Subsidizing coal means propping up dirty, uncompetitive plants from last century – and saddling families with their high costs and pollution, said Ted Kelly, clean energy director for the Environmental Defense Fund. “We need modern, affordable clean energy solutions to power a modern economy, but the Trump administration wants to drag us back to a 1950s electric grid.”

Solar, wind and battery storage are the cheapest and fastest ways to bring new power to the grid, Kelly and other advocates said. “It makes no sense to cut off your best, most affordable options while doubling down on the most expensive ones,” Kelly said.

The EPA said Monday it will open a 60-day public comment period on potential changes to a regional haze rule that has helped reduce pollution-fueled haze hanging over national parks, wilderness areas and tribal reservations. Zeldin announced in March that the haze rule would be among dozens of landmark environmental regulations that he plans to roll back or eliminate, including a 2009 finding that climate change harms human health and the environment.

Coal production has dropped steeply

Burgum, who also chairs Trump’s National Energy Dominance Council, said the actions announced Monday, along with the tax law and previous presidential and secretarial orders, will ensure “abundant, affordable energy while reducing reliance on foreign sources of coal and minerals.”

The Republican president has long promised to boost what he calls “beautiful” coal to fire power plants and for other uses, but the industry has been in decline for decades.

Related Articles

Trump takes his tariff war to the movies announcing 100% levies on foreign-made films

Dar Global to launch a $1 billion project in Saudi Arabia in a deal with Trump Organization

What we know about Trump’s peace proposal for Gaza

Trump’s big bill is prompting urgent action in some Democratic states, but not in Republican ones

Airspace violations force NATO to tread a tightrope, deterring Russia without hiking tensions

Coal once provided more than half of U.S. electricity production, but its share dropped to about 15% in 2024, down from about 45% as recently as 2010. Natural gas provides about 43% of U.S. electricity, with the remainder from nuclear energy and renewables such as wind, solar and hydropower.

Energy experts say any bump for coal under Trump is likely to be temporary because natural gas is cheaper, and there’s a durable market for renewable energy such as wind and solar power no matter who holds the White House.

Associated Press writer Todd Richmond in Madison, Wisconsin contributed to this story.