By MATT BROWN, Associated Press

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Congressional Black Caucus kicked off its annual legislative conference this week, which has been upended by President Donald Trump’s second term and by the presence of National Guard patrols near the conference’s venue.

The 62-member caucus, all of whom are Democrats, gathered with business leaders, activists, policy experts, local government officials, and other professionals from across the country to strategize how to build its new agenda and to counter Trump’s policies, which have disrupted federal government programs that address civil rights, education, healthcare, housing, immigration and labor policy, among other areas.

While this year’s conference has featured the usual panels, strategy sessions and cocktail parties, many attendees hoped to hear from the “conscience of the Congress” — a moniker bestowed on the CBC for its civil rights work — about what lessons can be learned from American history for the current political climate, and how lawmakers would govern should they win future elections.

Here are some comments from the CBC lawmakers who attended this year’s conference:

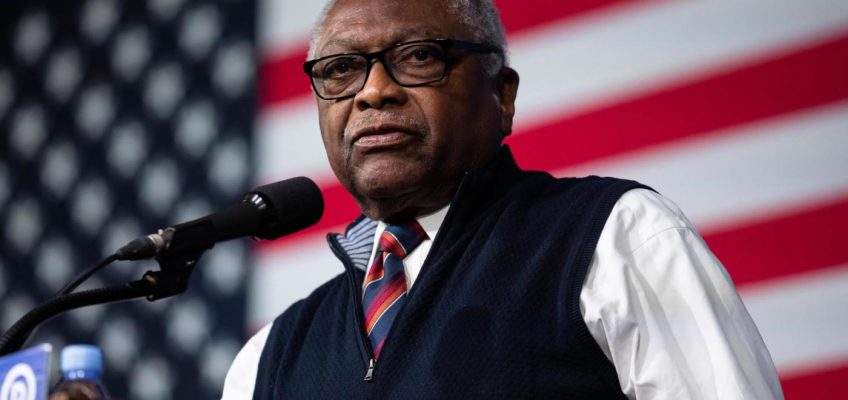

Rep. Jim Clyburn of South Carolina

“This is probably going to be one of the most consequential weeks that you have ever spent in your lives,” said Clyburn, the former House Democratic leader, during an address at the outset of the conference. “Take it from me: we are on the precipice of losing this democracy. We are. And if you don’t think so, take a journey through the history of the country.”

“I would hope that I would not leave this Earth, and my children and grandchildren would not be sentenced to having to live the life that their grandparents and parents lived,” said the 85-year-old congressman.

FILE – Incoming Congressional Black Caucus chair Yvette Clarke, D-N.Y., discusses caucus priorities for the 119th Congress and the Trump administration, Dec. 4, 2024, on Capitol Hill in Washington. (AP Photo/Mariam Zuhaib, File)

Rep. Yvette Clarke of New York

“This is not a conventional time. This is the time that we make for ourselves our own destiny,” Clarke, chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, said in an address to conference attendees.

“This is not a situation where we can necessarily say, well, look, those people in Congress have got it. Because the Congress is broken,” Clarke said. “We delivered democracy to the United States of America. Were it not for the abolitionists, were it not for the Civil Rights leaders, were it not for the foot soldiers on the ground, we’d still be living in apartheid. So let’s get it straight and let’s straighten up our backs.”

Clarke added: “I believe in us because were it not for the folks who came before me, I wouldn’t be standing here today as chairwoman of the largest Black Caucus in the history of the United States.”

FILE – State Sen. Jennifer McClellan, D-Hanover, speaks at The Call for Action on Gun Safety, Jan. 13, 2023, in Richmond, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark, File)

Rep. Jennifer McClellan of Virginia

“It’s not that if (Democrats) get the gavel, we rebuild back to what we had. We are also taking this opportunity to see what we can start from scratch,” said McClellan.

“There are some Republicans in the committee rooms, or in delegations, who share our concerns on some issues, whether it’s the NIH funding cuts, whether it’s First Amendment issues, or whether it’s clean energy rollbacks. And they are taking their concerns behind the scenes to the administration. And in some cases, they’ve been successful and at least making the bad less bad.”

FILE – Rep. Glenn Ivey, D-Md., joins elected officials and activists in a call to end the presence of National Guard troops in the District of Columbia on the order of President Donald Trump, at the Capitol in Washington, Sept. 4, 2025. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

Rep. Glenn Ivey of Maryland

“It’s going to be a new day, in part because they’ve changed the governing structure so much,” Ivey said of how Democrats are planning on governing in response to Trump’s changes to the federal government.

“Part of what we’re going to have to do is fire a big chunk of the bureaucracy that he’s putting in right now, just move them out and start over from scratch,” said Ivey, who represents the suburbs of Washington. “And we’ve got to make sure we understand that for a lot of the legislation we’ve done, we rely on particular government agencies to make it work. That’s not going to fly anymore. The Department of Justice and the Civil Rights Division is an example of that.”

FILE – Rep. Sydney Kamlager-Dove, D-Calif., speaks during a news conference on Capitol Hill, Sept. 11, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Mariam Zuhaib, File)

Rep. Sydney Kamlager-Dove of California

“The reality is that some of the bad stuff is just going to happen,” said Kamlager-Dove. “There is no strategy to stop some of the bad stuff except to continue to educate folks about the hypocrisy and the duplicity that is happening.”

“Many of these special elections, many of these local elections that are happening ever since Donald Trump came into office and started implementing his Project 2025, Democrats have been winning,” she said. “The strategy is to engage community-based organizations. The strategy is to work more diligently with our legal community. The strategy is to take everything to the court. The strategy is to create some outrage. The strategy is to fight the battles at the local elections. The facts of strategy are to make sure that we are shored up so that when 2028 comes around, folks are ready.”

Trump says he’s ordered the declassification and release of all government records on Amelia Earhart

Atlanta forfeits $37.5M in airport funds after refusing to agree to Trump’s DEI ban

Supreme Court keeps in place Trump funding freeze that threatens billions of dollars in foreign aid

Trump’s transportation department pulls trail and bike grants it deems ‘hostile’ to cars

Census Bureau to test using postal workers as census takers in 2030 field trials next year

Rep. Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts

“I think that the air feels a lot heavier than it does normally. That being said, after every session, after every engagement that I’ve had, I leave emboldened and more fortified,” said Pressley.

“It’s so important that we are leaning into community, but also that we are strategizing, that we are being intentional in our thought partnership and in our organizing, in the work of resistance and the work of reimagining,” she said. “So I would say, you know, in this moment right now, I feel very encouraged.”