By CARLOS RODRIGUEZ

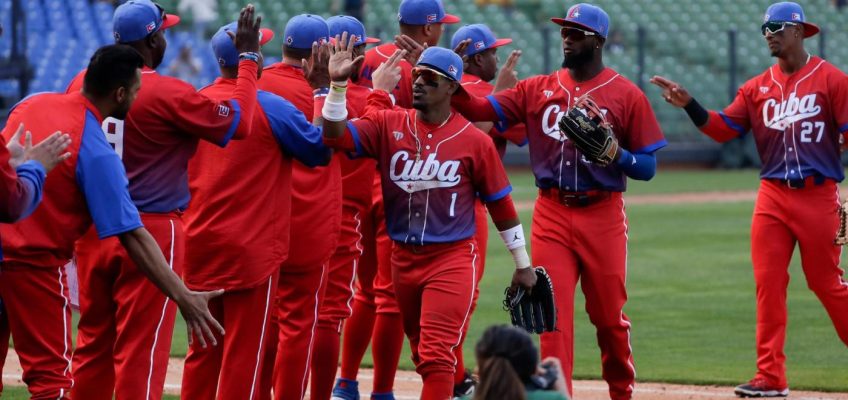

Eight members of Cuba’s delegation were denied visas to the United States for the World Baseball Classic, the Cuban Baseball and Softball Federation (FCBS) said Thursday.

Related Articles

State wrestling: Simley’s move to Section 1AA has major impact on individual tournaments

How did the Vikings grade out in the annual NFLPA report cards?

Amid controversy, Wild gold medalists express support for women’s team

Here’s how the Vikings can create more than $40 million in cap space

Olympics stars Alysa Liu, Ilia Malinin and other Team USA skaters coming to St. Paul in May

Cuba is set to play against Puerto Rico, Colombia, Panama and Canada in San Juan, Puerto Rico, during pool play of the WBC, which is scheduled from March 5-17.

Among the Cubans that were denied visas are FCBS president Juan Reinaldo Pérez Pardo and general secretary Carlos del Pino Muñoz. Pitching coach Pedro Luis Lazo was also denied.

A person with direct knowledge said all Cuban players and coaches except for Lazo received visas. The person spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity Thursday because no announcements have been made regarding player visas. The State Department declined to comment on the Cuban complaint citing visa privacy laws, but a U.S. official, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss the confidential matter, also said none of those denied visas are actual athletes but rather executives and officials.

“The United States’ response, after more than a month since these requests were submitted, ignores the reasons on which they are based, the most basic principles of sport, and the commitments assumed by the host countries of such events” the Federation said in a statement.

The Cubans finished third at the previous WBC in 2023. The team has exhibition games scheduled next week against the Kansas City Royals and the Cincinnati Reds in Arizona.

Cuba is among a list of seven countries with travel restrictions to the United States alongside Burundi, Laos, Sierra Leone, Togo, Turkmenistan and Venezuela.

Last year, the Cacique Mara team, from Maracaibo, Venezuela, was denied visas into the United States and missed the Senior Baseball World Series.

The Cuban Federation said that it “will analyze how to proceed, and will inform in due course.”

AP Baseball Writer Ronald Blum and Matthew Lee contributed to this report.

AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/MLB