“Our elected officials have a choice: be complicit in our displacement or successfully fight for these anti-displacement measures.”

A South West view of the Fulton Street and Van Sinderen Avenue intersection from one of Broadway Junction’s elevated platforms, pictured here in 2019.

The Broadway Junction area, which lies at the nexus of three communities—Bushwick, Ocean-Hill, Brownsville, and East New York—has been slated to receive nearly $1 billion in public and private investment. The public investment has the potential to be transformative in this disinvested area. However, government officials must learn from the past and put protections for local residents in place to prevent speculation-induced displacement.

In 2023, the city announced $500 million in investments to: bring long-overdue ADA accessibility to the station, erect two new public plazas, make streetscape improvements, and relocate the Transit Police District 33 station. These investments come on top of the $21.6 million the city committed as part of the East New York Neighborhood Plan to renovate the adjacent Callahan-Kelly Playground, and the roughly $202 million in construction loans that the Leser Group took out to construct 2440 Fulton St., which now houses 1,100 NYC Department Social Services (DSS) employees across the street from the Broadway Junction station.

On top of this, the MTA has secured $2.75 billion as part of their 2025-2029 Capital Plan to construct the Interborough Express (IBX), a new light rail transit line that will run through Broadway Junction on Van Sinderen Avenue. Additionally, an estimated $48.5 million in acquisition and construction loans were assumed by developer Jacob Landau to build 119 units of market rate housing at 2246 Fulton St., just two blocks from the Broadway Junction train station.

Two blocks down, a two-acre multi-building campus is proposed by Brooklyn-based development firm Totem and is currently going through the Uniform Land Use Review (ULURP) process. These private development projects far exceed the amount in public investment that has been made by the city as part of the 2016 neighborhood rezoning approved by Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Considering the flood of private dollars that will continue to inundate Broadway Junction, we are bracing ourselves for a wave of displacement. Property and land values will skyrocket, rents and property taxes will increase, and the area will ultimately become inhabited by a new gentry, pushing out longtime predominantly Black, Latino and South Asian residents who have called this place home. However, there are critical steps the city and state can take to help prevent displacement.

First, the city needs to increase funding for programs such as Partners in Preservation and the Homeowner Helpdesk to support tenant organizing and housing counseling.These were programs that the city baselined and have consistently funded since the East New York Neighborhood Plan of 2016.

The city must also provide property tax reductions or subsidies to homeowners that live in 1-3 family homes within at least a mile radius of Broadway Junction. Cash-strapped homeowners should not face the consequences of being forced to sell their homes because they cannot keep up with the pace of their growing taxes. East Brooklyn has consistently landed on the top of the tax lien sale—we should be undermining that trend, not exacerbating it.

Likewise, the city and state needs to provide universal rent relief to renters that see rent increases within a mile radius of Broadway Junction. The city currently provides rent relief through the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE) and the Disability Rent Increase Exemption (DRIE) programs, and it must design and offer similar programs for New Yorkers within a rezoned area or area experiencing high levels of public and private investment like Broadway Junction.

Lastly, along with these developments, the sudden influx of private capital will drive up property values. This will cause some property owners to “cash-in” and sell their properties to investors who will push out longtime residents to maximize profits. Landlords will be incentivized to remove tenants through buy-outs or abusive tactics, as the area has seen in the lead-up and aftermath of the 2016 rezoning. For this reason, the city needs to expand funding for the Neighborhood Pillars Program to enable CLTs like the East New York Community Land Trust to acquire properties at scale (beyond what the program currently allows) and ensure permanent affordability. che City could even acquire these for-sale properties itself and transfer them to CLTs.

Funding and expanding existing programs, as well as providing universal rent relief to renters and tax relief to homeowners in small homes, should be the anti-displacement policy at the top of the agenda for the city, especially as it relates to Broadway Junction. The days of the city simply providing legal counsel support for tenants within rezoned areas must end.

And to be clear, we are not anti-development or NIMBYs; as a CLT, we are for development that meets the needs of our community members, not development that displaces them. Our elected officials have a choice: be complicit in our displacement or successfully fight for these anti-displacement measures.

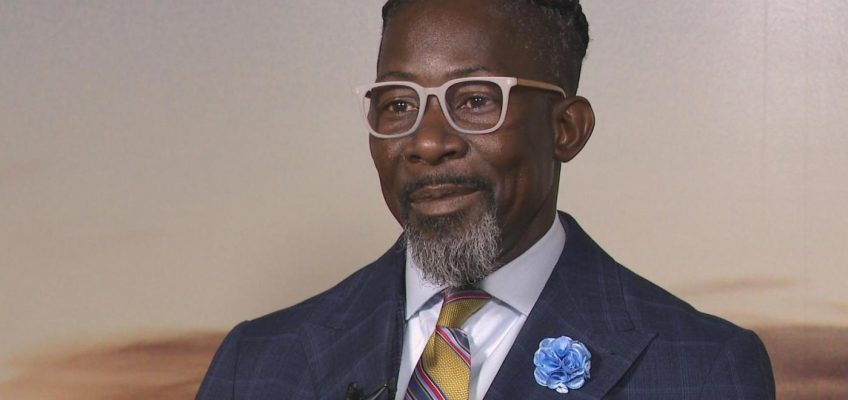

Boris Santos is a public school teacher, East Brooklyn resident, and president of the East New York Community Land Trust.

The post Opinion: Development Without Displacement at Broadway Junction appeared first on City Limits.