Today is Tuesday, Dec. 2, the 336th day of 2025. There are 29 days left in the year.

Today in history:

On Dec. 2, 2015, a couple loyal to the Islamic State group opened fire at a holiday banquet for public employees in San Bernardino, California, killing 14 people and wounding 21 others before dying in a shootout with police.

Also on this date:

In 1804, Napoleon crowned himself emperor of France in a coronation ceremony at Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral.

Related Articles

USA Gymnastics and Olympic sports watchdog failed to stop coach’s sexual abuse, lawsuits alleges

Shooting of National Guard members prompts flurry of US immigration restrictions

US air travelers without REAL IDs will be charged a $45 fee

Here’s why everyone’s talking about a ‘K-shaped’ economy

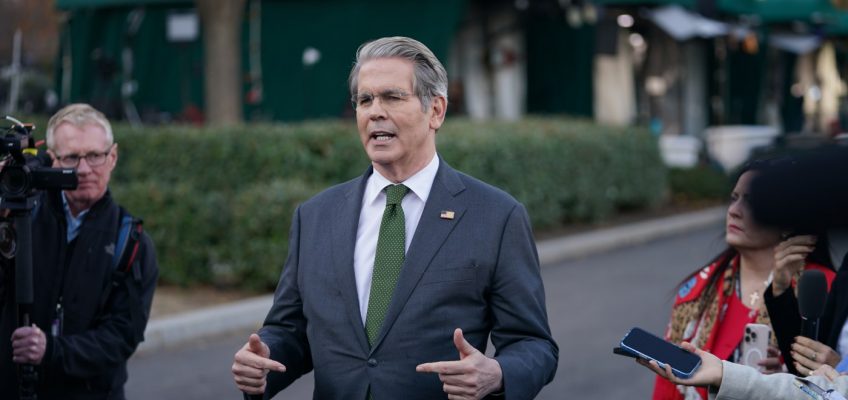

White House says admiral ordered follow-on strike on alleged drug boat, insists attack was lawful

In 1823, President James Monroe outlined his doctrine opposing further European expansion or colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. The Monroe Doctrine effectively created separate spheres of influence for the Americans and Europe.

In 1859, militant abolitionist John Brown was hanged for his raid the previous October on Harpers Ferry in hopes of inciting a large-scale slave rebellion. His execution further exacerbated North-South tensions in the run-up to the American Civil War.

In 1942, an artificially created, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was demonstrated for the first time at the University of Chicago. The experiment led by physicist Enrico Fermi marked the dawn of the Atomic Age.

In 1954, the U.S. Senate, voting 67-22, passed a resolution condemning Republican Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin, saying he had “acted contrary to senatorial ethics and tended to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute.”

In 1982, in the first operation of its kind, doctors at the University of Utah Medical Center implanted a permanent artificial heart in the chest of Barney Clark, a retired dentist who lived 112 days with the device.

In 1993, Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar was shot to death by security forces while trying to flee across rooftops in Medellin (meh-deh-YEEN’).

In 2004, Typhoon Nanmadol lashed the Philippines, killing hundreds of people.

In 2016, a fire raced through an illegally converted warehouse in Oakland, California, during a dance party, killing 36 people.

In 2020, The U.N. Commission on Narcotic Drugs voted to remove cannabis and cannabis resin from a category of the world’s most dangerous drugs, in a step with potential impacts on the global medical marijuana industry.

Today’s Birthdays:

Actor Cathy Lee Crosby is 81.

Film director Penelope Spheeris is 80.

Author T. Coraghessan Boyle is 77.

Actor Dan Butler is 71.

Actor Steven Bauer is 69.

Actor Lucy Liu is 57.

Bassist Nate Mendel (Foo Fighters) is 57.

Rapper Treach (Naughty By Nature) is 55.

Tennis Hall of Famer Monica Seles is 52.

Singer Nelly Furtado is 47.

Pop singer Britney Spears is 44.

Actor-singer Jana Kramer is 42.

Actor Yvonne Orji is 42.

Actor Daniela Ruah is 42.

NFL quarterback Aaron Rodgers is 42.

Actor Alfred Enoch is 37.

Pop singer-songwriter Charlie Puth is 34.