ROCHESTER, Minn. — On a recent Thursday morning at Rochester Public Schools’ CTECH building, high school senior Mazin Bakhit was working on a program he’s been developing for a class project. He’s calling it SharkFin, and it’s supposed to help people improve their financial literacy.

Like students and industry workers, he has been using artificial intelligence to help him with this task.

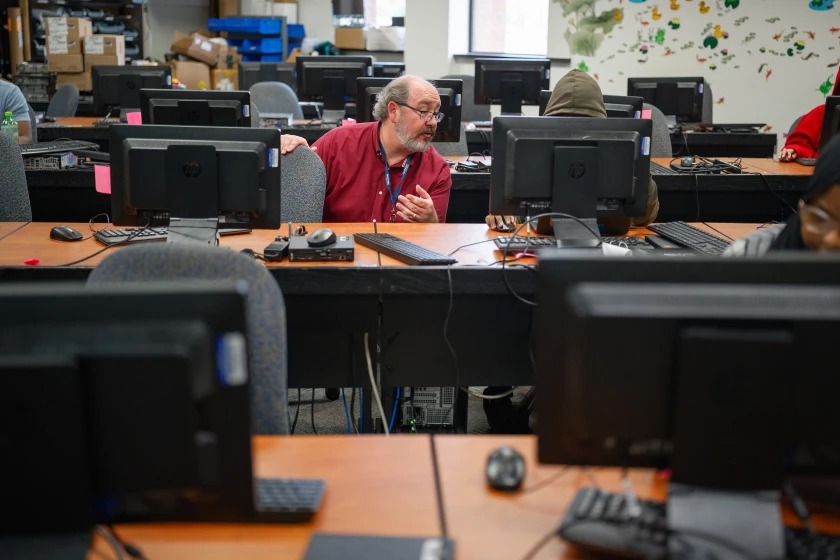

Mazin Bakhit, a John Marshall High School senior, works with Matthew Frazier, an IT and computer science teacher with Rochester Public Schools, on a financial literacy app project for his Computer Science Arts and Labs class Thursday, Oct. 23, 2025, at Rochester Community and Technical College’s Heintz Center in Rochester, Minn. (Joe Ahlquist / Forum News Service)

While developing a part of the program, he’ll run it through an AI platform, and ask the “bot” what it thinks of the product he’s designing. The AI bot will then critique his work, pointing out errors or suggesting improvements that could be made. In turn, Bakhit will tweak his creation and then take it back to the AI bot for further review.

The “two” of them will go back and forth like that, round after round, until Bakhit lands on a version of the program that works best. He says he thinks of AI as “a stingy, mean investor.”

“I say ‘what do you think about this idea?’” Bakhit said. “I’m using it as if I had a feedback coach.”

Bakhit is part of a generation growing up in a rapidly changing technological world. In 2023, the company OpenAI launched the first edition of ChatGPT, which was among the first commonly available AI platforms to hit the market.

And thus the AI revolution launched into full force. Since then, there’s hardly been a segment of life that hasn’t been re-examined through the lens of artificial intelligence.

In Rochester Public Schools, it’s something that everyone’s having to adjust to — from students to teachers to administrators. The goal is not to prohibit students from using it, but rather to help them learn how to use it responsibly, knowing full well that the wider world they are going to enter into after graduation is going to be saturated with it.

That, however, is a bit like building the proverbial airplane mid-flight since the world is still adjusting to what a future under artificial intelligence will look like.

District-wide approach

Earlier this year, RPS Superintendent Kent Pekel suggested the district develop an AI policy during its next strategic plan. After talking to people throughout the city’s schools, he said it became apparent that everyone was approaching the topic slightly differently.

Although it looks like developing a robust approach to AI may take a backseat to other pressing issues as part of the strategic plan, the district is still trying to get a handle on it.

One way it’s done that is by introducing an AI platform called Magic School, which is designed specifically for educators. It’s meant to help them become more efficient, such as using the platform for lesson-planning. The district is piloting the program this year at the four middle schools, with the intent of rolling it out to the wider district after that if it goes well.

And the district is trying to help teachers learn more about artificial intelligence in general. At the beginning of the school year, the district’s AI seminar for teachers was booked solid.

The district has also compiled a list of “guidelines and considerations when using ‘AI’ in RPS,” while acknowledging how fluid the world of artificial intelligence is. The guidelines provide a necessary framework for the district — for educators, support staff and students.

“One of the worst things people in education can do around AI is nothing,” said Naomi Hughes, a library media specialist who works in the district’s middle schools. “Because kids are already using it. And they need skills in order to be able to use it ethically and effectively. So, we can’t ignore it.”

Back to the basics

That doesn’t mean the process of adapting to the new reality has been seamless. Teachers have had to become strategic in order to keep their students in line.

Although part of the district’s adaptation to the AI boom has been to help students learn how to use it effectively and ethically, the wild-west nature of it has sometimes meant that teachers simply need to get back to the basics.

Peter Wruck is the director of research and evidence for Rochester Public Schools, and has been part of the district’s effort to develop a framework for the approach to AI. He noted in a recent presentation that the tools teachers can use to help detect AI in an essay aren’t always reliable.

The presentation cited a few absurd blunders by the programs that were supposed to be able to detect AI-generated work. In one, a program claimed that a section of the Bible was 98.9% AI generated. In another example, three out of four programs claimed with various levels of assurance that the preamble to the Declaration of Independence was AI-generated.

“Their framework was ‘How do I control cheating?’” Wruck said about the teachers who came to the AI training seminar. “And I’m like, ‘To some extent you can’t, unless you change your approach.’”

And that’s just what some teachers have chosen to do.

John Marshall High School English teacher Kristin Welsh uses a software program called “GoGuardian,” which allows her to monitor the screens of all her students in the class.

At any given moment, she can log onto her computer and see what every student is looking at. If they’re playing chess — a popular pastime for students — she can simply close that student’s internet window at a whim.

But despite how many tech-based programs there are for teachers to use, she said that sometimes they simply have to go back to the basics.

“We’ve gone back to a lot of pencil and paper,” she said. “We’ve gone back to timed essays with the onset of ChatGPT and AI … we’ve been going back to our old-school ways, which has really helped.”

The good and the bad

Despite perceptions about how much young people rely on technology, AI does not have a monopoly on the younger generations. According to a September 2024 study published in coordination with the Harvard Graduate School of Education, only 4% of people surveyed between the ages of 14-22 use AI “almost every day or every day.” Another 11% use AI “once or twice per week.”

John Marshall High School English teacher Kristin Welsh speaks with the Rochester (Minn.) School Board on Tuesday, June 3, 2025, about how she has moved to some older forms of schooling due to the prevalence of artificial intelligence. (Jordan Shearer / Forum News Service)

Conversely, as much as 49% of the respondents said they never use AI programs, for a number of different reasons.

That ambiguity among students can be seen playing out in Rochester Public Schools as well. Mayo High School senior Kieran Aganga said that although artificial intelligence has the potential to do a lot of good in the world, it needs to be used very sparingly in light of its environmental impact and the amount of energy needed to power it.

Matthew Frazier is a computer science teacher who worked in the field of technology and artificial intelligence for years getting into education. Although he encourages students — such as Bakhit, who is in one of his classes — to use AI for their projects he estimates that around 10% of his students don’t want to use AI.

“They’re making a moral or ethical decision,” Frazier said about the students who choose not to use AI. “They’re valuing their own learning.”

And that’s partly what underlies the tension between the benefits and problems of using AI. Is it a powerful educational tool that can help students learn when they don’t have someone immediately beside them? Can it be that tool that Dakhit referred to simultaneously as his “stingy mean investor” and his feedback coach?

Or, is there merit to the claim that artificial intelligence is impacting students’ ability to think critically? Aganga described it as a tool that can be useful for helping students understand difficult concepts, but that it’s also a tool that’s just “too easy to reach for.”

The reality is that both those things may be true to some extent.

Mayo High School computer science teacher Eric Dirks says it’s good for students to understand the benefit of the “productive struggle” of learning on their own, but that — at the same time — AI may have its place.

“So many people in the computer science world love solving puzzles. If something else is solving the puzzle for you, it takes a lot of the joy out of it,” Dirks said. “But if you’re sitting at home, and you’re struggling to figure something out, and you don’t have access to the parent or the teacher, then maybe taking it to AI is a good resource.”

The world beyond

But for today’s high school students, thinking about AI goes beyond the classroom. As a generation growing up in the rapidly changing world of artificial intelligence, they’re going to be entering a job market that is changing rapidly.

El Jacobs, a junior at Century High School, works on a coding assignment during a Data Science with Python class Thursday, Oct. 23, 2025, at Rochester Community and Technical College’s Heintz Center in Rochester, Minn. (Joe Ahlquist / Forum News Service)

Unlike former technological revolutions that displaced manual labor, the AI boom has the potential to displace white-collar positions as well, not least of which are the programmers who work in the field of computer science in the first place.

Aganga, the Mayo High School senior, plans on becoming an aerospace engineer one day. And although he doesn’t think artificial intelligence would ever replace the need for human minds in that space, it may take away some of the lower level jobs available, creating more competition for the higher-level positions.

The study from the Harvard Graduate School of Education reported that 41% of “young people believe that generative AI is likely to have both positive and negative impacts on their lives in the next 10 years.”

That was something that resonated with El Jacobs, who’s another one of Frazier’s students in his CTECH class. She described AI as a good learning tool but something that doesn’t belong in creative spaces.

Related Articles

$1B Rosemount aerospace complex, University of St. Thomas semiconductor hub receive state funding

Kevin Frazier: The need to discuss AI with kids

Commentary: Why academic debates about AI mislead lawmakers — and the public

Maureen Dowd: AI will turn on us, inadvertently or nonchalantly

Thomas Friedman: The one danger that should unite the U.S. and China

As for the future, she thinks that although it’s causing some “cultural dissonance” in the immediate sense, AI will have a similar impact that the industrial revolution did. In other words, although there may be some disruption to the job market, there will be other jobs created by it as well.

“I think it’s going to be a good thing in the long run,” Jacobs said.

Leave a Reply