The year Charles Sullivan finally started the treatment that helped manage his agonizing digestive disorder was also the year he was arrested for the crime that would send him to prison for life. Now, 31 years and several surgeries later, he’s still struggling to find relief within the medical system that operates behind Texas prison walls.

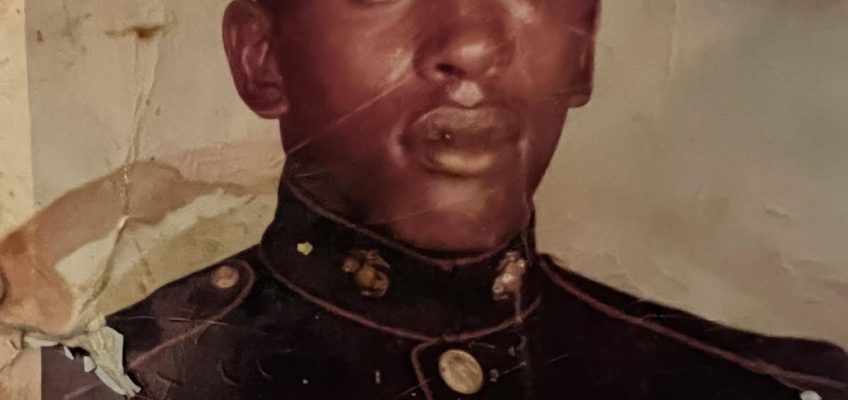

A Marine vet in his early 70s, Sullivan’s health problems began in 1972, more than two decades before he was convicted in Galveston County. He’s been locked up hundreds of miles away from his family since 1994, his kids now raising children of their own. He keeps in touch with them over the phone, doling out what fatherly support he can. Often, they talk about his health.

When he entered the Texas prison system, he was prescribed omeprazole to deal with his gastroesophageal reflux disease. The medication eased his symptoms, which had gotten so bad at times that he’d told his youngest son he felt like he was dying. Even with the meds, Sullivan had a series of operations between 2000 and 2019 that a doctor told him were necessary, Sullivan said, due to damage from caustic stomach acid.

Since 2019, Sullivan, whose life sentence is for capital murder, has been at the 4,500-inmate James V. Allred Unit outside Wichita Falls—nearly 400 miles from his family in Houston. There, last February, a longtime nurse named Joseph Eastridge switched his medication from omeprazole to a drug called famotidine, a different class of drug that’s considered generally less effective for treating Sullivan’s disease. The change was made without warning or explanation, Sullivan said.

Starting on February 25, 2024, Sullivan submitted several written requests to medical staff in his cramped, looping script, asking for the change to be reconsidered. He suspected he was allergic to the new medication; since the switch, he’d experienced chest pain, vomiting, a rapid heartbeat, and other apparent side effects. He asked for his previous medicine and to talk to another nurse or doctor, but he wasn’t seen for nearly two weeks. In the meantime, he submitted a formal grievance to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ), which runs the state’s prisons. In response to his complaints, prison staff assured Sullivan that his medical care was in accordance with policies and suggested he submit additional requests to the clinic if he had any concerns.

By mid-March, Eastridge had reinstated Sullivan’s previous medication—but at half the dose.

Five months later, Eastridge, a 53-year-old certified nurse practitioner, retired from his job at Allred after 23 years, moving to a private clinic nearby. “It wasn’t until Eastridge left that my medication was resumed at the proper effective dosage of twice a day,” Sullivan wrote the Texas Observer over a prison messaging app this May.

Sullivan is one of more than a dozen people—current and former Allred prisoners and their family members—who have spoken or written to the Observer since last spring about alleged mistreatment or lack of medical care at the Wichita Falls-area prison, one of the largest in Texas. Most of the complaints centered on Eastridge, who, according to the prisoners and family members and to allegations in more than 20 federal lawsuits filed since 2002: withheld or cut off access to medication or equipment, including bandages and braces, even if the prisoner had had access to the items for decades; told prisoners that their conditions, ranging from debilitating back pain to diarrhea, were fake or “normal”; refused to write passes for people with injuries or disabilities to keep them in bottom bunks; and allegedly retaliated against those who filed grievances by removing access to meds.

Charles Sullivan joined the U.S. Marine Corps in the early 1970s and served as a combat engineer. (Courtesy/Verchon Sullivan)

One man, who sued in 2002, claimed Eastridge had “aggressively” forced a hose down his throat when pumping his stomach after guards suspected he’d overdosed on his hypertension medication. In the suit, the man alleges that Eastridge said, “Seeing how you ruined my day, I am going to enjoy shoving the ‘garden hose’ down your throat.” (A judge dismissed the case, writing that the complaint was “nothing more than a disagreement over the emergency medical treatment.”)

Eastridge, who currently works as a nurse practitioner at the Clinics of North Texas, did not reply to repeated Observer requests—via phone, mailed letters, and an attempt to reach him through his employer—for an interview or comment for this story.

A Texas Tech University employee during his time at Allred, part of a state-university partnership system, Eastridge prescribed meds and treated thousands of patients from 2000 to 2024.

For this story, three experts reviewed the allegations that prisoners have made against Eastridge. One told the Observer that some of the contested decisions could have been reasonable medical calls required by prison or university policies, while others raised red flags.

“There are some things in there that are the kinds of complaints you see all the time, even about good practitioners,” said Marc Stern, a former medical director of Washington state’s prison system and current court-appointed monitor of Arizona’s prison medical system. “But the weight of all of it, of so many complaints about one person, is certainly a reason to look further.”

Nursing expert Angela Clark, a University of Texas at Austin professor emeritus who’s testified in court about medical conditions in correctional settings, said the allegations “show a pattern of not meeting expected national standards for advanced practice nursing in a correctional setting.” She said that some allegations—withholding seizure medication, not facilitating a bottom-bunk bed for a one-armed man, and treating patients with hostility—were “especially troubling.” But, she noted, without additional evidence, some claims could be a matter of patient perception rather than wrongdoing.

While it’s notable for one medical professional to face such a barrage of complaints, Brian Nam-Sonenstein, senior editor and researcher with the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative, said these types of allegations are “par for the course in prisons, not just in Texas but everywhere.”

He told the Observer that incarcerated patients routinely struggle for even the most basic medical help. “This extends beyond more-serious cases where someone is in obvious, serious need of lifesaving treatments. If you can’t even get something like Tylenol without putting up a protracted fight, that disciplines people and sets expectations pretty low.”

Amanda Hernandez, director of communications for TDCJ, told the Observer in an email: “All medical decisions are based on the individual medical needs of each patient.” Hernandez did not address the specific allegations against Eastridge when presented with them—instead referring the Observer to Texas Tech—and stated that her agency does not monitor lawsuits against university staff, like Eastridge, adding that there have been no sustained internal complaints against the nurse practitioner.

Medical grievances against university employees are handled by the university and sent to a division of TDCJ if appealed, according to Hernandez. Suzanna Cisneros, director of media relations for the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC), Eastridge’s former employer, responded to an Observer email requesting an interview with the agency’s leaders: “Regarding access to medications and medical supplies, all medical decisions are based upon clinical indication. All complaints are fully and thoroughly investigated by TTUHSC.” Cisneros did not respond to an email detailing specific allegations against Eastridge.

Most of the lawsuits against Eastridge were dismissed before he or lawyers for the state responded. In one 2020 case (dismissed in 2022) where state attorneys did respond, they denied any wrongdoing, disputing a prisoner’s allegation that Eastridge had not properly treated a broken knuckle. “At all times relevant to this cause, [Eastridge] acted … with the reasonable and good faith belief that his actions were proper under the Constitution and laws of the state.” The Texas Board of Nursing, the relevant state licensing agency, has never disciplined Eastridge, but the board would not provide information about any complaints submitted by patients, citing confidentiality laws.

Ostensibly, medical care in American prisons should look just like medical care offered outside prisons. But decades of litigation and scandals have shown that correctional healthcare occupies a space wholly its own. Issues of funding, security, staffing, and bias all complicate the provision of care behind bars.

The Allred Unit utilizes just 64 medical employees to run its 24/7 care. Like other units, it’s also been continuously short-staffed in recent years, with just over half of correctional officer positions filled as of the end of 2023. The lack of guards can affect medical care: One prisoner reported missing appointments because staff didn’t provide the necessary passes to leave the housing area. On more than one occasion, records show that appointments were cancelled because of lockdowns or a lack of personnel. The Observer also verified that, at least once in 2024, a diabetic prisoner did not get a scheduled test because of insufficient nursing staff.

Family members and outside advocates have no direct line to medical providers at Texas prisons. Instead, they’re routed to the unit medical administrator, who they say rarely responds, or to family liaisons, who reportedly aren’t always receptive or forthcoming. Prisoners don’t have the freedom to get second opinions or switch providers if they disagree with a diagnosis or treatment and often aren’t given rationales for medical decisions. To access their own medical records, they have to pay 10 cents per page, which can add up if requesting multiple years’ worth of documents. In a state where prisoners are not paid for their labor, this means records are out of reach for many.

And, as the fate of complaints about Eastridge highlights, there are few paths to possible accountability for alleged bad actors in this underfunded system. All lawsuits against the longtime nurse were dismissed, most either for technical reasons such as missed deadlines or fees or for not clearing the extremely high bar for a federal civil rights complaint.

One of Sullivan’s sons, Verchon, lives with severe acid reflux symptoms similar to those of his father, which has made him acutely empathetic to his dad’s suffering. “There were times where I didn’t get my medicine on time, and it was the worst couple days for me,” he told the Observer in an interview.

Over time, frustration with the system gave way to a feeling of helplessness. His father left when Verchon was young: In his memory, his dad is a giant; in reality, he’s shorter than Verchon. His dad also doesn’t seem so big compared with the seemingly unreachable officials who run medical care in Texas prisons.

“His custody and care is in y’all’s hands,” Verchon said. “This is a person who’s crying and screaming about their medical issues and needs, and it’s being overlooked.”

Until the 1990s, TDCJ directly ran the medical care in its facilities. But it became clear something had to give: Starting in 1980, the system was put under federal oversight in part because of shoddy medical treatment exposed by a successful prisoner lawsuit. Then, through the 1990s, Texas’ prison population surged.

In 1993, state lawmakers concocted a partnership between the prison system and public universities, meant to put medical responsibilities in the hands of people better-suited to the task. This ostensibly made the whole operation more cost-effective as well, attractive both to lawmakers and taxpayers. The University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) and TTUHSC would each take partial responsibility for the medical care of the state’s roughly 64,000 prisoners (today, that number has more than doubled). UTMB covered about 80 percent of the population and TTUHSC the remaining 20, including those at the Allred Unit.

The partnership was written into law, with the finer points being managed by annual contracts between TDCJ and the universities. The prisons would provide the infrastructure: space, maintenance, administrative support, and funding from the Legislature. The universities would be left to focus on providing the actual care: hiring staff to diagnose and treat patients. After less than a decade, the new system seemed to be working. In 1999, federal oversight of medical care officially ended.

Texas’ setup is often lauded as a viable alternative to private medical contractors, which are commonly used in other states and are notorious for prioritizing profits at the expense of patients. But public partnerships don’t cure all ills, experts say.

“Public providers face some of the same constraints as private ones: both are at the mercy of limited budgets and operate within the corrections hierarchy, where healthcare decisions take a backseat to security and the orderly operations of corrections facilities,” Nam-Sonenstein wrote in a recent nationwide report.

“THE CONSTITUTION DOESN’T PROTECT YOU FROM BAD MEDICAL CARE OR STUPID MEDICAL CARE.”

Notably, correctional facilities are the only places in America where individuals have a federal constitutional right to medical care. That’s because, in 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that deprivation of medical care in prisons and jails could violate the Eighth Amendment prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishment.” States are on the hook for funding this care without help from federal subsidies like Medicare or Medicaid: Eligible prisoners can enroll in Medicare, but the funding won’t be provided while they’re still incarcerated, and incarceration makes them ineligible for Medicaid. So, in many places including Texas, cost-cutting is a major priority. The Correctional Managed Health Care Committee, a body including governor appointees and the presidents of TTUHSC and UTMB which oversees the Lone Star State’s university-partnership system, is required along with TDCJ to submit annual reports on savings efforts to the Legislative Budget Board and the governor’s office.

A 2017 Pew report showed that Texas spent below the national median on annual healthcare for each prisoner. Still, the bill is high: Texas budgeted more than $767 million for prison medical care in 2024. And expenses are growing as medical costs rise nationwide and as Texas’ prison population gets older. According to its most recent legislative budget request, TDCJ needed more than $100 million in additional funding for the upcoming fiscal year just to keep up with costs while maintaining the same level of care. The price to replace aging medical equipment and of staff salaries is rising too. All this adds up to a big budgetary demand.

State law also requires TDCJ and the contracted universities to monitor care and report to both the state oversight committee and the Texas Board of Criminal Justice, a governor-appointed body over TDCJ. The last report on medical care at the Allred Unit is from September 2022; the prison received a compliance score of 82 percent for the general population, a term referring to the vast majority of prisoners who haven’t been placed in special housing for their medical needs or security reasons. The brief report, obtained by the Observer through an open records request, shows that the unit’s preventive and follow-up care for conditions including tuberculosis, hepatitis B, and sexually transmitted diseases was lacking. The unit also fell short on nursing metrics, including documentation requirements and physical exams for older prisoners. The audit made no mention of the dozens of lawsuits and other grievances against one of the unit’s nurse practitioners.

When asked whether contract monitors had ever found cause for concern at the Allred Unit, Hernandez told the Observer, “TDCJ is committed to ensuring that all incarcerated individuals, including those at the Allred Unit, receive adequate health care. As part of this commitment, contract monitors regularly evaluate services to identify areas for improvement. When findings occur, TDCJ works closely with TTUHSC to address concerns promptly and implement corrective measures.”

Robert Greenberg, chair of the Correctional Managed Health Care Committee, said via email: “The Correctional Managed Health Care Committee does not oversee the day-to-day medical operations at TDCJ units nor the delivery of direct patient care services. Those responsibilities rest with the university health care providers.”

In 2013, Leonel Chavez Jr. filed a far-reaching federal civil rights lawsuit against TTUHSC, TDCJ, and individuals including Eastridge at three units where he’d been held.

In 2008, the then-39-year-old had injured his back while working in the laundry room at the Smith Unit, located in West Texas between Lubbock and Odessa, resulting in a herniated disc. After that incident, Chavez wrote in the lawsuit, which he filed without a lawyer, that he “was denied proper medical treatment & diagnosis, & denied any form of medication for the pain.” He said unit and medical staff did not believe he was actually in pain, even though at times it was so severe he would pass out and his breathing would become so labored he felt as if he “was having a heart attack.”

Chavez, a Rockwall native who was nearing possible parole, was moved to Allred in 2012 after he’d requested a hardship transfer. He wanted to be closer to family in North Texas. There, the pain continued.

“When I get to Allred, my back is killing me,” he later told the Observer in an interview. At the time of his transfer, he’d already been through three back surgeries during his incarceration.

Then, he encountered Eastridge, who had been promoted from charge nurse to what’s called a physician extender, taking on responsibilities that might typically be handled by a doctor. Eastridge immediately reduced his pain medication, Chavez said, prescribing him 500-milligram doses of ibuprofen—just slightly over the normal dose recommended for adults. “I pleaded with him to not do so, because of all the pain I have to go through on a constant daily basis,” Chavez wrote in the lawsuit.

Eastridge allegedly “provided nothing more than counseling of exercising, reduction of pain medications, the dangers of drug usage for an extended basis. … Eastridge refused to pull up Chavez’s medical history records and properly review and evaluate his complained of problems,” according to the suit. Eastridge allegedly insisted Chavez go on an antidepressant and diagnosed Chavez as “feigning illness.”

On September 25, 2012, Chavez saw Eastridge again to request medication for his back pain, per the suit, and Eastridge repeated that Chavez was faking his pain, “even after reading Chavez’s medical chart, MRIs, x-rays, and the extensive informative chart notes written by the neurosurgeon and other qualified doctors.”

Eastridge then took Chavez off all his pain medication, Chavez said in the complaint, which he filed at that point in a bid to put his experience on record. “It’s above Eastridge. Eastridge has a boss,” Chavez, now a straight-talking grandfather and a free man since 2014, told the Observer in a May interview at a North Texas steak house. “The head of the department for TDCJ, they got guidelines. … The worst scenario possible that Eastridge might get?” he said, slapping himself on the wrist to demonstrate.

In a rare show of formal support in these types of cases, Chavez’s wife and two sons joined the lawsuit as co-plaintiffs, citing the mental distress and financial hardship the situation had caused the family. In the suit, they said they were treated with “retaliatory, harassing and threatening” responses when they called the units about Chavez’s health problems.

But, in January 2015, a judge dismissed Chavez’s claims, noting that he and his family “understandably have experienced frustration as a result of the complications in Leonel’s medical condition.” Even so, the judge found that the complaint didn’t meet the criteria of a federal civil rights claim—the primary legal path for prisoners to get their complaints before a judge at all—which the U.S. Supreme Court has said requires showing that a medical official exhibited “deliberate indifference to serious medical needs of prisoners.”

Examples of health-related items that have been taken away from or denied to prisoners (Ivan Armando Flores/Texas Observer)

Even though TDCJ prisoners are in state custody, attorneys told the Observer that the Texas Supreme Court has essentially walled off the state courts to medical negligence claims from incarcerated litigants against providers. Their only hope often lies in a Reconstruction-era snippet of federal civil rights law that allows litigation over violations of an individual’s U.S. constitutional guarantees, such as the ban on “cruel and unusual punishment.” Though uncommon, federal courts can force state prisons to change unconstitutional behaviors.

Chavez was one of many Allred prisoners who turned to the courts when complaints filed to prison officials went nowhere: Eastridge was named in at least 21 federal lawsuits across his tenure at the Allred Unit—the first in 2002 and the latest filed this year—during which time he worked as a licensed vocational nurse, a correctional nurse, a charge nurse, a physician extender, and an advanced practice provider. Eastridge got his nursing degrees at Texas Woman’s University and West Texas A&M.

In these suits, former patients allege Eastridge’s behavior and decisions led to a wide range of problems. The claims range from denial of seizure meds to withdrawal of disability accommodations to the allegedly aggressive stomach-pumping incident.

None of the lawsuits resulted in any court-mandated change. Most were dismissed for not reaching federal standards, for being filed after the statute of limitations expired, or because the prisoner had already filed too many other lawsuits. In a 2023 dismissal order for one of the cases, a judge wrote that “A disagreement over a medical care provider’s assessment of a patient’s physical condition and the need for treatment, if any, does not rise to the level of a constitutional violation.”

Such outcomes are the norm for legal attempts to force improvements to prison healthcare.

A March 2023 article in the New England Journal of Medicine highlighted the barriers incarcerated people face when trying to sue over medical care, noting that “rare wins yield only incremental relief.” And to even file their long-shot federal claims, they must navigate the Prison Litigation Reform Act of 1996, which forces prisoners to exhaust lengthy state grievance processes before suing and makes it harder and costlier for prisoners to succeed.

Prison lawsuits are also likely to bepro se, meaning prisoners are representing themselves. Research shows that pro secivil rights cases by incarcerated people are successful only 6 percent of the time.

In 2017, Austin civil rights attorney Jeff Edwards helped represent a group of prisoners with hepatitis C in a successful civil rights lawsuit over Texas prison medical care. As part of a settlement, the court ordered a timeline by which the prison had to provide proper antiviral treatment, which the patients had not been receiving. Edwards said the cases his firm has handled on behalf of Texas prisoners are taken more seriously by the courts because of the professional legal representation, “unfair as it might be.”

The legal bar Edwards had to clear was extremely high, he said. Negligence, poor decision-making, or other forms of frustrating medical care aren’t enough. “The Constitution doesn’t protect you from bad medical care or stupid medical care,” he told the Observer.

Although TDCJ said it doesn’t monitor lawsuits against university medical staff, the contract between the agency and Texas Tech does stipulate that the entities must work together to resolve lawsuits related to medical care “in a manner that best serves the mutual interests of the TDCJ, the TTUHSC, and the State of Texas.”

A few months before his lawsuit was dismissed, Chavez was released from TDCJ custody, having spent more than a third of his life behind bars. Since then, he’s seen several doctors and received follow-up surgery on his back. More than a decade later, it’s still painful just to walk.

Felicia Roadifer lives with her husband in Fort Worth, more than a hundred miles south of the Allred Unit, where her dad has been held since 1996. Roadifer’s parents have both been imprisoned since she was a teenager, and she said she talks to them on a regular basis, trying to keep up with how they’re doing.

While her mom has other family in the state, Roadifer said she’s her dad’s only lifeline.

Since her father had a heart attack in 2022, she’s had to call the unit numerous times because he said he was having trouble getting his medication, was not being taken to the clinic for appointments, and was waiting months to get the physical therapy he was supposed to receive after his bypass surgery, she told the Observer.

“I’ve had to call up there at the unit and talk to the warden’s secretary, talk to the warden, and everything else like that just to get them to do something about my dad,” Roadifer said.

Family members and outside advocates often feel they have to intervene on a prisoner’s behalf when an incarcerated patient reports that their concerns aren’t being heard. Many inside prison don’t have outside connections to step in for them. Roadifer said she’s even contacted the unit about other people’s medical care that her dad told her about.

“Oftentimes, it comes down to: Do you know the right person? Do you have somebody on the outside who has the time? … Have they sort of built a relationship with the one person who’s in the office three days a week?” Nam-Sonenstein, the prison policy researcher, told the Observer.

One prisoner at Allred—who prefers they/them pronouns and asked not to be named for fear of retaliation from prison staff—has leaned heavily on outside advocacy. They told the Observer they’ve used a CPAP machine for sleep apnea since 2017. In November 2019, they asked Eastridge to slightly increase their prescription for distilled water, which the machine needed to function. They had a prescription for a gallon a month, but the machine was using that much in three weeks. Eastridge, instead of approving more distilled water, told them to stop using their machine for a week each month, they said, even though that would worsen their symptoms and endanger their health.

They complained about Eastridge’s decision to the unit medical administrator, Texas Tech, and the Texas Board of Nursing. But they got no substantive response, they said.

In a separate incident last year, the same prisoner said they were told they couldn’t get their diabetes medication—metformin, atorvastatin, and lisinopril, which they had been taking since 2017—because they hadn’t been seen for a checkup appointment, even though records show they’d seen a provider for that exam just a month prior. The prisoner recalls being shown a computer screen that noted Eastridge had denied the refill, but records reviewed by the Observer indicate it was another nurse who’d made the decision to renew the meds for a month rather than the usual year. It was now two days before they would run out of the meds. At this point, their spouse on the outside contacted Texas Tech, the family hotline, the unit warden, and the medical administrator.

“I literally got stress hives,” said the partner, who asked not to be named to maintain the prisoner’s anonymity. Like other loved ones of those incarcerated in Texas, the partner cast a wide net, hoping to get lucky by looping in people who might have some sway. The prisoner finally got their prescriptions on time—after days of panicked outreach.

For many, this process feels like shouting into a void: sending requests for medical visits every day that come back marked “do not schedule,” describing pain and discomfort but not being believed, trying to stay healthy within a system to which you have no alternative. These experiences are not unique to Allred. Across the enormous Texas prison system, despite having a less profit-driven model than those of some other states, medical care remains underfunded, understaffed, and underprioritized. The case of Eastridge is noteworthy for the number of complaints over his long tenure, but the bulk of the state’s more than 130,000 prisoners live at constant risk of falling through a system whose cracks are larger than its footholds.

Verchon, Sullivan’s son, told the Observer that his dad’s medical care improved after Eastridge left last year, but the broader culture didn’t change much. He said it’s hard to hear about his dad suffering six hours away from home. Sullivan’s family is trying to get their father transferred to a closer unit, where the medical care might be better and where it will be easier to visit. Another of Sullivan’s sons, Dramond, has terminal cancer, and Sullivan, who has little realistic chance at parole, has only so many years left. His time at Allred has worn him down, from the towering figure of his son’s memory to someone who has to beg for help. He’s not frustrated or bitter; he’s just in pain.

“You can hear the hurt,” Verchon said. “Nobody, no matter what you’ve done, should be treated like this.”

The post The Health Penalty appeared first on The Texas Observer.

Leave a Reply