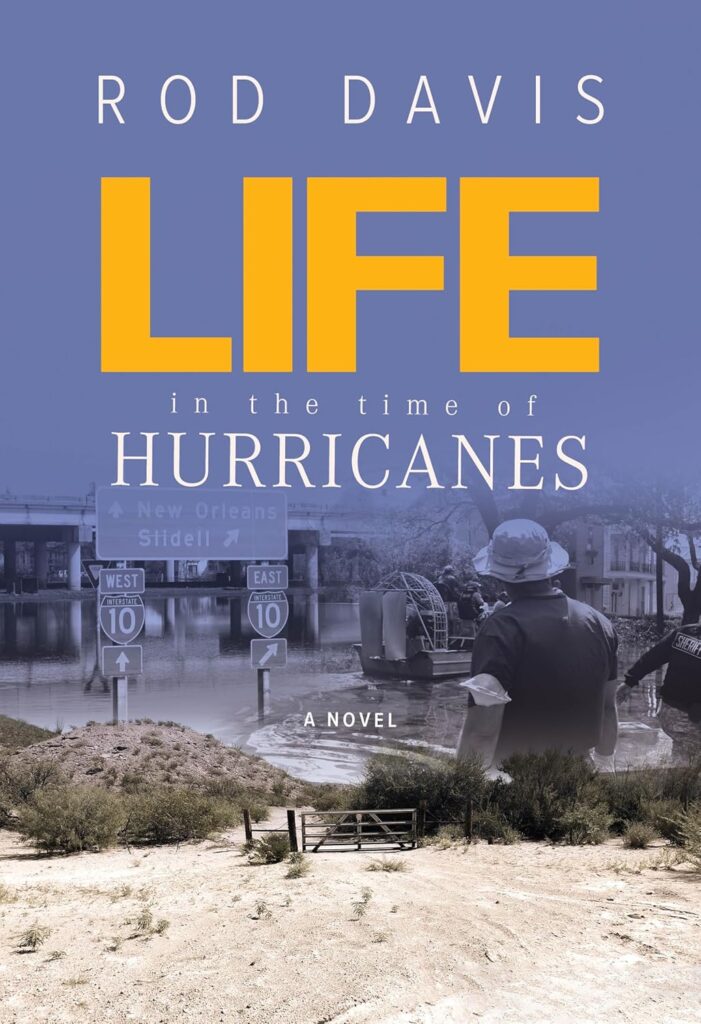

Editor’s Note: The following is excerpted from the first chapter of Life in the Time of Hurricanes by Rod Davis, out this month from TCU Press. It is republished here with permission.

“And once the storm is over you won’t remember how you made it through, how you managed to survive. You won’t even be sure, in fact, whether the storm is really over. But one thing is certain. When you come out of the storm you won’t be the same person who walked in. That’s what this storm’s all about.”—Haruki Murakami, Kafka on the Shore

Tuesday, August 23

From the fresh gravel path on the Moon Walk atop the ancient city’s levee, Duane McGuane watched the early-morning produce trucks clump around the French Market below. Drunks and derelicts that had survived another night mingled among the rigs like vampires. He wanted them all to go home. They never did. He turned to face the river. A grayish cast to the far horizon meant storm clouds were piling up out in the Gulf, and the Mississippi already had begun to moan. The crescent that gave the city its nickname was full of gambling barges and tankers, and it wouldn’t be long until they were dispatched seaward or secured down on the docks of the river and the bayous. Early wind gusts churned the waters. Flashes of sun sparkled green, purple, and gold on choppy slicks of oil. In them, Duane saw Mardi Gras and king cakes and the tattoo on Maybelle’s back. His focus refixed itself upon one of the ferries that ran back and forth day after day from Algiers Point to Canal Street. He watched it a long time. He felt very serene.

In that moment, that precise, discrete temporal demarcation, Duane saw what was to come—the great movement, the urge of migration he knew was the lot of his species and not just his personal burden. He heard the voice come from inside, and it was that of a great fierce dog atop a jagged boulder in the Himalayas howling of distant chaos. The howl was like a marvelous force inside his entire head and body and no one knew of it. But he did, and it had breached his world and he was going where it led.

A burst of wind blew bits of earth and litter across his cheek. Duane brushed his face and looked out to the southeast. So late in the season, this was likely a bad one, if it came this way. He turned his back to the river to face the city again; the place he loved, hated, exalted, and reviled. He pondered otra vez the aforementioned produce trucks and drunks, and now also from the corner of his vision a Vietnamese waitress in black pants and white shirt at Café du Monde shaking out a tablecloth on the sidewalk below. Also, in that exact second, he watched, from another angle still, his entire being as if viewed from the heavens, poised neatly on the Moon Walk, the impetuous idea of jumping into Old Man River just to see if he could survive the strong current having passed and morphing into something much finer.

Thus now did he see his new life, all at once and stretched out to infinity, and in that spectacle did Duane McGuane join the ranks of the prophets, and he had in mind a certain redoubt in Texas. From there they would begin it all, the fierce, stray, lost dogs of his acquaintance and yet of his fortune to come. They would howl from within that place where they would no longer have to deal with any of this shit.

Maybelle woke up from her nap later than usual, which meant she would be later than usual to work, a bent toward tardiness that disturbed her less than it might in others more inclined to guilt. You could include her boss in that latter conglomerate of sad and desperate clock-watchers. Also she could be cranky. Part of her wanted Arturo to just fire her and be done with it. But the part of her that didn’t—that saw getting fired as the first stage in a domino progression that led to getting bounced from her duplex and sundry other privations of unemployment—made her bolt upright from bed, shake her head once to kick the gears into motion, and proceed with her ablutions.

When that was done and a rice cake and Community coffee in her stomach, she blew out the door and hurried to her old Toyota on the narrow street of small brick houses about a half step ahead of receivership. Most of the houses didn’t have garages, so all the cars were crammed together on the curb, and it took her a good five minutes to wheedle herself free of the cramped space defined in front by an old Caddy and in back by a Dodge van with a bondo-packed fender. Except for the weather, it was looking like “just another day,” as that Paul McCartney song went, for the best waitress at Arturo’s, “the finest restaurant in the Irish Channel,” as Arturo’s ads went, no sense of irony at all in that man.

But she tried not to fault him any more than he deserved. Her own shortcomings were her long-term future, as her mother had put it. Maybelle herself had a sense of irony—but those were hard words nonetheless. We didn’t send you to Tulane to be a waitress or work in a department store or clerk for those communist lawyers in Baton Rouge was the rest of her mother’s verdict. The response—Then what did you send me to Tulane for?—was no longer answered, only sighed upon. But the department store wasn’t bad, the argument usually went, because it was an entry point to becoming a buyer and then a ladder into management, which of course was what a degree from Tulane was for. That and marrying the right boy so she could settle in over by Audubon Park on Henry Clay or maybe even St. Charles. Which scenario her mother always duly denied, thus confirming it as truth. They never even talked about the storefront poverty law center work two years ago and all that had ensued from that. Sometimes Maybelle did think upon it herself, and every so often she drove up the River Road, the slow way, to William’s grave and left some flowers, for him, for them. But that seemed long ago and a certain amount of regrouping was in order.

She went into the back of the restaurant and took off her summer smock and put on the black shift and low-heeled shoes of her station. She didn’t really have a locker, just a hook on the wall on which to hang her stuff. A hooker, she frequently said to herself long after the joke had gone flat. Her purse went under the cash register out front, where she could keep an eye on it. As she disrobed, Benny, the other waiter for the night, unless it got busy, came in. He already had on his white shirt and dark pants, but they had changed in front of each other before and it didn’t matter because he was gay, but in truth Maybelle wouldn’t have cared anyway. Sexual interludes were far from her mind. And her, thirty-three years old!

It wasn’t yet five, and a Tuesday, so nobody had come in, not even the early conventioneers. Benny went around fixing and fussing at the dozen tables in the dining room. Bertie, the creepy guy from New Zealand, cleaned off the marble counter in the long, dark bar and lined up the glasses hanging upside down overhead. He would get the first wave of customers, and he would lubricate them.

Maybelle waited for the onslaught in a high-backed, lacquered wooden chair against the wall, under a print from the South of France. She looked out the window toward the street, and at the parking lot on the other side next to the corner grocery. Two beige sedans with Avis stickers on the back slowed and pulled tentatively into the lot.

Four men got out of one car and four women out of the other, all dressed in suits or the equivalent, and rejoined each other, stiffly, then came across the street.

Seeing them, Bertie yelled to Lisa, the main bar waitress, to get some ice, and in came the people, their convention badges still hanging from cords around their necks. Maybelle had a theory about that, that people kept the name tags not because they had forgotten to remove them but because in an alien city it reminded them who they were. Maybelle knew how easily that could be forgotten. How easily anything could be forgotten if you put your mind to it.

The post Life in the Time of Hurricanes appeared first on The Texas Observer.

Leave a Reply