“Everything collapses in the ripping sound of great manifestations,” wrote Suzanne Césaire in 1945. The line purportedly described an immense hurricane in the Caribbean Sea, but knowing Césaire—a formidable theorist, postcolonial and feminist activist, and surrealist from Martinique—“great manifestations” also referred to seismic shifts in history and decolonization. A critic who wrote with the revolutionary force of manifestos and the wisdom of the longue durée, Césaire published in the short-lived literary journal Tropiques, which she established with her husband in 1941 and co-edited. There appeared the only seven essays she ever completed. After 1945, she would not publish again.

Due to her relatively small body of work, as well as societal misogyny then and now, Césaire’s legacy is often overshadowed by that of her husband, Aimé Césaire. Award-winning poet, former president of the Regional Council of Martinique, and mayor of Fort-de-France for 56 years, Aimé is an icon of postcolonial politics and Francophone literature. He published many books, such as Discourse on Colonialism, and is memorialized across France, Martinique, and elsewhere. Still, even with no clear answer to the question of why Suzanne Césaire stopped writing, her contributions have become seminal texts in surrealist, feminist, and communist movements, especially those rooted in Black and anticolonial struggles.

Two offerings in the Dallas-Fort Worth area are a testament to the small but sure renaissance of Césaire’s legacy. In 2024, María Elena Ortiz, curator at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, organized the exhibition Surrealism and Us: Caribbean and African Diasporic Artists since 1940, named after Césaire’s essay, “1943: Surrealism and Us.” This summer in Dallas, artist Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich will screen her new film, an experimental take on a biopic, The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire. Ortiz and Hunt-Ehrlich, friends and collaborators, are making an important revision to our historical record and proposing profound questions about nature, fascism, race, and gender from the Caribbean to Europe to the United States.

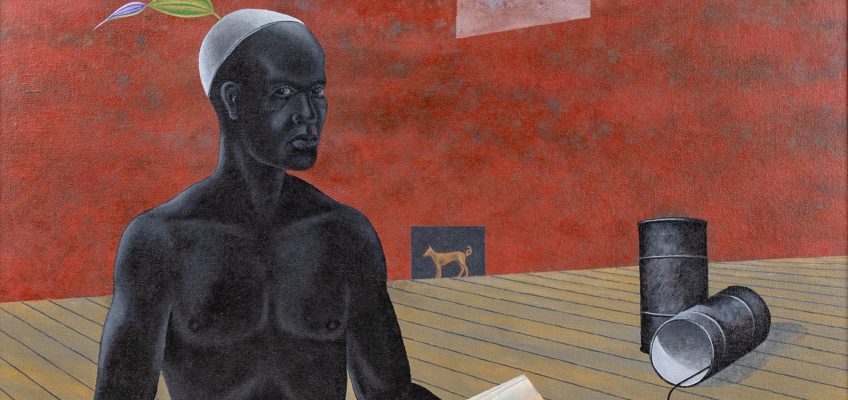

There is a Meeting Here Tonight: Election Results (Stanley Greaves)

From March to July 2024, the Modern’s Surrealism and Us exhibition displayed 80 artworks at the intersection of Caribbean aesthetics, Afrosurrealism, and Afrofuturism. Works included 1940s Cubist paintings by Cuban artist Wifredo Lam; 1950s paintings of colorful, erotic shapes by Dominican artist Cossette Zeno; collaborative exquisite corpse drawings by 1970s surrealists; and contemporary video, installation, paintings, and sculptural work by American artists Arthur Jafa, Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, and Simone Leigh. Essays in the exhibition catalogue explore Afrofuturism and Afrosurrealism in American popular culture today, pointing to musicians and filmmakers such as Janelle Monáe, Jordan Peele, and Boots Riley. As Ortiz writes, “The conditions of Black life, in the Caribbean and America, have become ever more viscerally surreal.”

Ortiz planned the exhibition to emphasize themes such as “the marvelous,” a concept developed by Césaire that referred to a state of mind in which colonized people can access their unconscious minds to question colonial oppression. In wall text and in the catalogue, Ortiz encourages spectators to consider Haiti in particular, drawing attention to the Haitian Revolution, which was catalyzed by a Vodou ceremony. The writings of Césaire and Ortiz both tell the story of surrealism from a Caribbean perspective, a departure from the dominant art historical focus on French surrealism. As they explain it, surrealism was not merely a French art movement that made its way to the Caribbean. Rather, surrealistic thinking was a mode people in the Caribbean, particularly those in the African diaspora, had already been using for centuries to imagine realities beyond their present conditions.

Compared to a large museum exhibition, Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich’s film, The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire—a visually stunning, intriguing, and conceptual project—zooms in more closely on Césaire as an individual figure. Filmed at a lush tree archive in South Florida resembling the flora and waterways of Caribbean jungles, Ballad’s defining feature is regular voice-overs read by actors playing Suzanne and Aimé, drawn from Suzanne’s writings and texts written about her. The film deconstructs the biopic genre by making transparent the production and performances that go into a film—by including shots of the crew and details of the set and by exposing the interpretive work of actors. Zita Hanrot and Motell Gyn Foster, playing the central couple, discuss on camera their speculations about what may have been going on inside the Césaires’ complicated marriage and why Suzanne may have stopped writing. They reenact scenes from the couple’s lives, such as radio appearances or dance sequences, but often they simply walk around, read archival papers, or speak directly to the viewer. Their role is not so much to act as the Césaires as to ambiguously stand in for them or explicitly play themselves. We are invited into the complex work of actors, people sincerely engaged in a mysterious ritual of remembrance.

This is a fitting tribute to Suzanne Césaire’s elusive legacy, as what remains of her is a memory as pieced-together, fragmented, and dreamlike as the art she studied. Hanrot was three months postpartum at the time of filming, and the burdens of motherhood are named as one reason Césaire may have stopped publishing: “It is difficult to be a productive writer when you have six children.” Hunt-Ehrlich has written that she makes work “concerned with the inner worlds of Black women,” and Ballad, without assuming what Césaire’s inner world consisted of, takes seriously the fact of it. Interwoven through the film are scenes of pieces of paper, implied to be Césaire’s discarded drafts, in varying states of precarity or decay: sheets flying in the wind off the back of a truck on set, floating in a pond rippled by fish below, covered in ants, burning in a campfire, or found by a camera assistant by chance.

In its hazy reenactments of the 1940s, Ballad lingers on the historical conditions that Césaire wrote within: the Vichy control of Martinique. The first time we see Hanrot as Césaire, she is lost in thought smoking a cigarette in a Martinican lounge amid the threatening presence of a French soldier, with jazz playing on a victrola and the French flag hung between palms. Voice-overs describe how authorities attempted to shut down Tropiques, the Césaires’ literary magazine, in the context of escalated white supremacist governance and fascist purges of Martinican political prisoners. In moments like these, Ballad feels instructive for American artists and writers living through times of rising fascism, censorship, and deportations. The renaissance of Suzanne Césaire’s work in U.S. circles seems likely connected to modern concerns about liberation struggles, war, genocide, Black lives, and dissent.

“The pattern of unfulfilled desires has trapped the Antilles and America,” wrote Césaire. Her language suggests the “unfulfilled desires” of people in America are not far away from those in the Caribbean. The logic of surrealism is that accepting and feeding our unconscious desires can help nurture our impulses toward creativity and freedom. Revealing to humankind its unconscious, she wrote, “will aid in liberating people by illuminating the blind myths that have led them to this point.” Under surreal conditions, perhaps, the only way out is through.

The post Recovering Suzanne Césaire’s Legacy appeared first on The Texas Observer.

Leave a Reply