Remember George W. Bush? The 43rd president of the United States is the only living chief executive who appears to actually understand the concept of retirement. But he finds himself back in the headlines this month — in the most George W. Bush of ways.

In a video from a private California event obtained by Axios, the 77-year-old Texan opines onstage about what lies ahead for Israel and Gaza. With a twang straight out of 2003, Bush says that, “I’m kind of a hardliner on all this stuff,” then goes on to dismiss calls for restraint as if they were calls to heed the U.N.’s opinions about WMDs.

“Negotiating with killers is not an option,” he says in an on-stage interview with presidential historian Mark Updegrove. Before long, he’s preemptively dinging public doubts about war. “It’s not going to take long for people [to say], ‘It’s gone on too long. Surely, there’s a way to settle this through negotiations.’”

Lest anyone has forgotten, that weak-kneed approach to evildoers isn’t Bush’s thing. Of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, he adds: “We’ll find out what he made out of.” It’s pretty clear that Bush hopes Netanyahu is made out of whatever substance makes you deaf to namby-pamby calls for diplomacy and caution and the sensitive addressing of terrorists’ root causes.

Agree or disagree with Bush’s analysis of how to respond to Hamas’ gruesome killing spree, the video still makes for jarring déjà vu.

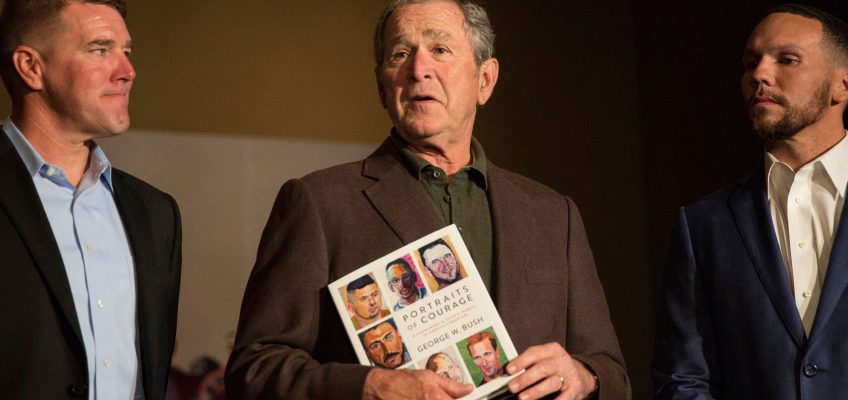

For a decade and a half, we’ve gotten used to a very different W — the hugger of Michelle Obama, the (surprisingly good) painter of wounded warriors and immigrants and the forthright disapprover of insurrectionism, isolationism and nativism. He’s been dissed by MAGA Republicans and embraced by Washington Democrats and rendered largely irrelevant to our political and policy divides.

Now, though, the bloody terrorist assault and the looming war make him seem less like a man out of time than a man of the moment, even without the newsy video.

The president of the United States is making statements that could be lifted from Bush’s post-9/11 heyday: “I’m here to tell you, the terrorists will not win. Freedom will win,” Joe Biden said in Israel on Wednesday. Likewise, the Israeli government, in the immediate aftermath of the bloodbath, began promising to permanently remake the neighborhood — to “change reality for generations,” according to its defense minister. The language seems awfully familiar to Americans who remember our own government’s talk about a new Middle East.

Meanwhile, the realpolitik schemes of the Trump and Biden eras — basically, get Arab autocracies to make peace with Israel in the name of everyone’s bottom line, with minimal yakking about anyone’s human rights — are on hold. The clash of civilizations is back. So are the uncomfortable insinuations about fifth columnists in our midst.

The old divides of the Bush era, papered over during the age of Trump, are also back. “I can’t tell you how many people have said to me, ‘Why can’t we have that guy around?’” Tevi Troy, an aide in Bush’s White House and a longtime veteran of conservative Beltway policy work, told me this week. “Here’s a guy with moral clarity who was always a supporter of Israel.”

On the other end of the freshly revived political chasm: Suffice it to say that after Axios posted the video on social media, the responses included copious examples of phrases like “war criminal,” stills from Abu Ghraib and gifs of things like Iraqi shoe-throwing and the “Mission Accomplished” aircraft carrier speech.

It felt just like old times.

In a way, the dramatic re-emergence of the Bush era represents a good thing — for the American debate, if not for an former president who may have grown unaccustomed to being kicked around. Cocky, callous Decider Dubya has faded into warm, wisecracking Uncle George, but it turns out that memories of naivete and hubris and the pitfalls of launching supposedly transformative wars stuck around. At least some of the advice from American friends of Israel involves urging them to learn from our not-so-great recent example. The battle of Fallujah is showing up a lot in the media, and not because anyone is saying it was a great idea.

Within the American political system, there’s at least some awareness of the perils of an emotional response to terrorism. Whether or not you think this sensitivity should drive policy, it may well be Bush’s singular, and inadvertent, political legacy in Washington.

But it does raise the question of who in the Bush-friendly audience thought it would be a good idea to share the recording of his comments. Updegrove says he didn’t know a video of the interview would be public, though he says he’s glad it’s so. The video isn’t low-quality footage secretly shot by a busboy. It’s unlikely the excerpt would have emerged without the approval of the former president’s camp. Perhaps, after all these years of good vibes, they’d forgotten Bush’s old ability to polarize.

In the context of the past 15 years, in fact, it’s notable that the video emerged at all. If Bush’s presidential legacy was hubris and calamity, his post-presidential legacy is more curious and much more admirable: He’s the one living former president who is not constantly mugging for the cameras.

Ours is the age of the permanent presidency. The deathwatch around 99-year-old Jimmy Carter is largely a function of the 40 years he’s spent as a living humanitarian icon. Barack and Michelle Obama are morphing into a highbrow lifestyle brand, making podcasts and movies. Even a historic defeat couldn’t stop the public Clinton psychodrama. And Donald Trump isn’t even retired from presidential politics, much less public spectacle.

All of them have reason to keep a close eye on their public-approval rating.

Not Bush. “George W. Bush in some ways is more of the traditional former president of yesteryear, much like his father, someone who is content to have his moment on the international stage and then retreat from the spotlight,” says Updegrove, who has written a book about Bush and his father as well as a book about former presidents. “In George W. Bush’s case, I think he has found great joy and fulfillment in being a painter.”

Bush has a foundation to advance good works. But you likely don’t hear much about it, unlike the glitzy gatherings of the Clinton initiative. When hundreds of veterans of Bush’s administration convened in Dallas last summer for a reunion, attendees tell me, they got the sense it might be the last such gathering. That’s mostly a function of age — the former president looked sharp and spent more than an hour working the rope line, but in a decade he’ll be 87. Yet it’s hard to imagine our other POTUSes simply not scheduling a meet-up where they’d be the center of attention.

By one measure, sticking to his easel has worked for Bush. The last time Gallup published a poll of his public standing, it was 59 percent favorable, nearly double his 2008 nadir. Perhaps more tellingly, the last time Gallup polled about him was 2017.

In the years since, Bush’s standing has plummeted among the Republican base he once dominated. But in the Permanent Washington of policy pros and government veterans, he’s regularly cast as a good guy, a link to a better era. It’s a rose-colored image that would amaze many denizens of the capital during the furious years of his presidency.

Both the populist disdain and the centrist strange-new-respect are driven by the same source: Trump.

Particularly since 2020, MAGA die-hards have taken to casting their intra-GOP battle as being specifically against the party’s Bush wing, portraying the dynastic family as devotees of permanent wars, free trade and legalizing the undocumented. In his closing remarks last month at the impeachment trial of far-right Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, Paxton’s lawyer said that “the Bush era in Texas ends today.”

On the other hand, to members of the disinherited Beltway conservative policy establishment who find themselves shut out of newly Trump-oriented outfits like the Heritage Foundation, Bush has become a lodestar of sorts, a man who wouldn’t kowtow to the Kremlin or blow up our international alliances.

For Democrats, he’s also a way to stick it to contemporary Republicans. They’ve emerged as the champions of Bush’s PEPFAR anti-AIDS initiative, casting its GOP critics as heartless. As House Republicans floundered about trying to find a new speaker, Democratic Rep. Brad Sherman, in a not entirely tongue-in-cheek way, suggested Bush’s name. The name is also a convenient general point of comparison for faint praise anti-Trump disses: Bush idiotically tried to occupy the Middle East to export American-style democracy — but at least he liked America and democracy.

Even the fratty Bushian humor, which used to drive lefties nuts, has been embraced at times, as when Trump foes gleefully passed around Bush’s smirking private assessment of his fellow Republican’s 2017 inaugural address: “That was some weird shit.” He was right!

Updegrove says that by keeping mostly mum, Bush guarantees that his infrequent forays into public affairs pack more of a punch. Bush’s first major comment of the Trump years came after Charlottesville, when both presidents Bush jointly put out a statement. “When he does speak out it gets more attention and has more impact because he chooses very carefully the statements he makes and the circumstances under which he makes them,” Updegrove says.

He also notes that, in their on-stage interview, Bush took pains to declare that Hamas didn’t represent all Palestinians, a sentiment consistent with Bush’s own presidency, when he famously visited a mosque after 9/11 and included an imam in the subsequent national memorial service. It’s an instinct that was conspicuously lacking from some of the commentary that followed Hamas’ bloody assault. His declaration actually predated the Biden administration’s recent recalibration of U.S. statements to stress concern for Palestinian civilians.

With war and terror dominating headlines, you can imagine a lot of people on all sides hoping Bush remains part of the conversation. If you’re in Bush’s disproportionately Beltway-based cadre of fans, he’s an avatar of moral seriousness who might sway opinion. If you’re an activist who’s leery of a Gaza invasion, he’s the embodiment of disaster whose thoughts on the Middle East also might sway opinion — in the opposite direction.

I hope he stays retired. Bush’s presidency ended in tears, but his former presidency has been an underappreciated object lesson. It’s an example for fellow chief executives and plenty of other big shots (and, for that matter, medium shots and small shots) in a capital where no one ever seems to stop tending to their brand: You really can just go away.

Maybe Bush’s absence was hastened because he was politically toxic and disowned by his party. Plenty of other pols, though, would have used that as motivation to scrape even harder to get back in our good graces. Yet even people with that earthly motivation might find inspiration in Bush’s example. Sometimes, the best way to win America back is to pipe down and paint.

Leave a Reply