From Lana Del Rey, John Legend and Pulitzer Prize-winning rapper Kendrick Lamar to the members of Radiohead and guitar legends Carlos Santana, Duane Allman and Jerry Garcia, the number of musicians who have cited Miles Davis and his landmark 1959 release, “Kind of Blue,” as prime inspirations grows larger by the year.

“It’s a pioneering album that was a turning point in jazz and it’s also a great bridge to classical and world music,” said pianist and Pulitzer Prize-winning opera composer Anthony Davis.

“I’m not a hardcore jazz fan, but I love ‘Kind of Blue’,” said Melissa Etheridge.

“Discussing Miles makes you feel like a dime-store novelist talking about Shakespeare,” Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood said in a 2001 San Diego Union-Tribune interview. “We’ve taken and stolen from him shamelessly, not just musically, but in terms of his attitude of moving things forward.”

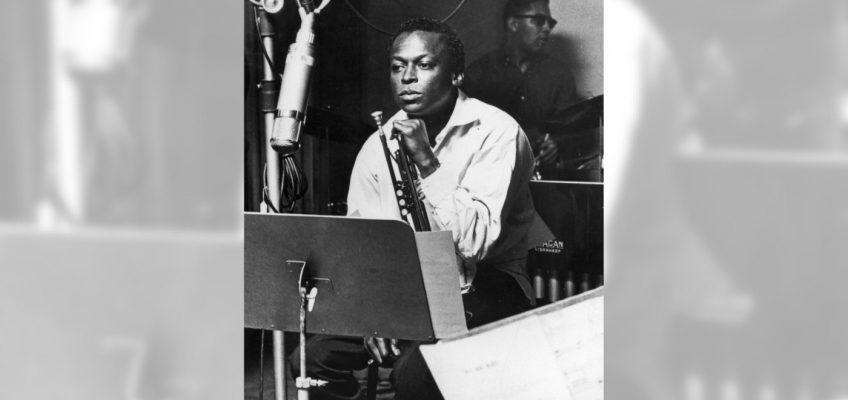

American jazz trumpeter and composer Miles Davis (1926-1991), sits with his instrument during a studio recording session, October 1959. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images/TNS)

Such sentiments come as no surprise to trumpet dynamo and San Diego Symphony jazz curator Gilbert Castellanos, who on Aug. 17 will lead “Miles Davis: Kind of Blue — In Concert” at the Rady Shell at Jacobs Park. Featuring a talent-packed sextet that includes saxophonist Joel Frahm, pianist Donald Vega and drummer Willie Jones III, it will be the sequel to Castellanos’ sold-out 2018 “Kind of Blue” tribute concert at Jacobs Music Center’s Copley Symphony Hall.

“Experiencing ‘Kind of Blue’ is like floating on a cloud in the best dream ever, except that it’s real,” said Castellanos, a veteran local trumpeter and founder of the Young Lions Jazz Conservatory.

“You don’t have to be a jazz fan, or know anything about jazz, to love ‘Kind of Blue.’ Anyone can listen to it and really enjoy it. That is why Miles Davis is heavily responsible for turning a lot of people on to jazz.”

A lot, indeed.

Pink Floyd to Q-Tip

Since its release on Aug. 15, 1959, “Kind of Blue” has become the best-selling jazz album of all time — and the most widely acclaimed — embraced equally by jazz and non-jazz artists alike.

Both Steely Dan co-founder Donald Fagen and A Tribe Called Quest co-founder Q-Tip have called the album “the bible” for music. Pink Floyd keyboardist Richard Wright cited “Kind of Blue” as a prime influence on the structure and tone of parts of Floyd’s classic 1973 album, “Dark Side of the Moon.”

Former Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia was such a big fan that he and mandolinist David Grisman recorded three versions of “Kind of Blue’s” sublime opening number, “So What,” for their joint 1998 album — also titled “So What” — which was released three years after Garcia’s death.

Featuring Davis with a peerless lineup of saxophonists John Coltrane and Julian “Cannonball” Adderly, bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Jimmy Cobb and alternating pianists Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly, “Kind of Blue” is like nothing else in jazz, then or now. The album was instrumental in encouraging Coltrane to explore increasingly daring new sonic vistas for the remainder of his career.

Clocking it at 46 minutes, “Kind of Blue” works equally well as the sole focus for contemplative listening, a plush aural cushion for a lunch or dinner — foreground or background — and just about anything in between.

“The beauty of ‘Kind of Blue’ is that it is this incredible doorway and invitation for anyone to come in and explore this music. But even if you don’t go any further, you will still have a wonderful experience,” said jazz scholar Ashley Kahn, the author of the best-selling 2000 book, “Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece.”

Kahn has also written two books about saxophone giant Coltrane, one of the key players on “Kind of Blue.” The New Jersey-based Kahn is quick to cite the album as a definitive masterpiece.

“It features an unbelievable, once-in-a-lifetime aggregation of such immortal players and such distinctive songs.” he said. “Every time they touched their instruments to solo on ‘Kind of Blue,’ what resulted was timeless. The album transcended its time and its genre.”

Recorded in just nine hours on March 2 and April 22, 1959, “Kind of Blue” boasts five indelible songs that, to this day, are performed by jazz ensembles around the world — “So What,” “Freddie Freeloader,” “Blue in Green,” “All Blues” and “Flamenco Sketches.” It is an album on which nuance, beauty and impeccably calibrated group improvisations trump the high-octane virtuosity and velocity that came to the fore with the bebop revolution that dominated jazz from the early 1940s to at least the mid-1950s.

Gorgeous, unhurried melodies abound on “Kind of Blue,” which does not have a single up-tempo song. Conventional chord sequences and harmonies are put aside in favor of a modal approach that — much like the ragas that are foundational in the classical music of India — focus on scales, or modes, specifically the eight notes that go from one octave to the next.

Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Anthony Davis teaches a course at UC San Diego that focuses on the five most pivotal jazz albums released in 1959, including Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue.” (Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

‘Incredibly lyrical’

Davis was introduced to the concept by noted composer and musical theorist George Russell, who spent much of the 1950s quietly exploring the possibilities of a modal jazz approach. It was a game-changing innovation that other artists had delved into. But they had done so only briefly and tentatively, let alone on an epic, game-changing album like “Kind of Blue.”

“When you go this way, you can go on forever,” Davis told music critic Nat Hentoff in 1958. “You don’t have to worry about (chord) changes, and you can do more with time (signatures). It becomes a challenge to see how melodically inventive you are. … I think a movement in jazz is beginning, away from the conventional string of chords and a return to emphasis on melodic rather than harmonic variations. There will be fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them.”

Those infinite possibilities provided a launching pad for “Kind of Blue.” But rather than meander here, there and everywhere, the album is a marvel of seemingly opposite musical values: precision and fluidity; focus and surprise; risk and a shared sense of purpose.

Accordingly, much of “Kind of Blue” was created spontaneously as it was being recorded, with Davis providing only bare sketches and ideas of what he wanted his musicians to do. Almost all the selections on the “Kind of Blue” are first-take recordings, the better to achieve Davis’ goal of having his band members focus on the deeply felt emotions of the songs rather than over-thinking them.

“It was primarily a one-take which reflects ‘the first thought is the best thought’ aesthetic that comes out of jazz but is really a classic Miles-ian thing,” said author Kahn.

“There’s a perfect storm quality to the album: Miles in his prime with a great, once-in-a-lifetime band; first-rate audio engineers; a terrific record label, Columbia, that treated all musicians in all genres equally well and launched ‘Lind of Blue’ into the world. Within two to three years, it was already the best-selling album in jazz, and — a few years after that — was influencing everyone from (pioneering minimalist composer La Monte Young to the Allman Brothers and, of course, many, many jazz artists.”

Had author Aldous Huxley’s 1954 book not been titled “The Doors of Perception,” it might have made a good subtitle for what remains to this day Davis’ most widely embraced and acclaimed recording.

“The modal music on ‘Kind of Blue’ opened up a whole world of engagement,” said Pulitzer Prize-winning opera composer Anthony Davis. An accomplished jazz pianist, he teaches a course at UC San Diego that focuses on “Kind of Blue” and four other standout jazz albums released in 1959. He is not related to Miles Davis, who died in 1991 at the age of 65.

” ‘Kind of Blue’ not only looks beyond diatonic harmonies,” Anthony Davis said, “but also to world music and to classical music, especially the compositions of Debussy and Ravel, who were a major influence on the album. Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand provided some of the inspiration for ‘All Blues’ on ‘Kind of Blue.’

“Plus, the album is incredibly lyrical. Miles’ playing is just so pristine and the solos are so memorable. So is the contrast between the playing of Coltrane and Cannonball, and Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly, whose solos I transcribed a lot when I was a student at Yale. The cyclical 10-bar structure on ‘Blue in Green’ is very innovative. And the album is incredibly lyrical and speaks in a very clear way.”

That clarity and lyricism also had a profound influence on 1970’s “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” one of the most beloved songs by The Allman Brothers Band. Its graceful, spiraling melodies, uncluttered rhythms and deeply felt solos owe a major debt to “Kind of Blue,” as guitarist Duane Allman acknowledged at the time to Rolling Stone writer Robert Palmer.

“You know, that kind of playing comes from Miles and Coltrane, and particularly ‘Kind Of Blue’,” Allman said. “I’ve listened to that album so many times that for the past couple of years, I haven’t hardly listened to anything else.”

For trumpeter Castellanos, hearing “Kind of Blue” for the first time as an eighth-grade student in Fresno was life-changing.

“It was so inspiring and it really knocked my socks off!” he recalled. “I remember going home from school that day and trying to figure out how Miles got that muted sound, I had the same trumpet mute, but couldn’t figure out what he was doing make it sound so warm and beautiful.

“The trumpeters I’d been listening to then, like Freddie Hubbard and Maynard Ferguson, were all about playing fast and loud. And then, with ‘Kind of Blue,’ I heard the exact opposite of that. Miles’ playing had the quality of a human voice whispering to you. That changed my whole approach to the trumpet, and that was the hardest thing to learn. Even at the age I am now, in my early 50s, it’s difficult to make the trumpet sound so warm and pretty.”

Given how familiar many Davis fans are with literally every note on “Kind of Blue,” including all the solos, performing it here live on stage raises intriguing questions.

Will Castellanos and his band mates reverently play the music, note for note, at their Aug. 17 Shell concert? (The first half will feature other selections from Davis’ expansive repertoire.)

Will they take liberties to extend the album in real time, using the recorded version as a launching pad? Or will they combine both approaches in a way that is respectful of “Kind of Blue,” but not beholden to it? Or is it a sacrilege to change the music in any way?

“It is absolutely not a sacrilege if we don’t play it note for note,” Castellanos replied.

“Of course, we will play the melodies absolutely like they are on the album, with a frontline of two saxophones and trumpet. But what I’m really looking forward to is how these phenomenal musicians approach ‘Kind of Blue’ from their own perspectives as they improvise over the beautiful melodies.

“I have four copies of the album including a rare, original first-pressing in mono. For me, ‘Kind of Blue’ could be the soundtrack to anyone’s life.”

Singing Miles Davis’ praises

Many musicians have happily cited Miles Davis as a major inspiration in interviews over the years with the San Diego Union-Tribune. Here are some of their comments.

David Bowie: “Miles genuinely did more than anyone to create what avenues you can dare to walk in music. He made extraordinary breakthroughs.”

Lenny Kravitz: “People talk about what’s new in music, and about taking it really far out. And I’m like: ‘Man, I haven’t heard anybody take it further out than Miles, and that was years ago.’ “

Keyboard legend Chick Corea: “The best lesson Miles gave all of us was his total artistic integrity. Anything he wanted to do, musically, and give to an audience, he would not water it down one inch. He wouldn’t let pressures from the world around him change anything he was doing. And he changed the world.”

Pearl Jam drummer Matt Cameron: “In every kind of creative musical endeavor, you want to be fearless. And that’s what Miles instilled in me — the fact that you can be as fearless as you’re able to be. I’ve been directly inspired and influenced by him.”

Bass great Dave Holland: “Having the chance to play with Miles was like getting a call from Duke Ellington or Louis Armstrong. He was always his own person, and not afraid to take a stand when he wanted to. He would always take a new path and see where it would take him. Miles was always developing and making it new, every night.”

Singer-songwriter David Gray: “Miles was a brilliant catalyst who grew music around him, and he was so sophisticated and ahead of his time. He created this space where strange but beautiful flowers bloomed. And as a band leader, he’s one of the greats of the 20th century. He expanded the world of music countless times, and now we take it all for granted.”

Leave a Reply