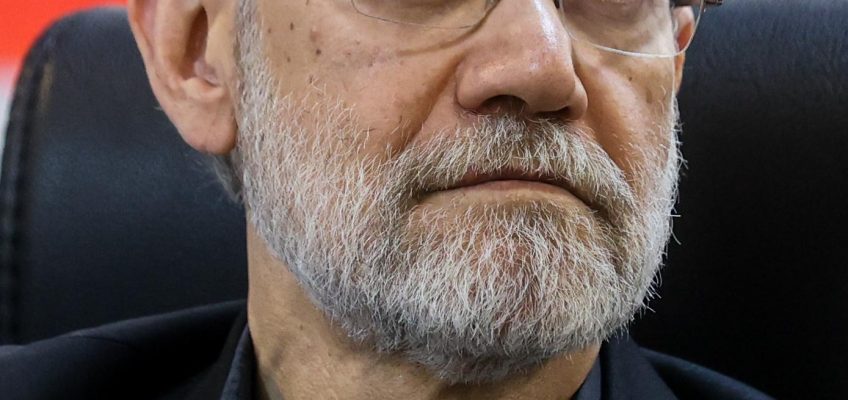

In early January, as Iran faced nationwide protests and the threat of strikes by the United States, the nation’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, turned to a trusted and loyal lieutenant to steer the country: Ali Larijani, the country’s top national security official.

Since then, Larijani, 67, a veteran politician, a former commander in the Revolutionary Guard and current head of the Supreme National Security Council, has effectively been running the country. His rise has sidelined President Masoud Pezeshkian, a heart surgeon turned politician, who has faced a challenging year in office and continues to say publicly that “I’m a doctor, not a politician” and that no one should expect him to solve the multitude of problems in Iran.

This account of Larijani’s ascent and the decisions and deliberations of Iran’s leadership as the Trump administration threatens war is based on interviews with six senior Iranian officials, one of them affiliated with Khamenei’s office; three members of the Revolutionary Guard; two former Iranian diplomats; and reports from the Iranian news media. The officials and members of the Guard spoke on the condition of anonymity to candidly discuss internal government matters.

Larijani’s portfolio of responsibilities has grown steadily over the past few months. He was in charge of crushing, with lethal force, the recent protests demanding the end of Islamic rule. Currently, he is keeping a lid on dissent, liaising with powerful allies like Russia and regional actors like Qatar and Oman and overseeing nuclear negotiations with Washington. He is also devising plans for managing Iran during a potential war with the United States as Washington amasses forces in the region.

“We are ready in our country,” Larijani said in an interview with Al Jazeera when he visited the Qatari capital, Doha, this month. “We are definitely more powerful than before. We have prepared in the past seven, eight months. We found our weaknesses and fixed them. We are not looking for war, and we won’t start the war. But if they force it on us, we will respond.”

(BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM.)

Khamenei has instructed Larijani and a handful of other close political and military associates to ensure the Islamic Republic survives not only American and Israeli bombs, but also any assassination attempts on its top leadership, including on Khamenei, according to the six senior officials and the Guard members.

Nasser Imani, a conservative analyst close to the government, said in a telephone interview from Tehran that Khamenei has a long and close relationship with Larijani, and the supreme leader turned to him in this time of acute military and security crisis.

“The supreme leader fully trusts Larijani. He believes Larijani is the man for this sensitive juncture because of his political track record, sharp mind and knowledge,” Imani said. “He relies on him for reports on the situation and pragmatic advice. Larijani’s role will be very pronounced during war.”

Larijani comes from an elite political and religious family, and for 12 years he was the speaker of the parliament. In 2021, he was put in charge of negotiating a 25-year comprehensive strategic deal with China worth billions.

According to the six senior officials and the Guard members, Khamenei has issued a series of directives. He has named four layers of succession for each of the military command and government roles that he personally appoints. He has also told everyone in leadership roles to name up to four replacements and has delegated responsibilities to a tight circle of confidants to make decisions in case communications with him are disrupted or he is killed.

(END OPTIONAL TRIM.)

While in hiding last June during the 12 days of war with Israel, Khamenei named three candidates who could succeed him. They have never been publicly identified. But Larijani is almost certainly not among them because he is not a senior Shiite cleric — a fundamental qualification for any successor.

Larijani is, however, ensconced in Khamenei’s trusted circle. That includes his top military adviser and former commander in chief of the Guard, Maj. Gen. Yahya Rahim Safavi. It also includes Brig. Gen. Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, a former Guard commander and current speaker of parliament whom Khamenei has designated as his de facto deputy to command the armed forces during the war; and his chief of staff, cleric Ali Asghar Hejazi.

(BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM.)

Some of this planning is the result of lessons drawn from Israel’s surprise attack in June, which wiped out Iran’s senior military command chain within the first hours of the war. After the ceasefire, Khamenei appointed Larijani as the secretary of the National Security Council and created a new National Defense Council, headed by Adm. Ali Shamkhani, to manage military affairs during wartime.

“Khamenei is dealing with the reality in front of him,” said Vali Nasr, an expert on Iran and its Shiite theocracy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

“He is expecting to be a martyr and thinking this is my system and legacy, and I will stand until the end,” Nasr said. “He is distributing power and preparing the state for the next big thing, both succession and war, aware that succession may come as a consequence of war.”

(END OPTIONAL TRIM.)

Iran is operating on the basis that U.S. military strikes are inevitable and imminent, even as both sides continue to engage diplomatically and negotiate on a nuclear deal, the six officials and three Guard members said. They said Iran had placed all of its armed forces on the highest state of alert and was preparing to resist fiercely.

The country is positioning ballistic missile launchers along its western border with Iraq — close enough to strike Israel — and along its southern shores on the Persian Gulf, within range of U.S. military bases and other targets in the region, the three Guard members and four senior officials said.

In the past few weeks, Iran has closed its airspace periodically to test missiles. It also held a military exercise in the Persian Gulf, briefly closing the Strait of Hormuz, a major maritime choke point for global energy supplies.

All the while, Khamenei has maintained a defiant front. “The most powerful military in the world might receive such a slap that it won’t be able to get on its feet,” he said in a speech recently. He also threatened to sink the U.S. warships that have gathered in nearby waters.

In the event of war, the special forces units of the police, intelligence agents and battalions of the plainclothes Basij militia, a subsidiary of the Guard, are to be deployed to the streets of major cities, the three Guard members and two senior officials said. The militias would then set up checkpoints to forestall domestic unrest and look for operatives linked to foreign spy agencies.

The Iranian leadership is preparing not only for military and security mobilizations, but also for its own political survival. These deliberations, described by six officials familiar with the planning, touch on a range of matters, including who would manage the country if Khamenei and top officials were killed.

The leaders have considered who could be “the Delcy of Iran” — a reference to Delcy Rodríguez, the Venezuelan vice president who made a deal with the Trump administration to run Venezuela after the capture of its president, Nicolás Maduro.

Larijani sits at the top of the list, the three officials said. He is followed by Ghalibaf, the parliament speaker. Somewhat surprisingly, a former president, Hassan Rouhani, who has been largely cast out of Khamenei’s circle, also made the list.

Each of these men has records that would limit their acceptance by an angry populace — whether it is accusations of financial corruption or of being complicit in Iran’s violations of human rights, including the recent killing of at least 7,000 unarmed protesters over three days.

Ali Vaez, the Iran director of the International Crisis Group, said the leadership had made contingency plans, but the repercussions of war with the United States remain unpredictable. The supreme leader, he said, “is less visible, more vulnerable, but he is still the superglue keeping the system together and everyone understands that if he is not there any more it would be hard to keep the system together.”

(STORY CAN END HERE. OPTIONAL MATERIAL FOLLOWS.)

In the past month, Larijani’s visibility has soared as Pezeshkian’s has diminished. He flew to Moscow to consult with Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, and has met with Middle Eastern leaders, in between meetings with U.S. and Iranian nuclear negotiators. He has sat for hourslong television interviews with Iranian and foreign news outlets, more often than the president, and regularly posts content on social media like photographs of himself taking selfies with Iranians, visiting a religious shrine and waving from the door of an airplane.

For his part, Pezeshkian appears resigned to deferring authority to Larijani. The president told a Cabinet meeting that he had suggested to Larijani that he should lift internet restrictions because they were harming e-commerce, Iranian media reported. It was a jarring admission that to get things done, even the president had to appeal to Larijani.

In January, amid the crackdown on protests, the U.S. Middle East envoy, Steve Witkoff, tried to contact Iran’s foreign minister, Abbas Araghchi, said two senior Iranian officials and a former diplomat. President Donald Trump had said he would strike Iran if it executed any protesters, and Witkoff was seeking out Araghchi to ask if executions were planned or had been called off, they said.

Anxious to forestall any misunderstandings, the two senior officials said, Araghchi called the Iranian president asking if he could establish contact with Witkoff. Pezeshkian replied that he did not know and to call Larijani for authorization.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Leave a Reply