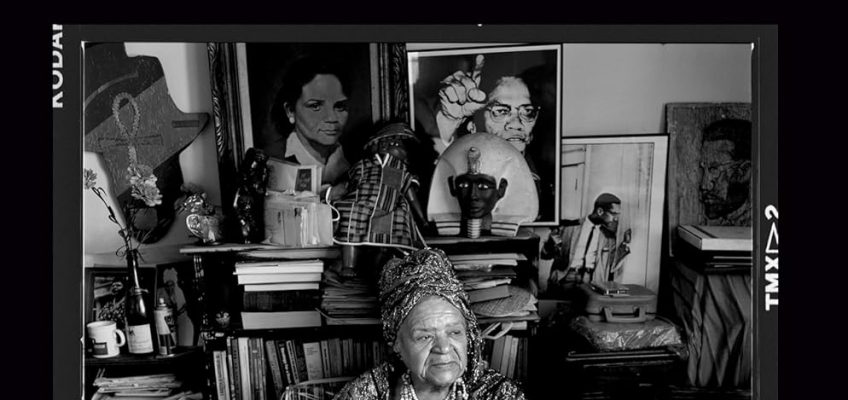

The image that graces the cover of historian Ashley Farmer’s new biography of Pan-African activist Audley “Queen Mother” Moore is no less regal than the iconic photograph of Black Panthers founder Huey Newton in a rattan throne chair that many of us are more familiar with.

Moore sits in an old striped armchair, wearing an African-print caftan and headdress, neck draped with beads, wrist adorned with bangles. Behind her, portraits of Malcolm X and Winnie Mandela hang on the wall. But, as Farmer notes in her introduction to Queen Mother: Black Nationalism, Reparations, and the Untold Story of Audley Moore (out from Pantheon on November 4), “What we know of Audley Moore, one of the most important activists and theorists of the twentieth century, remains largely confined to a few photos such as this one—a seven-decade history of struggle distilled down to a few still shots. Until now.”

In her book, Farmer, a historian of Black women’s radical politics and an associate professor of History and African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, chronicles Moore’s life and activism. Moore, a civil rights leader and Black nationalist, adopted the name Queen Mother in the 1960s as a symbol of both her matriarchal presence in Black organizing spaces as well as the connection to Africa that was key to her politics. From her roots in southern Louisiana at the dawn of the 20th century to her years pounding the pavement in Harlem as an organizer for the Communist Party to her reignition of the modern reparations movement well into her later years, Moore’s story offers a potent lesson for today’s organizers on the power of persistence, longevity, and showing up.

Born in 1897 in New Iberia, Louisiana, to a mother from a free Black community and a father born into slavery, Moore bore witness to the dying breaths of Reconstruction in the South. Though she enjoyed membership in the Creole elite upon moving with her father to New Orleans, she found herself cut off from that wealth and access upon his death while she was still in high school. Newly a member of the working class, taking up domestic labor to provide for herself and her two younger sisters, the arrival of Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, one of the foremost proponents of the Back-to-Africa movement, laid the cornerstone of Moore’s political philosophy for the rest of her life.

“It was Garvey who brought consciousness to me,” she recalled in an oral-history interview quoted in the book. “You can experience a thing without being conscious of yourself. … [You can] see the brutality of the police all against us and so on, and yet a consciousness is not aroused.”

From then on, Moore would see herself as a vital part of a global Black community and as working in service of Black liberation.

Moore and her then-husband were ready to follow Garvey to Africa, making his vision of an Africa for Africans a reality—the pair had sold their grocery store and packed their trunk—before extended family interceded. Still, the two were ready to leave New Orleans, and they decamped to Harlem in the mid-1920s. Harlem proved a fertile ground for Moore to come into her own as an organizer. After attending a rally led by the local Communist Party, she was invigorated by a speech wherein party leader James Ford expounded on imperialism in Africa and the struggle of the international working class. By 1936, she was a card-carrying party member, selling copies of The Daily Worker and helping to articulate a vision of a fight against capitalism and white supremacist imperialism both at home and abroad.

During Moore’s time in the party, she rose through the ranks, organizing around bread-and-butter issues like tenants’ rights and grocery affordability, eventually leading the Upper Harlem Branch’s Women’s Commission. She’d go on to run for the New York State Assembly on the Communist Party ticket and help elect a Black Communist to represent Harlem on the New York City Council. Farmer writes: “Moore’s ideological compass was always pointed at Black Nationalism. But she had a malleable approach to organizing that led her to join groups, protests, and causes that were pro-Black even if they were not explicitly nationalist.”

Though J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI began targeted surveillance of Moore in 1941, it wasn’t this threat that weakened her ties to the Communist Party but rather the party’s own lack of a commitment to her Black nationalist vision that led her to renounce membership in 1950.

Even after her time in the Communist Party, Moore retained the understanding that civil rights alone wouldn’t give her the results she wanted; it would take capital to ensure that Black people could be truly free. Symbolic and material reparations were not a novel idea, but back home in Louisiana, where Moore returned in 1956 with her sisters after a successful campaign to reclaim the house that their half-brother had kicked them out of decades earlier, Moore launched the modern reparations movement. She tasked the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, her organizing home which until then had largely been advocating for Black men on death row, with researching historical claims to reparations for Black Americans.

Ever the tactician, Moore was capacious in her vision, appealing to more-moderate constituencies with plans for hiring quotas and job-training programs as well as to armed Black separatists like those of the Republic of New Afrika, who wanted to found a sovereign Black nation in Mississippi.

The fight for reparations carried Moore through the second half of the 20th century. She continued advocating, benefitted by a longevity in the movement that most Black nationalist leaders were denied, their lives too often cut short. Until her death, in 1997, if Black people were gathering to discuss political objectives, whether in the United States or the United Kingdom or Africa, Queen Mother Moore was there to remind them that, even as the political landscape changed—Africa decolonized, voting rights achieved—reparations were critical to any vision of a liberated Black political future.

Farmer mirrors Moore’s tenacity in her insistence on chronicling her subject’s life at all, in the face of an academic establishment claiming that, without substantial archives, a definitive biography was a fruitless project. Our understanding of the history of Black activism, with its points both high and low, will be fuller for Farmer’s portrait of Moore, who offers those of us who struggle toward justice a model for playing the long game.

The post The ‘Queen Mother’ of the Reparations Movement Gets Her Due appeared first on The Texas Observer.

Leave a Reply