After the partial collapse of a NYCHA building in the Bronx, tenants are split on how to best address deteriorating conditions in the city’s public housing stock. Stay in underfunded Section 9, or convert to Section 8—and potentially, to private management?

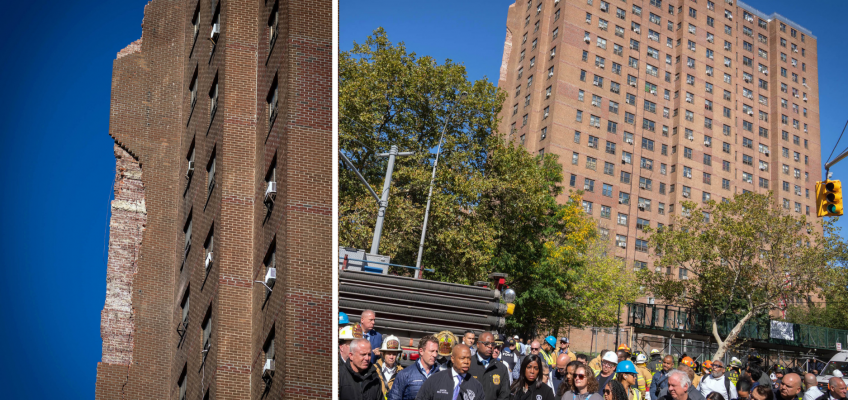

Scenes from Oct. 1 at NYCHA’s Mitchel Houses, where part of a building collapsed. (Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

First, an explosion. Then, a partial building collapse. After a boiler in the central building of the Mitchel Houses’ NYCHA campus in the Bronx was turned on Oct. 1, an explosion sent shockwaves up the building’s chimney, which collapsed 20 stories to the walking path below.

The disaster, which fortunately resulted in no injuries, was a grim reminder of the precarious state of the city’s public housing stock, which has a deep backlog of repairs, and forces NYCHA’s nearly 400,000 residents to live in sometimes unsafe conditions.

“I could feel my anxiety going off, and I think for a lot of the tenants, when I talk to them, it’s the same thing, like it felt like a war zone had come into our homes,” said Ramona Ferreyra, who lives in a neighboring building at the Mitchel Houses.

While NYCHA and the city investigate what went wrong, tenants and housing experts worry that what happened at Mitchel could happen again.

“Every delay in repairing public housing has real consequences for New Yorkers,” said Jessica Katz, one of the leaders of the NYCHA Regeneration Initiative and the city’s former chief housing officer under Mayor Eric Adams. “We can’t continue to defer maintenance at the expense of residents’ health and safety.”

A City Limits analysis of NYCHA physical needs assessments found that many developments have similar levels of wear as the Mitchel houses did before the collapse—or worse.

“NYCHA continues to work in close coordination with our oversight and city agency partners in the response to the incident at Mitchel Houses. Although this work is ongoing, it appears thus far that this was an isolated incident and not a systemic issue that would impact other developments,” said Michael Horgan, a spokesperson for NYCHA in a statement.

But residents of NYCHA, like Manhattan tenant Mike Noble, said the incident is “a wake up call.”

“This is the kind of hidden stuff that can happen at any time,” he said.

Precarious conditions

The big number: $78 billion dollars. That 2023 estimate of the 20-year capital repair need at NYCHA looms over conversations about the state of the city’s beleaguered public housing stock.

“Sometimes people’s eyes just kind of glaze over when they hear that because I think it isn’t tangible anymore, right?” said Danny Rivera, a housing policy analyst who grew up in NYCHA. “It just becomes this big number that doesn’t feel solvable.”

Noble, a resident at the Elliott Houses, said those numbers boil down to a simple truth: conditions in many NYCHA buildings are simply bad.

The collapse, he said, shows the extent of underinvestment. “I was shocked but not surprised. Stuff like that happens, and these buildings are just so old,” he said.

Living with the fear of collapse isn’t the only thing hovering over residents’ heads. There are daily issues that can cause health hazards, like mold, leaks, and broken elevators.

People waiting for one functioning elevator at a building in the Mitchel Houses in 2023. (Adi Talwar/City Limits)

The Mitchel Houses has $725 million in repair needs, mostly allocated for individual apartment repairs—an estimated $400,000 per unit—and for fixing heating, windows and building exteriors.

But 204 of the other 264 NYCHA developments have more significant repair needs per unit than Mitchel.

In addition to NYCHA’s own physical needs assessment conducted every five years, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) inspectors score the conditions of buildings annually and flag significant health and safety issues.

A City Limits’ data analysis shows that over half of NYCHA developments failed their physical inspection in 2024, with dozens reporting serious health and safety issues in recent evaluations by HUD’s Real Estate Assessment Center (REAC).

In 2022 and 2023, the situation was even worse: 85 percent of NYCHA developments failed their evaluations, and “life threatening” health and safety issues were found in all but one development HUD inspected. Those violations included electrical, ventilation and heating issues, and security problems like unlocked windows and doors.

HUD changed the inspection procedure in 2024, and health and safety subscores were no longer available. A spokesperson for NYCHA said efforts to improve daily maintenance helped increase their average inspection score, which rose from 35 in 2022-2023 to 63 last year.

Last week, HUD laid off the entire team responsible for inspecting federally subsidized housing, according to a Bloomberg report.

Where to go from here

In light of the collapse, “people are evaluating the true status of their buildings,” said Noble.

Since 2023, NYCHA residents at select developments are voting on the future of their housing: whether they want to keep the status quo, or change funding structures to unlock repairs.

One proposed solution is to convert traditional public housing under the federal Section 9 program to Section 8 vouchers tied to specific units on NYCHA campuses. Those so-called project-based subsidies have more money attached from the federal government, unlocking dollars NYCHA can use on its deep repair backlog.

Residents can vote to stay in Section 9, or convert to Section 8—either by turning management over to a private company through a program called Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT), or to continue with NYCHA as their manager by entering the Public Housing Preservation Trust, a public entity New York State set up in 2022.

Noble and Ferreyra saw the challenges at their developments, and chose two different paths.

At the Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses on the west side of Manhattan, Noble is supporting a plan to redevelop the entire complex by demolishing and then replacing the NYCHA apartments. The plan, which officials are moving ahead with this fall, will also add more affordable and market-rate housing on the campus.

He says the existing properties are just too far gone. “The amount of decay in these buildings is just way, way too much. And not only that, if you were to rehab this building, put it right back to the way it looked when it was built, it would still be inadequate,” said Noble.

In the Bronx, Ferreyra founded a group called Save Section 9, which has been pushing voters at NYCHA campuses to stick with traditional public housing. Last August, the Coney Island Houses became the first development to vote for staying with Section 9.

So far, four developments have voted to enter the Public Housing Trust, two have voted to stay in Section 9, and one has chosen PACT.

Fulton Elliot-Chelsea is the first campus to undergo comprehensive redevelopment as part of its PACT plan, but many developments that have gone through the program have had less dramatic change, such as rehabilitation of existing units that did not require tenants to move.

Ferreyra, who lives in the Mitchel Houses, says her determination to stay with Section 9 is still strong even after her neighboring building partially collapsed.

“Our neighbors really matter to us,” said Ferreyra, who said public housing has a unique culture they cannot afford to lose. “Being a public housing resident, even if it comes with these challenges that we all face, is better than losing our Section 9 designation and becoming a Section 8 tenant.”

The entrance to NYCHA’s Mitchel Houses building for seniors in The Bronx. (Adi Talwar/City Limits)

The federal government, which supports two-thirds of NYCHA’s operations, has been disinvesting in public housing for decades, leaving local governments to fill gaps.

“I think the city and the state are going to have to develop more responsible budgeting priorities when it comes to public housing,” said Ferreyra.

So far, that local support has not materialized in a way that can make a dent in the deep capital needs hole.

That can be a tough sell to some developments. “We tell them after you vote to stay Section 9, you’re going to have to start a second fight to get the funding necessary to do these repairs,” said Ferreyra.

It might not be the right fight for every development. “We look at the physical needs assessment and we decide if it’s safe for the tenants to take on that fight,” she added.

Some housing experts suggest there is a tipping point where the complexity of repairs means demolition and replacement might be a more viable option. For developments with more than $500,000 in capital needs per apartment, the authority may be able to build new for cheaper.

That’s the blueprint for the Elliott Houses, where Noble says his development has been left behind. “If everybody around us is living so well and has the safety and the amenities to go along with it, right, why don’t we? Why aren’t we entitled to that as well?” he said.

Other experts and tenants point out that each building has different physical needs and different political constraints—and the right repair solution will be an alchemy of what is financially and politically viable.

What can public housing residents do? Advocate for themselves, said Rivera.

“Every tenant in public housing deserves good quality housing,” he said. “I can’t tell them what the right choice is like. No one can. I think they just need to have the resources around them to make informed choices.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Patrick@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.

The post Most NYCHA Developments Have Greater Repair Needs Than Partially-Collapsed Mitchel Houses, Inspections Show appeared first on City Limits.

Leave a Reply