By TRAVIS LOLLER

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) — Bobby Cain, who helped integrate one of the first high schools in the South in 1956 as one of the so-called Clinton 12, died Monday in Nashville at the age of 85, according to his nephew J. Kelvin Cain.

Related Articles

Maine wardens rescue moose trapped for hours in abandoned well

How a SIM farm like the one found near the UN threatens telecom networks

Iran’s supreme leader rejects direct talks with US over his country’s nuclear program

‘Nightmare bacteria’ cases are increasing in the US

Missouri woman gets more than 4 years in prison for trying to sell off Elvis Presley’s Graceland

Bobby Cain was a senior when he entered the formerly all-white Clinton High School in Tennessee on a court order. He had previously attended a Black high school about 20 miles away in Knoxville and was not happy about leaving his friends to spend his senior year at a new school in a hostile environment.

“He had no interest in doing it because, you know, he’d gotten to rise up through the ranks at Austin High School as the senior and was finally big fish in the pond. And to have to go to this all-white high school — it was tough,” said Adam Velk, executive director of the Green McAdoo Cultural Center, which promotes the legacy of the Clinton 12. Velk added that the 16-year-old had to do it “with the entire world watching him.”

This was a couple of years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v Board of Education that separating public school children on the basis of race was unconstitutional and a year before Little Rock Central High School was desegregated by force. Unlike the Little Rock Nine, the Clinton 12 students were not hand-picked and trained for the job of desegregation. They just happed to live within the Anderson County school district at the time, Velk said.

Although the court-ordered desegregation in Clinton was accepted by state and local authorities, many in the local white community were against it. They were soon joined by Ku Klux Klan members and other segregationists from outside the community in a series of protests that led to the National Guard being called in to restore order.

Cain managed to stick out the year, becoming the first Black student in Tennessee to graduate from an integrated state-run school. What should have been a triumphant moment was marred by violence. After receiving his diploma, Cain was jumped and beaten up by a group of white students. In the end, only one other member of the Clinton 12 made it to graduation. Gail Ann Epps graduated the following year, according to the Tennessee State Museum.

Cain had a lot of anger around his experience at the school and didn’t talk about it for many years.

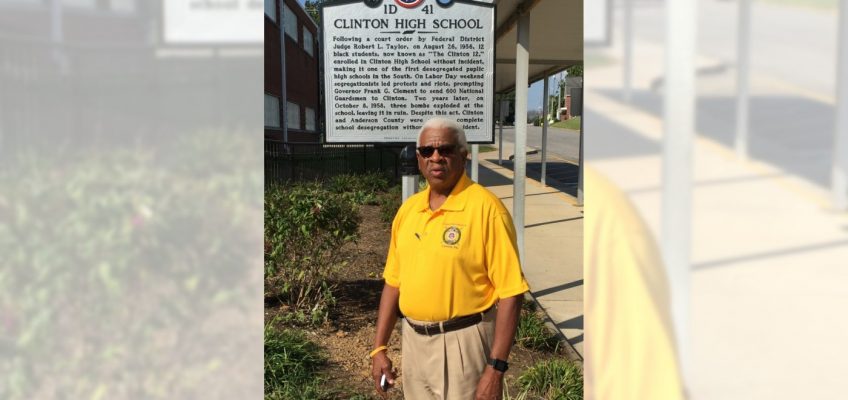

Bobby Cain poses poses for a photo in the Civil Rights Room of the Nashville, Tenn., Public Library in October 2017. (Robin Conover/The Tennessee Magazine via AP)

“He didn’t want to remember it,” his nephew said.

He received a scholarship to attend Tennessee State University in Nashville, where he met his wife. After graduation, he worked for the Tennessee Department of Human Services and was a member of the U.S. Army Reserve. He never joined in the sit-in protests of the era, quipping to The Tennessee Magazine in a 2017 interview that it was because “you had to agree to be nonviolent.”

Cain told the magazine that he had no white friends at Clinton High School.

“You have to realize that if any white students had gone out of their way to be nice to us, they would have been jumped on,” he said.

He also had to stop playing sports because “the coaches at Clinton told me that none of the other high schools would play against us if I was on the field at the game.”

Velk calls Cain a reluctant hero.

“This is a normal, everyday human being who found themselves in extraordinary circumstances and acted above those circumstances,” Velk said. “This is a person who dealt with this tremendous difficulty and rose to the occasion.”

Cain is survived by a daughter, Yvette Cain-Frank, and grandson Tobias Cain-Frank.

Leave a Reply