And so the purge continues. Some of us used to think, or hope, that President Donald Trump’s campaign of “retribution” would prove brutal but short, leaving American statecraft bruised but functional. The news flow suggests a different direction. As Senator Mark Warner puts it, “when expertise is cast aside and intelligence is distorted or silenced, our adversaries gain the upper hand and America is left less safe.”

Warner, a Democrat who is vice chair of the senate’s intelligence committee, was referring to the firing of Lieutenant General Jeffrey Kruse as director of the Defense Intelligence Agency. The DIA is the Pentagon spy outfit that concluded in an initial assessment after the American bombing of Iran in June that the strikes had probably set back Tehran’s nuclear efforts only by months. That contradicted Trump’s narrative, in which he had “obliterated” Iran’s program. Goodbye Kruse.

His fate is just one instance in a pattern that began as soon as Trump returned to the White House. For months, his administration has been ridding its national-security apparatus, diplomatic corps and other executive-branch cadres of anybody it deems potentially “disloyal,” often on the advice of MAGA conspiracy theorists who aren’t even in government, have no expertise, and think grounds for termination should include such things as, say, service in the administration of Joe Biden.

The witch hunt doesn’t have to entail termination. In another act of vicarious vengeance, Tulsi Gabbard, the director of national intelligence, just revoked the security clearances for 37 people currently or formerly in government, in many cases ending their careers. Their sin was involvement in an assessment which the intelligence community made in 2017 (and which the Senate intelligence committee later validated) that Russia had meddled in the American election of 2016. Trump calls it the “Russia hoax.”

In that way, Gabbard yet again sacrificed scarce and even unique expertise to please the president. For example, one of the 37, Vinh Nguyen at the National Security Agency, was a specialist in data science and cyberthreats, and specifically in the artificial-intelligence contest with China. The folks in Zhongnanhai must be popping baijiu corks.

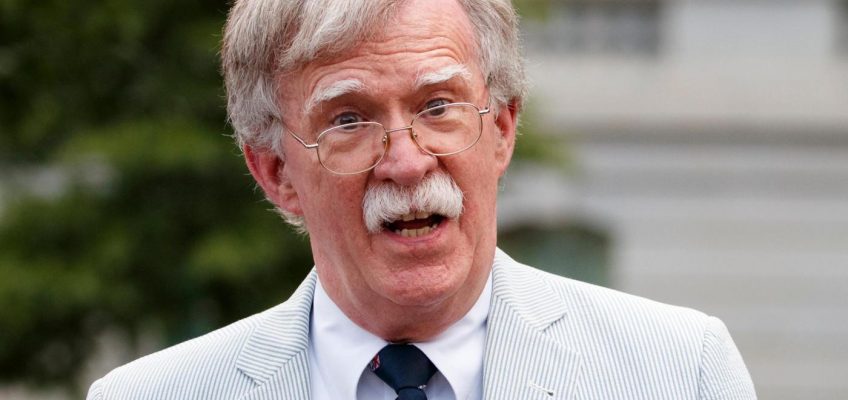

Kruse, Nguyen and their ilk are not household names. John Bolton is. He was one of the National Security Advisors in Trump’s first term but subsequently became a scathing critic (who warned that Trump’s encore would be a “retribution presidency”). On day one of his second term, Trump took away Bolton’s security detail (even though Bolton is personally under threat from Iran). On Friday the FBI rifled through Bolton’s house, ostensibly in search of classified documents he may or may not have mishandled. Like all the firings and revocations, the raid sends the chilling message that it doesn’t matter what you know, only whether you’re with Trump.

But if you are with him, you’re not down and out but up or in. For ambassador to India — the world’s most populous country and a vital, if complicated, frenemy of the United States — Trump just nominated Sergio Gor, a political operative whose only qualification seems to be his work as a fundraiser and aide to the president. Charles Kushner is ambassador to America’s oldest ally, France, and in over his head — the father of Trump’s son-in-law, Kushner is a real-estate developer who once did a stint in prison for white-collar crimes (although Trump later pardoned him). On it goes.

From the middle rungs of government to the top floors, fealty is supplanting expertise. Gabbard, like her counterparts at the CIA and FBI, is given more to conspiracy theories than analytical rigor. The defense secretary, Pete Hegseth, is a television personality overseeing chaos. And the Secretary of State and National Security Advisor, Marco Rubio, apparently forfeited his (considerable) expertise to please his boss. In any case, Rubio is not the one mainly dealing with Russia, Iran or Israel, say.

That would be Steve Witkoff, Trump’s all-purpose “special envoy” — not a diplomat, but a real-estate developer and Trump confidante. He’s now the president’s interlocutor with Russian leader Vladimir Putin (“I liked him,” Witkoff said after one visit). Stopping by the Kremlin the other day, Witkoff apparently didn’t bring a translator and relied on the Russian one. He either misunderstood or garbled Putin’s message; or he just became the latest victim of Putin’s KGB-style mind-manipulation. In any case, the resulting summit between Trump and Putin achieved precisely nothing.

Expertise without democratic accountability can lead to technocracy and a different kind of dystopia. But America’s strength has long been to balance both — the wisdom of impartial experts and the control of elected leaders. This gave the U.S. an obvious edge over its autocratic adversaries. American advisers, by and large, told their president the truth, especially when it was unpleasant. Their counterparts in Russia, say, instead tell their president whatever he wants to hear, leading to disastrous decisions such as the invasion of Ukraine.

Seven months into Trump’s second term, his administration now appears not just willing but eager to surrender this American advantage. And the first to feel the loss are the worker bees and drones inside the hives of American diplomacy and national security. Addressing them, William Burns, a former CIA director, laments that “you all got caught in the crossfire of a retribution campaign — of a war on public service and expertise.”

In the course of human events — at the courts of tsars, sultans, kaisers, shahs and the like — fealty has usually trumped expertise. The first surprise was that one major world power, by some accounts the greatest ever, became the exception and put expertise first. The second surprise seems to be that this same nation now voluntarily forsakes its superpower. If you happen to be in the Kremlin or in Zhongnanhai, that must feel satisfying.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering U.S. diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

Leave a Reply