Summer evening skies are the home of some classic constellations. One of them is Scorpius the Scorpion, the 10th-brightest constellation in the night sky and one of those few constellations that actually looks like what it’s supposed to be. Personally, I see Scorpius as a “giant fishhook” that trolls our low summer skies. You certainly won’t have to crane your neck to see it because it’s a low rider. Begin looking for Scorpius in the very low southern sky at the end of evening twilight.

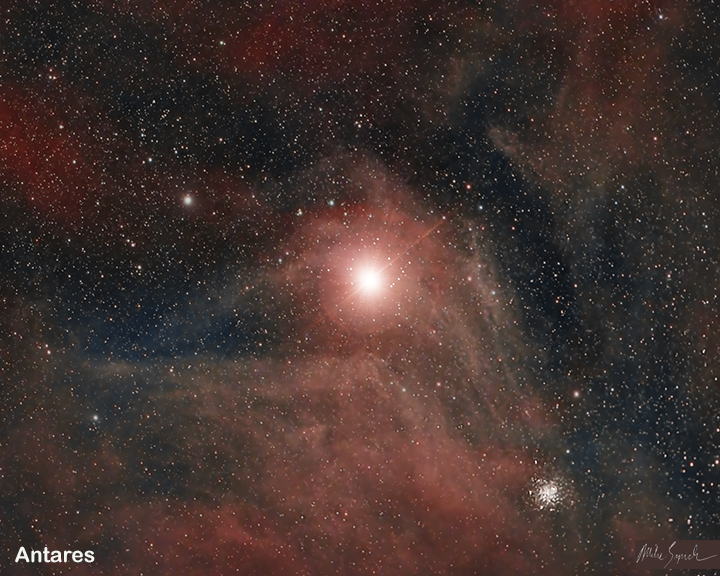

Most of Scorpius is easy to find. The brightest star is Antares, a brick-red star, marking the heart of the beast. It’s the brightest star in that part of the sky. To the right of Antares, you’ll see three dimmer stars in a nearly vertical row that make up the Scorpion’s head. To the lower left of Antares, look for the long, curved tail of the beast. Unfortunately, here in Minnesota and Western Wisconsin, the lowest section of the tail never gets above our horizon. At the end of the tail, barely above our horizon, is the celestial scorpion’s stinger, made of two moderately bright stars very close together.

(Mike Lynch)

The stinger stars, also known as the “cat’s eyes,” can be a bit of a challenge to see. You have to have a low, flat, treeless southern horizon to see them. Part of the difficulty of seeing the stinger stars is that visibility is greatly hampered close to the horizon because you’re forced to look through a lot more of Earth’s blurring atmosphere. Moderate to heavy light pollution and high humidity in the air can also add to the challenge. If you’re ever in the southern U.S., Scorpius will be a lot higher above the horizon, and you can get a much better look at it.

Antares (Mike Lynch)

Getting back to Antares, its reddish hue, demonstrates that stars come in different colors. They are not just little white lights in the sky. A star’s color tells a lot about its nature. Bluish-white stars are the hottest, with some having surface temperatures exceeding 30,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Reddish stars like Antares are cooler. In fact, Antares is cooler than our own sun, with a surface temperature of approximately 6,000 degrees. A thermometer plopped on the sun’s photosphere would show close to 10,000 degrees. Antares’ reddish hue is also reflected in its name. Antares is derived from the Greek language and means “rival of Mars,” as it shares a similar reddish tone with the planet Mars. You can easily confuse Mars and Antares with each other if you’re new to stargazing.

There’s no confusion between Mars and Antares when it comes to size. Mars is only about 4,000 miles across, a far celestial cry from the over-600-million-mile diameter of Antares. That’s over 700 times the diameter of our sun. If Antares were at the center of our solar system instead of our sun, the planets Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars would all be living inside Antares.

There are many stories about how Scorpius came to be a constellation. The one I like is the Greek mythology story about how Zeus, the king of the gods, sent a giant Scorpion to kill the mighty hunter Orion, to end an affair he was having with Zeus’ daughter Artemis, the goddess of the hunt. Orion hunted by night and slept by day, and while he was on his nocturnal hunting adventures, Orion was a hunk and caught the eye of Artemis. After watching Orion for a few weeks, she started to call down to the very manly hunter and have long-distance conversations with him every night. As time went on, Artemis eventually joined Orion in his hunting jaunts, ignoring her other duties.

Zeus learned of his daughter’s negligence and put a contract out on Orion. He had his staff send a giant scorpion to sting and kill Orion during his daytime slumber. When the fateful day arrived and the giant scorpion approached Orion, the ever-alert hunter awoke as the beast stirred the nearby brush with its approach. Orion shot up and valiantly fought the scorpion with all his might, but eventually he was stung by the steroid-enhanced scorpion and died instantly.

That night, Artemus discovered the body of her boyfriend and was filled with tremendous grief. She managed to compose herself and lift Orion’s body to the sky and transform it into the famous constellation we see during the winter evenings. As she looked back down to Earth, she saw the giant scorpion not far from where she had found Orion. She put two and two together and decided to get revenge. She dive-bombed the scorpion, picked it up, and flung it up into the opposite end of the sky from her dead boyfriend, where it transformed into a constellation. That’s why the constellations Orion and Scorpius are never seen in the sky at the same time. Orion prowls the winter skies and Scorpius trolls the summer heavens. Orion won’t get stung again.

Celestial happening this week

(Mike Lynch)

On Sunday and Monday, toward the end of evening twilight in the very low western sky, look for the new crescent moon hanging close by the faint planet Mars.

Mike Lynch is an amateur astronomer and retired broadcast meteorologist for WCCO Radio in Minneapolis/St. Paul. He is the author of “Stars: a Month by Month Tour of the Constellations,” published by Adventure Publications and available at bookstores and adventurepublications.net. Mike is available for private star parties. You can contact him at mikewlynch@comcast.net.

Related Articles

Skywatch: The swan of summer is flying high

Skywatch: Lyra weaves quite a tale

Skywatch: Shooting the moon

Skywatch: Full-blown July summer skies

Skywatch: The “Z” stars, tongue twisters of the night sky

Leave a Reply