Jonelle Madera has experienced a lot of change in the last school year.

The elementary school teacher and mother of four left her home country of the Philippines for the first time, moved to the U.S. and began what is expected to be at least three years working as a special-education teacher with St. Paul Public Schools.

She wondered if she’d be understood. Would people get her jokes and could she just be herself?

“And some would say, ‘Oh, my God, you have a family to leave, how can …’ you know?” Madera said. “We see things differently, and not everyone (gets) the reason why you’re leaving your country for your dream. But you know, my dream is also for my family’s family. And it’s great to see the world.”

Madera is one of 19 special-education teachers in the district this school year recruited from the Philippines, one measure in response to a number of unfilled special-education positions in the district and part of a larger shortage of teachers nationwide.

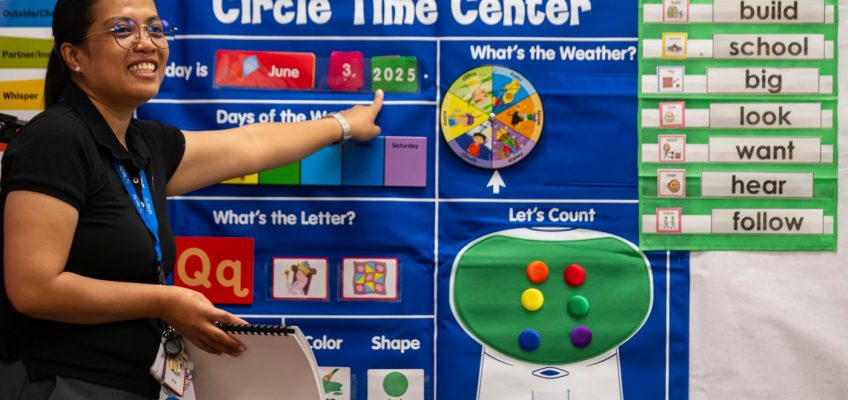

Jonelle Madera, a special education teacher at the Heights Community School in St. Paul, coaxes a answer from a student on Tuesday, June 3, 2025. (John Autey / Pioneer Press)

“Special education has been experiencing pretty significant workforce shortages, specifically in regards to special-education teachers,” said Heidi Nistler, SPPS assistant superintendent in the Office of Specialized Services. “It’s always been an area where it’s difficult to find highly qualified and experienced candidates. But I think kind of coinciding with the pandemic, their workforce shortages essentially reached crisis level, and a few districts elsewhere in Minnesota started to explore recruiting international teachers.”

At the same time, SPPS officials heard positive things from other districts about recruiting internationally. The district began to look into the possibility about a year ago. In St. Paul, the first Filipino teacher arrived Thanksgiving Day and the last one in March.

‘It’s my dream’

Madera, along with the other Filipino teachers in SPPS, is on an H-1B visa. That’s the case for most of the teachers recruited by PhilAm Partners LLC, a consulting agency based in Fargo, N.D., that recruits Filipino teachers to work in American school districts, and worked with SPPS.

The biggest need in the U.S. seems to be special-education teachers, who make up the majority of those PhilAm recruits, said Dan Johnson, who, along with his wife, Claire — herself a former teacher from the Philippines — owns PhilAm.

The H-1B visa allows visa-holders to work in specialty occupations in the U.S. for up to three years and can be extended for another three. With an H-1B visa, costs can approach around $10,000 per teacher. A smaller number of districts opt for J-1 visas, which are considered an exchange visitor visa and typically for a shorter term.

On the district side, teachers follow the same process any other teacher applying to the district goes through, said special-education supervisor Carolyn Cherry, and their credentials are evaluated to determine their U.S. equivalent. Districts also let PhilAm know what skills and backgrounds they are looking for.

For PhilAm, teachers typically need to have at least three years of experience and a proficient level in English, Johnson said, though many already have decades of experience or advanced degrees. Teachers who have previous experience teaching in the U.S. are also preferred, though that still remains a smaller number.

PhilAm has brought more than 200 teachers to North Dakota and Minnesota since it began in 2022, with around 175 in the Twin Cities metro area.

“We want to make sure that we’re bringing people that are ready and interested, have a high interest. I’ll tell you this, when I pre-interview, almost all of them say, ‘It’s my dream,’” Johnson said.

The state Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board also reviews and awards each candidate a Tier 3 or 4 teaching license, Nistler said.

Teachers attend a pre-departure seminar as well as an orientation seminar put on by the Filipino embassy after arrival. With those, as well as orientations from PhilAm, they learn about professionalism in the U.S., culture, safety and finances.

The Johnsons also strongly encourage districts to have the basics prepared for the teachers. For Madera, that meant SPPS’s Cherry picking her up from the airport and then staying with the family of an SPPS teacher while she looked for an apartment. She now lives with three other Filipino teachers in the district.

While PhilAm’s clients are the districts, the Johnsons work to be a consistent point of contact for teachers throughout their time in the U.S.

“These are professionals, so we want to – this is our goal – is to give them independence. And not everyone’s going to be the same. Some need more guidance. Some just take it and run. Some we don’t need to hear from too much, and they just go and they do their own thing. And that’s really exciting for me, quite honestly,” Johnson said.

Other Filipino teachers tend to pay it forward, too, Johnson said.

“They really open up and they’ll even do some of the things that the district normally would be doing. For instance, taking them to get a Social Security number, so they might even bring them to an appointment, or to get a phone or certain things like that,” he said.

While most of the districts that PhilAm has worked with are in the Twin Cities metro area, they have also worked with districts in Alexandria, Moorhead and Faribault, as well as private and charter schools.

Special-education vacancies

SPPS has around 6,000 students who receive special-education services. Around 2,000 staff work in special education, which includes almost 500 special-education teachers, in addition to speech-language pathologists, social workers, occupational therapists and paraprofessionals.

But in the last few years, the district has struggled to find enough candidates for open positions in special education.

“So that has just persisted for the last couple of years, and really the impact is on our students who may not be getting the services that they need,” Nistler said. “So that’s why special education is such a high priority, and why, when we’re talking about these innovative types of programs, it’s focusing on special education because we have a legal and ethical responsibility to be providing services to make sure that our students with disabilities have their needs met in school.”

There have been a variety of strategies across the state to address shortages, such as grants under the state’s Special Education Teacher Pipeline Program for those pursuing careers as special-education teachers.

“There’s been other programs that are all working to address the workforce shortages, but those efforts haven’t been enough to fill the positions that are currently vacant, which is why we started to explore the international teachers in conversations with other districts who had started this work earlier than us,” Nistler said.

Those shortages have meant more responsibilities for the special-education teachers the district does have.

“And so as much as possible, the other educators and others try to provide the services and complete all of the paperwork to ensure that students are still receiving what they need,” Nistler said. “But there are times that we just haven’t been able to find somebody to provide those services and then we work with families to try to make up for those services at a later time. But we really want to make sure we are providing the services when the students need them during the school year, during the school day.”

Meanwhile, state lawmakers included $4 million in their most recent education bill for a special-education apprenticeship program to recruit and retain teachers with past experience. At the same time, lawmakers set up a commission to find $250 million in cuts by the next session for special education for the 2028-29 budget.

With teachers like Madera in the classroom, districts are able to close some of the workforce gaps.

“I think a year ago, the number of vacancies we had for our special-ed teachers was over 30. Whereas right now, we have fewer than 10 current vacancies in the current school year,” Nistler said last month.

A learning curve

With the school year over, Madera is staying in the U.S. to continue working for SPPS this summer. Despite the distance from her home country, Madera is finding community, from the paraprofessionals in her classroom who remind her they are a team, to other Filipino teachers who have helped her with classroom setup or dressing up for an interview.

“I am really surrounded with the kindest people. From home to school, I am surrounded with the kindest people, and I’m so grateful for that,” Madera said.

It can be a learning curve, from working with district iPads and students’ assistive devices, to following new curriculum, and doubts can come up, but Madera pushes through.

“How am I going to communicate with this child? Will he be able to understand me? Will I be able to understand him? But if you have the love for your learners, I guess you can do anything,” Madera said.

Related Articles

St. Paul school board OKs $1 billion budget for 2026

St. Paul Central students design a mascot to represent everyone

St. Paul’s Maxfield Elementary breaks ground on ‘community schoolyard’

SPPS: New Superintendent Stacie Stanley begins first week with district

St. Paul Public Schools narrows achievement gap in 2024 graduation rates

Leave a Reply