St. Paul police detective James Crumley made an unsettling discovery in early 1935.

A small dictograph microphone hidden in his office had been recording Crumley’s conversations with colleagues and visitors.

It was one of several bugs hidden throughout police headquarters by 27-year-old Wallace Ness Jamie, a private investigator hired by the St. Paul Daily News to expose corruption within the department.

The editor of the Daily News had convinced the city’s public safety commissioner to let Jamie bug the building and tap its phone lines. The conversations he collected revealed that some of the department’s top cops were accepting bribes to protect illegal gambling and prostitution rings.

Crumley, who played a key role in this web of corruption, was one of more than a dozen officers ousted or suspended when the story broke that summer — including the chief of police.

“It was one of the greatest moments of journalism history in Minnesota,” said Paul Maccabee, whose book “John Dillinger Slept Here” chronicles the city’s Prohibition-era crime wave. “They brought down three-and-a-half decades of police corruption in just a few weeks. It was remarkable.”

In the years that followed, a raft of ethics reforms was imposed on the department by city officials, increasing oversight and depoliticizing the hiring process for the city’s police chief, Maccabee said.

By 1941, the FBI gushed that St. Paul had “one of the best and most efficient police departments in the United States.”

The O’Connor System

The brazen corruption that pervaded St. Paul’s police force in 1935 didn’t spring up overnight.

Criminals had long known that — for a price — its officers were happy to let them lie low in town, as long as they did their robbing and killing outside the city limits. This handshake agreement was born under Police Chief John J. O’Connor, whose tenure at the top of the department began in 1900.

St. Paul Police Chief John O’Connor welcomed criminals to town during his tenure — as long as they behaved within city limits. (Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

“If they behaved themselves, I let them alone,” he said, according to a 1951 article in the Pioneer Press. “If they didn’t, I got them.”

Under the system of graft O’Connor devised, out-of-town crooks checked in with an underworld go-between, who would collect their name, address and a cash bribe. Their money, along with similar “taxes” from the owners of St. Paul brothels and casinos, ended up in the pockets of O’Connor and other local officials.

“The people of St. Paul knew that the O’Connor System was in place,” Maccabee said. “That’s the amazing thing about this: It wasn’t a secret. It was openly discussed.”

As long as it kept the city’s streets relatively free of major crime, St. Paulites seemed to accept this arrangement, according to Maccabee. But cracks began to appear when O’Connor retired in 1920, just as Prohibition offered a lucrative new income stream to the city’s criminals.

“The O’Connor System was an important part of why St. Paul became so corrupt, but Prohibition definitely lit the fuse on the worst of the corruption,” Maccabee said.

When Prohibition was finally repealed in 1933, the city’s criminals were forced to find new ways to make a buck. They turned to kidnapping, bank robbery and illegal gambling.

‘Machine guns blaze’

St. Paul tried to shake its reputation as a haven for criminals in early 1934.

After two of its wealthiest businessmen, Edward Bremer and William Hamm Jr., were kidnapped for ransom by gun-toting gangsters, the city’s embarrassed mayor impaneled a grand jury to investigate whether Minnesota’s capital had a crime problem.

The front page of the March 31, 1934, issue of the St. Paul Daily News reported that gangsters had shot their way out of a Lexington Parkway apartment building the same day that a grand jury found that no “excess of crime exists here.”

Three months later, the grand jury published its conclusion that “there is no justification for any charges that an excess of crime exists here.” That same day, famous fugitive John Dillinger shot his way out of a Lexington Parkway apartment complex to escape capture by federal agents.

“MACHINE GUNS BLAZE AS JURY WHITEWASHES POLICE,” screamed a headline across the front page of that afternoon’s edition of the Daily News.

Its editor, Howard Kahn, had been waging a lonely campaign against St. Paul’s lawlessness for months. His scathing editorials targeted not only the city’s criminals, but also powerful public officials who turned a blind eye to them.

“He was ridiculed for it,” Maccabee said of Kahn’s anti-crime crusade. “He had a lot of guts.”

But now it seemed St. Paulites had finally come around to Kahn’s point of view. Later that year, they elected reformer Ned Warren as public safety commissioner on a promise to “clean up” the police department.

Shortly after he took office, Warren agreed to let Kahn embed Jamie in the city’s new Public Safety Building — now the Penfield apartment complex — to collect evidence against its corrupt cops.

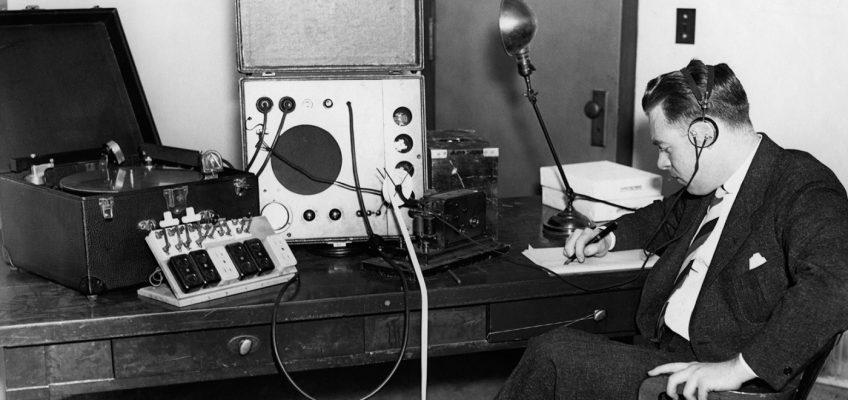

Jamie had studied criminology at the University of Chicago and Northwestern before going into business as a private investigator, and he employed the latest electronic surveillance tools in his work for Kahn and Warren.

Cleaning house

In early 1935, Jamie and a handful of assistants set up shop in Room 201 of the Public Safety Building.

They posed as bureaucratic number-crunchers conducting an “administrative survey” of the police department’s crime statistics on Warren’s behalf, the Pioneer Press later reported.

“He drew a bunch of diagrams … and the cops looked at them and laughed behind his back,” Kahn said of Jamie. “They called him a dumb college boy.”

The surveillance team operated in secret for four months before Crumley discovered the bug in his office and warned his corrupt colleagues to watch what they said, according to the Daily News. By then, Jamie and his assistants had already filled 400 aluminum phonograph records with incriminating conversations.

In one typical recording, detective Fred Raasch was caught telephoning the proprietor of the Riverview Commercial Club to warn him of an imminent police raid on its gambling operation.

“Take the two slot machines down,” he said. “There’s a couple of guys coming right over.”

In another, Crumley called a bookie at the St. Paul Recreation Co. to ask why it had been so long since he had received a bribe.

“Say, when are you going to play Santa?” he asked. “We’re all broke up here.”

Warren submitted Jamie’s findings — including 3,000 pages of surveillance transcripts — to St. Paul Mayor Mark Gehan on June 24, 1935, implicating 13 officers in the corruption scheme, according to Maccabee. The department’s chief was suspended and would soon resign.

The front page of the June 24, 1935, issue of the St. Paul Daily News announced that several of the city’s top police officials had been caught up in a wiretap sting.

Kahn splashed the story across the front page of the Daily News that afternoon, proudly detailing his newspaper’s involvement in “the most drastic shake-up in the city’s history.”

As acting police chief, Warren installed a by-the-book cop named Gus Barfuss, who would soon replace him as public safety commissioner and carry on his campaign to inoculate the department against corruption.

A 1941 FBI survey of crime conditions in Minnesota found that Barfuss “has ‘cleaned out’ the St. Paul Police Department.”

The department remains committed to keeping it that way today, spokeswoman Alyssa Arcand said in an email.

“The St. Paul Police Department does not tolerate corruption of any kind,” she wrote, adding that a peer intervention program instituted in 2021 teaches the city’s police how to recognize and address unethical behavior in their fellow officers.

This kind of vigilance is vital at a time when illicit drug markets offer the same opportunities for graft that the illegal alcohol trade did a century ago, Maccabee said.

“There’s no question that the St. Paul Police Department is radically different today than it was then,” he said. “Yes, this is history. But we shouldn’t get complacent.”

Related Articles

‘Jaws’ sank its teeth into Twin Cities moviegoers 50 years ago

Hortman began legal career with win in landmark housing discrimination case

Marine of Minnesota’s ‘Twins Platoon’ details legacy of Vietnam in new book

Downtown St. Paul has been declared ‘dead’ before

Photo Gallery: George Floyd’s murder shook Twin Cities five years ago

Leave a Reply