“It was more important to Tom to be right than to be famous — ‘right’ meaning not just factually accurate but also morally correct. Tom was not a prophet or zealot; he lived in a complicated city like the rest of us. But he knew that when encountering moral ambiguity, you had to think harder, not just throw up your hands.”

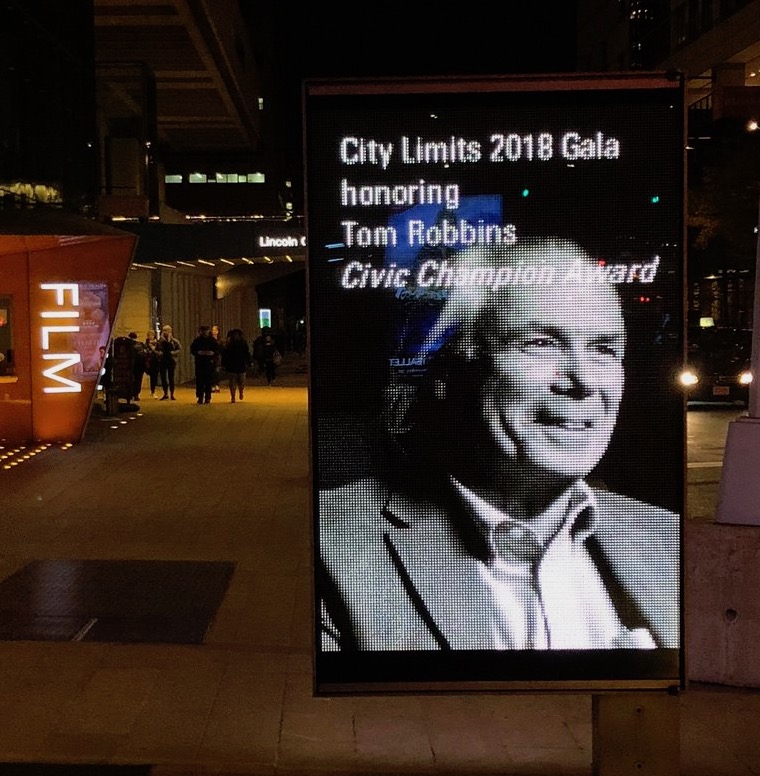

City Limits honored Tom Robbins at the newsroom’s anniversary celebration in 2018. (Photo by Adi Talwar)

On the day after the night when Tom Robbins died it rained in New York City. The rain was gentle but steady.

It rained on yellow cabs and for-hire cars driven by people trying to make it through traffic, and trying to make it, period. The water coated the places of power, like City Hall, the courthouses and the anodyne headquarters of bureaucracies. It was raining in the recreation yards of jails while roofs leaked in buildings owned by negligent landlords.

Puddles formed around the graves of the wrongfully dead, and the grass muddied near the tombs of the gangsters who killed them. On construction sites people toiled in the rain and in homeless encampments they hid from it. Tenant organizers and social workers looked out windows streaked wet, then went back to work. Reporters typed against the rhythm of the drops and sipped lukewarm coffee.

The rain fell on the depraved and the noble, on the victims of sweeping injustice and the dispensers of minor mercies, on heroes and nobodies, because even in a place as vast as New York City, there are inescapable truths, no matter your ZIP code, where you went to school, your immigration status, whom you know.

Yesterday that truth happened to be rain, but there are many other truths. Tom knew them. And he wrote them down.

One such truth is that a New York City built for the working class, a place where everyone gets treated with dignity at work and makes enough to afford a decent life, is a thing we could have and is worth fighting for, no matter who dismisses such notions as radical or nostalgic. Tom believed and struggled for working-class New Yorkers his entire adult life. He skipped college and drove a cab before getting canned for trying to unionize the drivers. Then he organized tenants working to salvage a decent place to live in a crisis-ravaged city. Finally, he turned to a typewriter to try to change the world.

That turned out to be a good move. Tom’s stellar career, as the great tributes this week by The Times, The City and others will tell you, took him from a stint as editor of City Limits to the Village Voice, the Observer, the Daily News, and back to the Voice, before he shifted to teaching at the CUNY Newmark Graduate School of Journalism, penning investigative projects for the Times and the Marshall Project, writing for The City, and most recently hosting a terrific show on WBAI. He wrote a book, nabbed snazzy awards, chased scoundrels from power, delivered justice to the imprisoned and taught generations of young reporters what it meant to cover New York.

Tom Robbins, right, with former City Limits’ editor Jarrett Murphy

in 2018. (Photo by Larry Racioppo)

Through it all, Tom seemed like the last of a bygone era when newswriting was a trade and its practitioners brought blue-collar sensibilities to their coverage of the city. He did not dress particularly well. But he wrote clearly and powerfully, a true craftsman, erudite but never showy. Colleagues of Tom’s will remember that one of the sounds of deadline day was the low rumble of him reading his story to himself before he turned it in, so he could make sure it sounded right.

Despite his immense skill and accomplishments, Tom during his life might not have earned the accolades or attention that some of his fellow New York City columnists enjoyed. In part that is because of the outlets where he worked and the types of stories he pursued, which often did not lend themselves to glamor. It is also explained to some degree by the fact that the news business is, to quote a Robbins understatement, “lousy.”

Most important, however, is the fact that Tom’s journalism was never about Tom, not in any sense or dimension. He didn’t seek the limelight, often eschewed credit, even got irritated when people revealed his acts of singular generosity. When the Village Voice fired his great friend Wayne Barrett and Tom told them to fire him too, he hoped the act of solidarity would be low-key. He didn’t want to play the martyr. He knew the truth: that, in the end, it is much more valuable to be a friend.

More broadly, it was more important to Tom to be right than to be famous—”right” meaning not just factually accurate but also morally correct. Tom was not a prophet or zealot; he lived in a complicated city like the rest of us. But he knew that when encountering moral ambiguity, you had to think harder, not just throw up your hands. Tom never gave up on the truth that unions are essential for making sure working-class people get the decent life they deserve. He helped lead the Village Voice union through one of the most contentious contract negotiations in history, when it came so close to a strike the staff had printed all the picket posters.

Yet Tom’s faith in the idea of organized labor never blinded him to the rampant corruption in many of the organizations that purport to represent workers, and he often exposed their thieving. His commitment to justice led him to the painful decision in 2007 to break a promise to a source and reveal that she had lied on the stand in the trial of a corrupt FBI agent. Saving a mobbed up G-man from a lengthy prison sentence was the last thing Tom wanted to do, but it happened to have been the right thing, so he did it.

That combination of skill, modesty and moral compass gave Tom a quiet strength. He knew what he’d come for and didn’t need to shout or throw chairs to show he belonged there. While he was certainly no pushover, and could make it sufficiently clear that he thought you’d done something wrong (full disclosure: Tom was angry at me for about the first three months we knew each other), he didn’t bluster or humiliate, intimidate or threaten.

In a big-city political arena where alpha males throw their weight around, he wore a wry smile and a blazer, neither taking the bait nor backing down. He knew that kindness and optimism were journalistic assets, not handicaps. Keep asking questions. Keep reading documents. Believe in the story, even if no one else does. Believe in a better world, even if it seems to be slipping away. Like water, just keep coming, constant, undeterred, unfazed.

Tom Robbins and Annette Fuentes in City Limits’ offices in the early 1980s. (Photo by Brian Patrick O’Donohue)

This is an inopportune moment to lose Tom’s voice, what with cruelty and avarice becoming national policy, cowardice infecting our institutions, unrepentant venality clinging to power in City Hall, the free press under relentless attack everywhere. I don’t know where Tom would have directed his reporting this week if he were still out there. Maybe he’d be at Federal Plaza, where federal agents are arresting New Yorkers playing by “the rules” and showing up for their immigration hearings. Or perhaps he’d be out on the campaign trail, to keep an eye on the municipal candidates bankrolled by casinos and Big Tech. It’s anybody’s guess; the guy was pretty nimble.

But one thing I know for certain is that he would care, and he would try. None of us has an excuse to do less.

Yesterday it rained on all the city Tom Robbins tried to help, and did, across 40 years of journalism—on people who never read his work, but were on his mind and in his notebook, and places he chronicled in front-page articles and forgotten news briefs. It rained on the decent and kind New York he tried to save and embodied. It rained a little today, too, as a matter of fact.

Jarrett Murphy met Tom Robbins in 1999, worked alongside him at the Village Voice, and stood on his shoulders as editor of City Limits from 2010-2020. He’s now a pediatric ER nurse in Manhattan.

The post Tom Robbins and the Truth appeared first on City Limits.

Leave a Reply