Clinton Young stepped out of the Midland County Jail, the way station between his previous address for the last 18 years and the free world, on the afternoon of January 20, 2022. He’d been anxious all day, sitting in the cell block with an ankle monitor already affixed to his leg, awaiting release on bond.

When he finally exited the building, he hugged his little sister—now a woman in her 30s—for the first time since she was 11. Their last hug had taken place when Young was 19 years old, and on trial for capital murder.

It was below freezing in West Texas, but Young wasn’t worried about the temperature. Even as he greeted his family and supporters, he was already fixated on time: He figured he should leave the jail as soon as possible in case authorities changed their minds.

After all, Young’s home for nearly two decades hadn’t been a house or even a typical prison cell. He’d been kept in isolation after being sent to Texas’ death row, a Midland jury having weighed the likelihood of his “future dangerousness” and determined—based on his alleged crimes and conduct—that the state should execute him because he was too dangerous to be allowed to live.

Young had two hours to shop for clothes and other necessities before he needed to be at the Midland apartment where he’d been approved to stay. At the mall, the open space and throngs of people didn’t bother him, but he sped through anyway—grabbing duplicate pairs of jeans without much thought, as if prison guards or police were in pursuit. He knew already, as he puts it, that the eyes of Texas were upon him.

He made it to the temporary apartment in time, even after a wrong turn that could have raised alarm bells for anyone tracking his ankle monitor. After hours of disbelief, hurried reunions, and apprehension, the tension began to dissipate.

“41 YEAR-OLD ME WOULD NEVER MAKE THAT DECISION THAT 18-YEAR- OLD ME MADE.”

Then 38, Young had not been in the free world for decades. He’d been convicted in 2003 following the 2001 shooting deaths of two men, Doyle Douglas and Samuel Petrey, in Midland and Harrison counties. According to the state, Young and three other young men were involved.

Young has always maintained he was not the shooter in either case. But, in Texas, Young could be sentenced to death without ever pulling a trigger, based on the so-called “law of parties.”

Under the law, juries can convict someone of capital murder if they believe that person was involved in planning or carrying out a crime—such as robbery—and should have known someone could die in the process. In Young’s case, only he was tried for murder, while the others allegedly involved testified against him and received lesser sentences for their parts in the crimes. Two accepted plea deals: Mark Ray was convicted of second-degree kidnapping and was sentenced to 15 years in prison, and David Page got 30 years for aggravated kidnapping. Darnell McCoy, who, according to court documents, was present at the first murder, was not charged.

As Young’s appeals made their way through the courts, he slowly gained international allies. In 2014, advocates in the Netherlands who’d learned about his case and considered his sentence unfair launched the Clinton Young Foundation. That foundation would be instrumental in backing his legal fight—and supporting him during his time on bond.

Over time, Young’s case gained even more attention because of the bizarre misconduct of one prosecutor. In 2021, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA), the state’s highest criminal court, threw out his 2003 conviction after the Midland County District Attorney’s Office revealed that, during Young’s trial, its employee Weldon “Ralph” Petty Jr. had been quietly working for both the prosecution and the judge. Petty, while working on cases including Young’s, drafted judicial opinions and orders that agreed with his arguments, often getting them rubber-stamped by the judges. He held these dual roles for nearly two decades. Only after he left did the DA’s office finally tell Young’s defense lawyers about this long-hidden conflict of interest.

Petty’s misconduct sullied the case against Young, who’d come within eight days of an execution in 2017 before receiving a stay from the CCA. In October 2021, a month after the CCA ultimately vacated his conviction, he was transferred from death row to Midland County Jail, where, after a three-month stay, he was ultimately released on a $150,000 bond, pending word on whether he would once again be tried for capital murder.

Young knew he had won release against extremely long odds: Since 1977, the Death Penalty Information Center reports that 18 Texans formerly on death row have been ordered released and won their freedom. Four were acquitted, while the rest saw charges dismissed based on overzealous prosecutions, inadequate evidence, ineffective defense, or flawed forensics.

Still, Young hoped that, during his time as a free man, he could demonstrate he’d changed. He aimed to prove he no longer presented the threat of “future dangerousness,” a legal requirement for the Texas death penalty. He wanted to establish that he wouldn’t squander his second chance at life.

“Death row becomes what prison is supposed to be but often isn’t,” Young mused to the Texas Observer in a January letter. “Death row is a place of reformation, rehabilitation, and correction. Ironically the one place where it matters the least.”

In the years Young spent in a high security prison in Livingston, 274 people were executed by the state, while 183 new people were condemned by Texas juries.

In the last half-century, approximately 300 former death row occupants have had their convictions overturned or sentences reduced to life or even a lesser sentence, according to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. But rarely were these people released on bond while the courts worked out their cases.

On that January day, Young became an outlier, an exception to the rule, which states that the main exit from Texas death row is through lethal injection.

“I made a little video of me touching grass,” Young told the Observer in a January interview. “But unfortunately, I was in West Texas, so the grass was dead. It was kind of anti-climactic.”

Young spent about a month in his Midland County apartment, his rent funded by the Dutch foundation, determined to successfully navigate his early days of freedom on his own.

Then, he got permission to return home—to East Texas’ Marion County, where he was raised and near where one of the two killings that changed his life took place. He temporarily moved in with his younger sister, Jessi Gonzalez, about 20 minutes from the tiny town where both grew up. Gonzalez watched her three sons—now 17, 12, and 9—develop a relationship with the uncle they’d only seen during prison visits.

“I’d seen my nephews grow up behind glass,” Young told the Observer. He said he enjoyed “the little stuff” he’d missed like playing video games, which required a crash course since they’d grown much more sophisticated in two decades.

The family settled into as comfortable a routine as possible in close quarters. Young got his driver’s license, played with his nephews on the trampoline and zipline in the backyard, and helped with household chores.

He and Gonzalez tried to navigate the sudden rekindling of their day-to-day sibling dynamic. They had grown up together until Young, as a teenager, was taken into custody by the Texas Youth Commission for juvenile offenses. Gonzalez said her brother has always been energetic, having trouble sitting still. He’s extremely intelligent, and he knows it: “Hard-headed,” Gonzalez fondly calls him. “Sometimes you can’t win with him,” she laughed. “He’s gonna be right.”

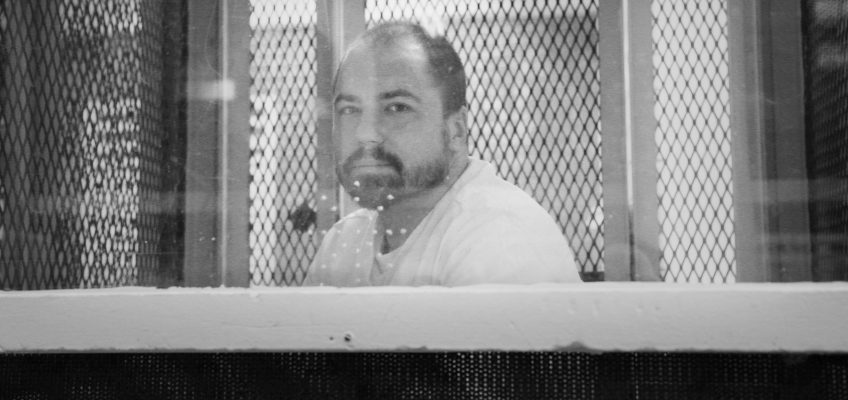

Young in a prison visitation booth (Michelle Pitcher)

After a few weeks, Young moved back to their childhood home nearby. The cedar-and-log house with a green metal roof that Young’s parents built had been expanded and renovated. But his parents, with no children at home, had moved and left the big house empty. Lake O’ The Pines is visible from the porch. Young could take in the view, but he still wore the ankle monitor, which at first only allowed him to go up to 100 feet away from his house. He could see the water, but he couldn’t reach it without tripping an alarm.

Young set himself up in the living room, the largest space, after too many years confined to a cell. He pushed the couch up against the back wall, and he spread out his things.

Alone again, he noticed that the place held ghosts. “I can’t say I had a lot of good memories as a kid,” he said. This particular homecoming “wasn’t really a joyful experience.” He also worried that unwelcome people from his past—those he knew when he was involved in crimes as a juvenile and young adult—might arrive.

“They’re still stuck 20 years ago, and that’s how they still picture me,” he said. “They don’t know the man who’s had an execution day [and] dealt with people all over the world. My world views have changed drastically.”

Young got a job with an oil and gas company. He was able to move around more for work, and he began to earn money. He eventually switched to a larger company, which paid for him to get his commercial driver’s license. It was a well-paying gig, with health insurance, and he could cross state lines while working. He still feared his time as a free man might be limited, but each day on the outside took him one step further from death row.

In August 2022, he and some coworkers cut through Mississippi on their way to a work site in southeast Louisiana. They’d stopped to get something to eat, when their work trucks were surrounded by police cars. Young’s coworker turned to him and said, “Man, I think they’re here for you.”

Young, it turned out, had been indicted by a special grand jury in Harrison County for capital murder for one of the 2001 fatal shootings. The new indictment came as a shock. Young had previously been tried for both cases only in Midland County.

“I was living good,” he told the Observer. “Everything was great. I had shaken off the side effects of prison and solitary confinement for the most part. And then, boom.”

Young was jailed for two weeks in Vicksburg, Mississippi, far from his home and job. The judge initially set bail at $5 million, but his lawyers got it reduced to $150,000, the same amount as his original bond. That meant his supporters, who were already helping to pay his legal bills and had secured prominent criminal defense attorney Dick DeGuerin to represent Young in his retrial, had to raise more funds.

Eventually, they secured enough donations and paid the new bail—all $150,000 in cash—and Young was once again released on August 29, 2022.

He returned to work in the oil fields. Juan Gonzalez, Young’s supervisor for several months in 2024, called Young a hard worker who spoke openly about his life. “I believe that what he was accused of just can’t be him,” Gonzalez told the Observer in December. “He is a well-spoken, very smart guy. Good attitude, always a little smile on his face.”

Young began to see a therapist at the suggestion of a judge and his own attorneys. He found a post-traumatic stress specialist who had done time in federal prison, and he saw him for several months.

To his supporters, Young was doing surprisingly well in his years as a free man after so long behind bars. DeGuerin, who’s practiced criminal law for nearly 60 years, said many people in prison with extreme sentences become “defeated” and lose initiative.

“But Young used that time to educate himself,” DeGuerin told the Observer. “He spent 20 years locked up, and all of a sudden you can see the sky and you can walk barefoot on grass. It’s a completely new experience. It’s impressive to me that he was able to handle that.”

While out on bond, Young advocated for others on death row. In February 2023, he testified in front of the Texas House Committee on Criminal Jurisprudence about the death penalty appeals process. In November 2023, he participated in the Annual March to Abolish the Death Penalty in Austin. “Why I do everything is to be heard, to convey my sense of what’s right,” Young told the Observer.

“MY WHOLE MINDSET HAS ALWAYS BEEN LIKE, ‘Y’ALL AIN’T GONNA BREAK ME.’”

He filed a lawsuit against Midland County officials, including Petty, whose conflict of interest had led to Young’s conviction being reversed. His lawsuit is temporarily stayed while Texas courts wait to see if the U.S. Supreme Court will take up a similar case stemming from Petty’s misconduct.

“The thing I’m most struck by is the fortitude of [Young’s] spirit,” attorney Alexa Gervasi, who’s representing Young in his civil case, told the Observer. “He is still fighting and he’s not giving up.”

Young had found love, too. In the heady early days of freedom, he began a romance with a friend, got married, and on a stormy night in March 2024—26 months after his release—he became a father.

He drove his wife to the hospital in heavy rain, his hazard lights flashing and four-wheel drive engaged. The birth wasn’t smooth—the doctors had to perform an emergency caesarean, and the baby was born with fluid in his lungs. The newborn spent time in a neonatal intensive care unit. It was a tense period of waiting, hoping for an outcome almost too precious to imagine—a supremely anxious desire for life somewhat akin to the hope Young had experienced before his release. The baby boy was eventually released to Young and his wife, who asked not to be named to maintain their son’s privacy.

“My son is going to break the cycle,” Young said. “My son is not having the life I have. My biggest concern is protecting my son. … When people see him, they’re not going to think ‘Clinton Young’s son.’ He’s gonna have his own identity, his own life.”

While Young charted his new path as a free man, and a father, preparations for his return to court were underway. In fact, the process had begun before he ever stepped foot out of the Midland County Jail. Shortly after his release, the state attorney general’s office took over his case and began planning its strategy for reprosecuting the now decades-old crimes.

In October 2023, state lawyers attempted to revoke Young’s bond because he had visited old friends who had also been released from prison and were affiliated with a prison gang in which he’d once been active. Young told the Observer he joined the gang when he was in the juvenile justice system, looking for belonging and security, and that “41 year-old me would never make that decision that 18-year-old me made.” Young is no longer affiliated with the prison gang, and he got his tattoos removed while out on bond.

Young’s new Midland County trial, independent of the surprise Harrison County indictment, was slated for October 2024. By then, he would have shown for nearly three years that he could be a productive member of free society. Young believed that the state’s case against him was thin, but he’d sat at the defense table before, and he knew what could happen once a trial got underway.

The state was originally planning to seek a new death sentence, but in late 2023 prosecutors announced they would pursue a life sentence instead for only one murder. Because Young was being tried for a crime that took place in 2001, before life without parole was available in Texas, a life sentence with the possibility of parole was the harshest penalty a jury could impose.

During the trial, the public seats in the courtroom weren’t packed, despite the notoriety of Young’s conviction reversal, and the retrial proceeded relatively quietly.

The state presented much of the same evidence it had at the original trial, including testimony from one of his co-defendants. The original trial testimony of one now-dead witness who claimed he’d interacted with Young the night of the murders—but who had recanted in the years since—was entered into evidence without mention of the reversal.

Young, who’d been optimistic prior to trial, knew that when the jury members left the courtroom to deliberate, they would likely vote to send him back to prison for life.

As they weighed his fate, Young stepped outside the courthouse and smoked a cigarette, replaying the trial in his mind. He knew some people expected him to flee, but even if he somehow escaped, he would never again see his son, who’d crawled for the first time the day prior. Young had spent the past few years trying to show people that reform and rehabilitation were possible, and he didn’t want to jeopardize that.

“The hardest thing I did in life was turn around and walk back in that courtroom,” Young told the Observer. “I wanted to show that people aren’t what you make them out to be. You don’t have to kill us. You don’t have to throw us away for the rest of our life. We’re capable of changing and making the right decisions in life.”

Young kisses his son. (Courtesy/family)

The jury convicted Young once again for the 2001 murder in Midland County of Samuel Petrey, this time sentencing him to life in prison with the possibility of parole. He may face another trial for the Harrison County murder, the result of the indictment he received while out on bond.

After hearing the verdict, Young tried to look calm for his family and supporters. But the mask fell when he was handed his baby boy. Young knew he wouldn’t be considered for parole for years and might never be free again.

“My whole mindset has always been like, ‘Y’all ain’t gonna break me,’” he told the Observer. “When I said goodbye to my son in that courtroom, I broke.”

Within 48 hours, Young was back in the custody of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. In November, just a month later, he began a blog post, published with the help of the foundation, with his trademark humor. “Now as I was saying: before being interrupted by freedom, life and more legal drama. The problem with the justice system is…”

When he spoke with the Observer in January, he wore the standard-issue white uniform, and he had the grown-out buzz cut and light facial hair worn by so many others housed at the massive Coffield Unit in Anderson County, southeast of Dallas. Yet, he smiled through the conversation, cracking jokes and speaking with an easy candor. He teared up only when asked about his son. He sees him every week, but he’s not allowed to touch him or his wife; he has no-contact visits, given his current custody level.

Young continues to pursue legal appeals and to advocate for those still on death row. “The fight goes on,” he said, just a few minutes before prison officials announced the interview was over. “I got nothing but time.”

The post ‘You Don’t Have to Kill Us. You Don’t Have to Throw Us Away.’ appeared first on The Texas Observer.

Leave a Reply