These days, the thrum of traffic and the roar of a bulldozer intrude on conversations at café tables clustered outside the Swedish Hill bakery, an Austin landmark where author Stephen Harrigan and a few writer friends have long gathered to swap ideas. Once Harrigan rode his Trek down the hill to grab a croissant and coffee here for around $1.25; the bill on a recent visit was 10 times higher and the crowded street challenging for cycling. Even this seemingly historic place is a mirage: The café has moved twice. Next door, the bulldozer is busy excavating a huge crater at its prior site.

Change in Austin seems constant, yet Harrigan’s friends maintain their connection. Harrigan credits Lawrence Wright, his Pulitzer Prize-winning neighbor and the breakfast club founder, with inspiring his latest nonfiction book—an exploration of a peasant girl’s visions of the Virgin Mary on a remote mountaintop in Portugal: Sorrowful Mysteries, The Shepherd Children of Fatima and the Fate of the Twentieth Century (Alfred A. Knopf, April 2025).

Harrigan claims he originally intended to write only an article about this devout peasant girl, Lucia, and his long fascination with the secret prophecy she left behind after hearing her story from a nun at Catholic school in Abilene.

But Wright swears that his buddy needed only a nudge. “The mystery of the Fatima prophecies suffused his growing-up years, as it did for most Catholics in that era,” Wright told the Texas Observer. “It seemed a perfect match between a writer and a subject that has been beckoning in the shadows his entire life.”

Harrigan, who was born in Oklahoma City and raised in Abilene and Corpus Christi, is a prolific author of more than a dozen books—novels, nonfiction, essays—and about 40 screenplays, but he’d never before considered writing a memoir. “This is kind of a sideways memoir,” he said. “I haven’t lived a very memoirish life.”

Harrigan, one of the original staff writers of Texas Monthly magazine, claims to be only an accidental journalist. He became a “yard man” and began mowing lawns and writing articles to pay the bills after graduating from the University of Texas in 1970. Ten years later, novels “arose out of magazine pieces”: A story on the ruthless capture of wild dolphins for an aquarium formed his debut Aransas in 1980. The chronicle of an eccentric Italian sculptor who lived in San Antonio and left his legacy carved in statues across the Lone Star State inspired Remember Ben Clayton, his 2012 saga of family pride, loss, and estrangement.

Yet, when he first traveled to the Central Portuguese mountaintop where this peasant girl claimed to have seen her visions—his reporter’s journey became increasingly personal. Harrigan’s connection with Lucia and her two younger cousins, all of whom claimed to have communicated with the Virgin Mary in 1917, intersected with his earliest memories. He and these long-dead Catholic kids had all knelt to recite the same Latin words: Ave Maria, gratia plena… What’s more, he too had fervently believed in the power of a benevolent virgin, as he writes, “usually depicted wearing a blue cloak, her arms open at her sides and her hands open.”

Like them, he grew up believing Mary never perished, but ascended to heaven. He felt moved when he visited the places those children lived and died—and when he strolled through the enormous shrine that stands in the place of a scraggly Holm Oak where they claimed to have seen a holy glowing orb.

The result of that exploration and reportage is a braided narrative of Harrigan’s life, which sees him forsake Catholicism as a UT student in Austin’s slacker years, and of the life of Lucia, the oldest of the three child visionaries and the only one to survive to adulthood. It’s also an exploration of the liturgy, history, and legends surrounding the Virgin Mary, Jesus’ mother, whose place of death remains a mystery for theologians and historians alike. He also explores why so many pilgrims still visit places where she’s supposedly reappeared, including Fatima, Portugal; Lourdes, France; and Mexico City.

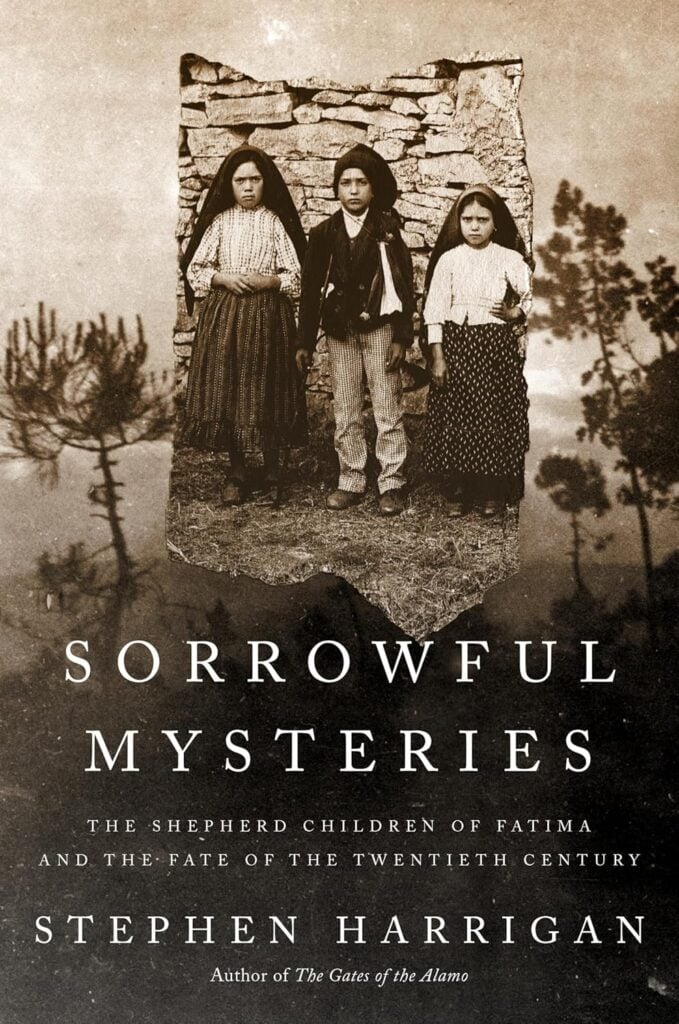

The intriguing tale of Lucia’s secret letter, a prophecy from the Virgin that was given to the pope and was left unopened for decades, is the mystery that captivated Harrigan as a child. But, as an agnostic adult, he dug deeper into the life of the girl, depicted in his book’s cover photo wearing a head covering, a long dark skirt, and a piercing, haunted look. He writes naturally about this visionary, whose accounts of the virgin brought a horde of pilgrims—and financial ruin—to her parents’ grazing land. He writes compellingly of the interrogations and cruelty she faced, which drove her to seek the life of a cloistered nun.

In his work, Harrigan often “seeks emotional linkages.” Bringing a long-dead Portuguese nun to life may seem like a challenge for the happily married father of three who left the church long ago. Yet he has no trouble relating to an impassioned female character, according to another long-time friend, the Austin novelist Elizabeth Crook, who recently collaborated with Harrigan on a screenplay based on The Which Way Tree, her tale of a girl’s quest to hunt down the mountain lion who killed her mother. “Steve just has an innate and uniquely perceptive understanding of human nature. He can put himself into the mind of his characters and intuit their motives with an unusual ease.”

In an outbuilding-turned-studio in Austin’s Tarrytown, Harrigan creates in a space surrounded by walls of books and a lifetime of memorabilia. On one shelf are three plastic dolls of the Portuguese prophet children. On another sits a glass votive featuring the president depicted in his 2017 novel, A Friend of Mr. Lincoln, which imagines a younger Abe as a droll, literary, and only locally famous lawyer.

Just above his office chair is a bumper sticker with the slogan: “Puedes exhumarlo?,” which one of his daughters printed up as a joke after Harrigan mangled the translation of his 1970s catchphrase: “Can you dig it?” He knows that really means: “Can you exhume it?” But, somehow, the slogan still fits a writer who digs up facts in “obscure corners” and writes amid piles of the evidence he’s accumulated.

Perched atop one of the highest bookshelves stand vintage Western figurines, men on horseback representing historical and fictional characters, whom he calls “his oldest friends.” He was 5 when he got the first from his mother’s new husband. (His birth father, a WWII veteran and test pilot, died in a crash when his mother was pregnant with him.)

Harrigan can easily reconnect with memories of his fatherless early boyhood, as he did in his 2022 novel The Leopard Is Loose—plunging into a world where shadows morph into monsters and real and imaginary threats mingle. He knows that visions and spirituality that sprout in a child never truly disappear in an adult. That connectedness lends Sorrowful Mysteries, an unexpectedly universal appeal: Readers simultaneously experience the wonder of childhood and the high price of unfettered belief.

In search of this story—his own and Lucia’s—Harrigan visited the austere cell where the Portuguese peasant girl lived out her adult life in isolation as well as the hospital and mountainside hut where each of her younger cousins perished in the 1917 influenza pandemic.

When he arrived one day on the Sierra de Aire, near the spot where all three claimed to have seen the Virgin, Harrigan experienced his own vision: a shaggy black dog creeping along a trail that connects the glitzy modern Fatima shrine to the humble village where Lucia was born. As he approached, Harrigan’s vision shifted, and he realized the doglike figure was a pilgrim—a woman on her knees crawling in the dirt. She, like him, was searching for the right path.

The post A Texas Writer Tackles a Subject ‘Beckoning in the Shadows His Entire Life’ appeared first on The Texas Observer.

Leave a Reply