By SARA CLINE, Associated Press

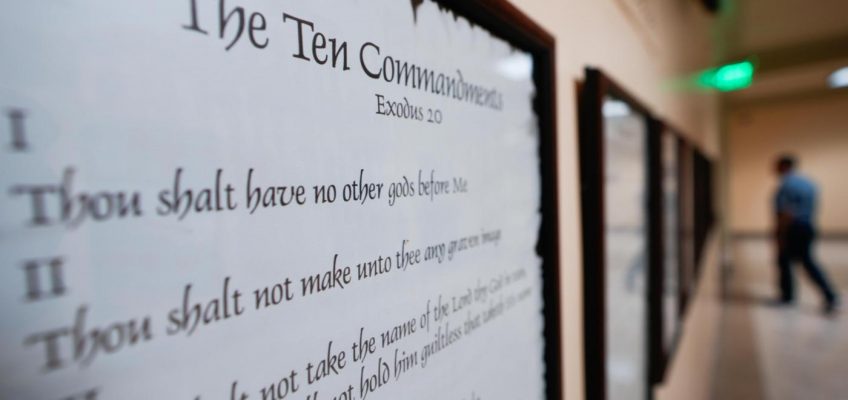

As Louisiana public schools remain in limbo over a new law requiring the Ten Commandments to be displayed in classrooms — caught between the state releasing guidelines for districts to comply with the mandate that took effect this year and opponents threatening to sue if any such posters are hung up — a three-judge panel heard arguments about the controversial legislation Thursday morning.

In the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans, the state is appealing an order issued last fall by U.S. District Judge John deGravelles, who declared the mandate unconstitutional and ordered state education officials not to take steps to enforce it and to notify all local school boards in the state of his decision.

The state contends that deGravelles’ order only affects the five school districts that are defendants in a legal challenge. But it’s unclear whether or how the law would be enforced in the state’s 67 other districts while the appeal progresses.

“I know this needs to be addressed sooner rather than later, and we will do our best to do so,” Judge Catharina Haynes said as arguments concluded Thursday. Haynes did not specify when a ruling would be issued.

The law, which applies to all public K-12 school and state-funded university classrooms, took effect Jan. 1. Days after the mandate went into effect, Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill — the state’s top lawyer — made clear that she expects school districts to comply.

Murrill issued guidance to schools on how to do so, including four samples of the Ten Commandments posters. In addition, each poster must be paired with the four-paragraph “context statement” describing how the Ten Commandments “were a prominent part of American public education for almost three centuries.”

Over the past month, the Associated Press has reached out to dozens of school districts, the Attorney General’s office and the Department of Education and has not been told of any schools that have begun to hang up such posters.

Opponents of the law argue that it is a violation of the separation of church and state, and that the poster-sized display of the Ten Commandments would isolate students, especially those who are not Christian.

Plaintiffs in the suit include parents of Louisiana public school children with various religious backgrounds, who are represented by attorneys with civil liberties groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation.

Proponents say that the measure is not solely religious, but that it has historical significance to the foundation of U.S. law. Additionally, Murrill argues that the lawsuit is premature as posters have yet to be hung up.

The new law in Louisiana, a reliably Republican state that is ensconced in the Bible Belt, was passed by the state’s GOP-dominated Legislature earlier this year. Republican Gov. Jeff Landry signed the legislation in June — making Louisiana the only state to require that the Ten Commandments be displayed in the classrooms of all public schools and state-funded universities. The measure was part of a slew of conservative priorities that became law in Louisiana last year.

The legislation, which has been touted by Republicans including President Donald Trump, is one of the latest pushes by conservatives to incorporate religion into classrooms — from Florida legislation allowing school districts to have volunteer chaplains to counsel students to Oklahoma’s top education official ordering public schools to incorporate the Bible into lessons.

In recent years, similar bills requiring the Ten Commandments be displayed in classrooms have been proposed in other states including Texas, Oklahoma and Utah. However, with threats of legal battles over the constitutionality of such measures, none have gone into effect.

In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a similar Kentucky law was unconstitutional and violated the establishment clause of the U.S. Constitution, which says Congress can “make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” The high court found that the law had no secular purpose but rather served a plainly religious purpose.

Leave a Reply