Lately I have found myself beginning speeches about the foreign policy challenges facing the next president this way: “I want to speak today to all the parents in the room: Mom, Dad, if your son or daughter comes home from college and says, ‘I want to be the U.S. secretary of state someday,’ tell them: ‘Honey, whatever you want to be is fine, but please, please, don’t be secretary of state. It is the worst job in the world. Secretary of education, secretary of agriculture, secretary of commerce — no problem. But promise us that you won’t become secretary of state.’”

The reason: The job of running U.S. foreign policy is far, far harder than most Americans have ever spent time considering. It’s a near-impossibility in an age when you have to manage superpowers, super-corporations, super-empowered individuals and networks, superstorms, super-failing states and super-intelligence — all intermingling with one another, creating an incredibly complex web of problems to untangle to get anything done.

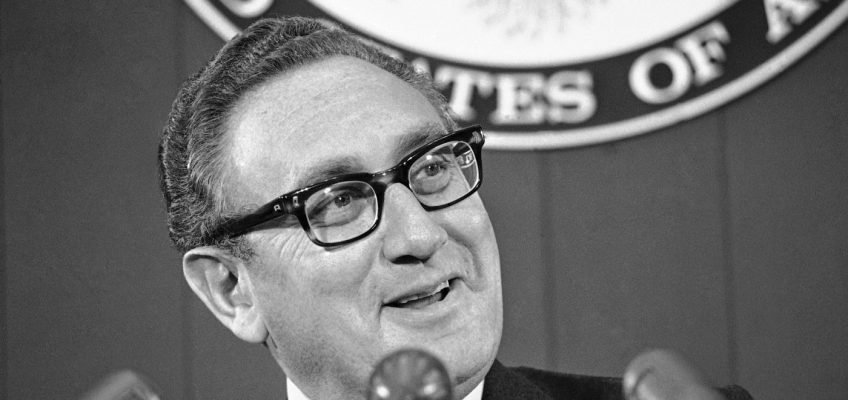

In the Cold War, heroic diplomacy was always within reach. Think of Henry Kissinger. He needed just three dimes, an airplane and a few months of shuttle diplomacy to put together the historic post-1973 October war disengagement agreements between Israel, Egypt and Syria. He used one dime to call President Anwar Sadat of Egypt, one dime to call Prime Minister Golda Meir of Israel and one dime to call President Hafez al-Assad of Syria. Presto: tic-tac-toe — Egypt, Syria and Israel in their first peace accords since the 1949 armistice agreements.

Kissinger was dealing with countries. Antony Blinken was not so lucky when he became the 71st secretary of state in 2021. Blinken — along with the national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, and the CIA director, Bill Burns — have played a difficult hand well, but just compare the Middle East they have had to deal with to Kissinger’s. The region has been transformed — from a region of solid nation-states to one increasingly made of failed states, zombie states and super-empowered angry men armed with precision rockets.

I am talking about Hamas in the Gaza Strip, Hezbollah in Lebanon and Syria, the Houthis in Yemen and Shiite militias in Iraq. Virtually everywhere Blinken, Sullivan and Burns looked when they mounted their shuttle diplomacy after Oct. 7, 2023, they saw double — the official Lebanese government and Hezbollah’s network, the official Yemeni government and the Houthi network, and the official Iraqi government and the Iranian-directed Shiite militia networks.

In Syria, you have a Syrian government in charge in Damascus, and the rest of the country is a patchwork of zones controlled by Russia, Iran, Turkey, Hezbollah, and U.S. and Kurdish forces. The Hamas network in Gaza could be reached only via Qatari and Egyptian mediators. And even Hamas had a military wing inside Gaza and a political wing outside Gaza.

Related Articles

Other voices: Could AI create deadly biological weapons? Let’s not find out

F.D. Flam: AI can debunk conspiracy theories better than humans

David Fickling: Breaking our plastics habit is easier said than done

Katja Hoyer: Germany has gotten more conservative, not more radical

Lyle Goldstein: What can the U.S. do to stabilize its relationship with China?

Meanwhile, Hezbollah is the first nonstate entity in modern history to have established mutual assured destruction with a nation-state. Hezbollah today can credibly threaten to destroy Tel Aviv Airport with its precision rockets every bit as much as Israel can threaten to destroy Beirut Airport. That was not true the last time they fought a war, in 2006.

What was also not true back then was that Israel would have technology to kill or wound hundreds of Hezbollah members in one fell swoop, as it did Tuesday by using “Matrix”-like cyber tools to detonate their pagers at once — while U.S. diplomats were working feverishly on a cease-fire between the two parties. So just when U.S. diplomats are trying to quiet the battlefield in physical space, the one in cyberspace erupts.

Goodbye, tic-tac-toe. Today, getting the interests of all these entities aligned at once to secure a cease-fire in Gaza is as easy as getting all the same colors lined up on one side of a Rubik’s Cube.

We need a lot of allies

So, there is only one thing clear to me about this new world of geopolitics that our next president will have to manage: We need a lot of allies. This is not a job for an “America alone.” It is a job for “America and friends.”

That is why the choice in this election for me is also clear. Do you want Donald Trump — whose two bumper-sticker messages to our allies are basically “Get off my lawn” and “Pay up, or I’ll hand you over to Putin” — as president or Kamala Harris, who comes out of a Biden administration whose signature foreign policy achievement has been its ability to build alliances? That is Joe Biden’s greatest legacy, and it is a substantial one.

In the Asian-Pacific, the Biden team used alliances to counterbalance China militarily and technologically. In Europe, it used them to counter the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In the Middle East, it used them on April 13 to shoot down virtually all 300 or so drones and missiles that Iran fired at Israel. And in covert diplomacy, it gathered our allies for the complex, multination prisoner swap that freed, among others, Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, dishonestly jailed by Vladimir Putin.

What is the No. 1 reason that Russia, Iran and China all want Trump elected? Because they know that he is so transactional when it comes to dealing with NATO and other U.S. allies that he can never assemble sustainable alliances against them.

Helpful reading: “Titans of the Twentieth Century”

Have no doubts: The world in which our next president and secretary of state will have to lead is more challenging than at any time since before World War II. That is why I have found it quite helpful now to be reading a new book just out by Michael Mandelbaum, titled “The Titans of the Twentieth Century: How They Made History and the History They Made,” a study of the impact on history of Woodrow Wilson, V.I. Lenin, Adolf Hitler, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Mohandas Gandhi, David Ben-Gurion and Mao Zedong.

The chapters on Churchill and Roosevelt are particularly relevant to the present. These two greatest democratic leaders of the 20th century recognized the dictatorships in Germany and Japan early on for what they were — and knew that they threatened Britain and America. But what they also understood was that neither of their countries could have won World War II alone (or without the Soviet Union). Alliances were crucial.

“Maintaining alliances is never easy,” Mandelbaum told me. “Churchill and FDR were not personally as close as they have often been portrayed as being and had important political disagreements. Each understood, however, that he needed the other, and they made their partnership work. Maintaining and strengthening America’s global partnerships in the face of a dangerous world will be a major task for the next commander in chief.”

This is especially true at a time when we are not as prepared militarily for the world we’re entering as we need to be.

Add others’ strength to our own

Russia, Iran and China have all been engaged in significant military buildups for years. We, by contrast, literally lack the weaponry today to fight on all three fronts at once. The only way to cope with that potential problem is not to abandon one or more of these regions but to add others’ strength to our own via alliances, which was, as it happens, the key to our success in the two World Wars and the Cold War.

Also, “a leader sometimes has to ask for sacrifice,” Mandelbaum added. “That request can only be effective if the leader has a reputation for credibility. And credibility, in turn, requires candor.” Both Roosevelt and Churchill “communicated the choices their countries faced clearly, honestly and eloquently.”

Here, I have to say, Trump still may have an advantage. He is honest about his awful views. He’s signaled that he does not care whether Ukraine wins or loses to Russia. Unfortunately, when Harris was asked at the debate, “Do you believe you bear any responsibility in the way that withdrawal played out” in Afghanistan that led to the deaths of 13 U.S. service members, she totally dodged the question. Big mistake. I’m certain that undecided voters noticed that — not to Harris’ advantage.

Her answer should have been: “I was gutted by those deaths. I will never forget hearing the news in the Situation Room, because that is where the buck stops. But most of all I will never forget what I learned from that experience. It will never be repeated in my presidency.” She would have won votes with an answer like that — from voters who worry that she’s much more “left” than she lets on.

Alas, there’s another reason China prefers Trump. He not only detests illegal immigration; as president he cracked down on legal immigration to appeal to right-wing nativists. That’s music to China’s ears. It weakens America’s key advantage over China — our ability to attract talent from everywhere.

For instance …

For instance, how many Americans know that the U.S.-led artificial intelligence revolution made a giant leap forward in 2017 when Google released to the world one of the most important technology algorithms ever written? It established a deep learning architecture — the “transformer” — for processing language that “kick-started an entirely new era of artificial intelligence: the rise of generative AI,” like Bard and ChatGPT, as the Financial Times put it.

That algorithm was written by a team of eight Google AI researchers in Mountain View, California. They were, the Financial Times noted: Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Jakob Uszkoreit, Illia Polosukhin and Llion Jones, “as well as Aidan Gomez, an intern then studying at the University of Toronto, and Niki Parmar, a recent master’s graduate on Uszkoreit’s team, from Pune in western India. The eighth author was Lukasz Kaiser, who was also a part-time academic at France’s National Centre for Scientific Research.”

Their “educational, professional and geographic diversity — coming from backgrounds as varied as Ukraine, India, Germany, Poland, Britain, Canada and the U.S. — made them unique,” the Financial Times wrote. It was also “‘absolutely essential for this work to happen,’ says Uszkoreit, who grew up between the U.S. and Germany.”

Needed: more candor from Harris

I’m sure Harris is up to the job of commander in chief. But more candor from her now — to show that she has the steel to take on the most impossible foreign policy challenges and take on her own progressive base if she needs to — would convince more undecided voters that she has the steel to take on Putin.

As for Trump, he is strong and wrong on the two key foreign policy issues — alliances and immigrants. His default option — America alone — is a prescription for America weak, America isolated, America vulnerable and America in decline.

Related Articles

Other voices: Could AI create deadly biological weapons? Let’s not find out

F.D. Flam: AI can debunk conspiracy theories better than humans

David Fickling: Breaking our plastics habit is easier said than done

Katja Hoyer: Germany has gotten more conservative, not more radical

Lyle Goldstein: What can the U.S. do to stabilize its relationship with China?

Thomas Friedman writes a column for the New York Times.

Leave a Reply