There’s a Minnesota native in the Baseball Hall of Fame who was known for his clutch pitching in the World Series — the pitcher who couldn’t be dragged from the mound even when the biggest games stretched past the ninth inning.

And that’s not even counting Jack Morris.

You’ve probably read a few times this week that Joe Mauer is the fourth St. Paul native to be inducted into the Hall, along with Dave Winfield, Paul Molitor and Jack Morris. It’s an incredible claim for the city — especially when considering the entire state has produced only one other hall of famer born here.

RELATED: St. Paul vs. Mobile, Alabama: Which is the capital for Hall of Famers?

On Monday morning, after the streets of Cooperstown were open again and most of the crowds had left, still basking in the memories of Mauer, Beltre, Leyland and Helton, I went back to the Hall to find that fifth Minnesotan native’s plaque and found him right there between Dizzy Dean and Paul “Big Poison” Waner.

Charles Albert Bender.

And right under that, the nickname that (almost) everyone in baseball called him, the nickname he disdained.

“Chief.”

Charles Bender was born in Crow Wing County in 1884, exact day and location unknown, and grew up on the White Earth Reservation in northern Minnesota. His mother was Ojibwe and his father German. His family was large and poor, and young Charles probably didn’t play baseball until after he’d been sent to the Carlisle boarding school in Pennsylvania, a place designed to “assimilate” Native American children into the dominant white culture. Bender later said, though, that he had unknowingly begun his training as a pitcher by throwing rocks at gophers on the reservation.

After being sent east, Bender rarely returned to Minnesota throughout the rest of his life, but he put together one of the more unlikely Hall of Fame careers in baseball history.

At Carlisle, he became a pitcher under the coaching of Pop Warner. He joined Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in 1903 and defeated Cy Young in his first game, and was a rising star by 1905. That’s when he began a remarkable run as a big-game pitcher. In the 1905 World Series, he pitched a shutout in Game 2 to beat future hall of famer Joe McGinnity, and he pitched another complete game in Game 6, though he and the A’s lost to one of the greatest ever, Christy Mathewson, who threw three shutouts in three starts for the New York Giants.

Bender had established himself as Mack’s go-to pitcher for big games, in an era when Mack had hall of famers such as Rube Waddell and the great “Gettysburg Eddie” Plank on his rosters.

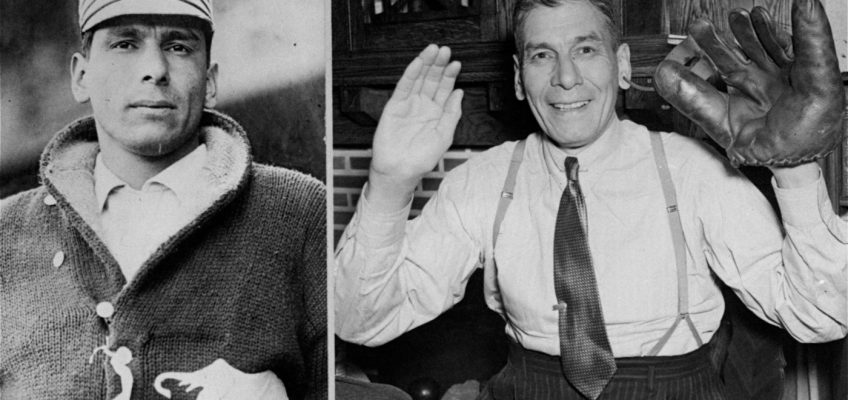

Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Charles Bender is seen in this 1909 photo. He won six World Series games and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1953. (Associated Press)

When Philadelphia next reached the World Series in 1910, Bender was Mack’s choice to start Game 1 over 31-game-winner Jack Coombs. Bender rewarded him with a complete-game victory. He lost Game 4 in a duel with “Three-Finger” Brown of the Cubs, but again Bender threw a complete game – all 10 innings. The Athletics won the series the next day.

Bender was again Mack’s choice over Plank for Game 1 of the 1911 Series, a rematch against Mathewson and the Giants. Mathewson prevailed again, 2-1, though Bender went the distance, of course. He finally beat Mathewson in Game 4 with a 2-run complete game. Then Bender returned to the mound two days later to throw another 4-hit complete game to clinch the championship.

Bender again started Game 1 of the 1913 World Series and also Game 4, winning both and going the distance each time (also pitching for the A’s in that series was Brainerd native Bullet Joe Bush).

It wasn’t until 1914 that Bender faltered, losing Game 1 and failing to finish a World Series start for the first time, and the Giants lost the series in an upset. Mack let him go after that, as he sold off and dismantled the Philadelphia dynasty that was about to become a lot more expensive.

Bender succeeded on the mound largely through his command of the strike zone, his large and varied repertoire of pitches, and his ability to read and exploit batters’ weaknesses. His knowledge of the game and attention to detail put him in demand as a major-league pitching coach in the second half of his life — especially his ability to pick up small “tells” that gave away opponents’ intentions.

Bender also might have invented the slider — though it was often called a “nickel curve” in his day.

Bender bounced around the league a bit after Mack let him go, though his glory years in big-league baseball were over. He kept pitching for years with minor league and semipro teams, and was in demand as a coach in the major leagues as the decades went on. He was also at the wheel when his car struck a man crossing a Philadelphia street, killing him, but after a controversy over whether Bender left the scene or had been sent away by a police officer, charges were dropped against him.

In an era of fiery, hard-fighting and foul-talking ballplayers, Bender was known for his cool and unflappable demeanor, especially under pressure, a trait he might have honed originally to deal with the abuse he encountered as an Ojibwe man competing in the “white” big leagues.

Tom Swift, a writer in Northfield, Minn., wrote a 2008 biography of Bender, “Chief Bender’s Burden,” that goes into wincing detail about the racism and prejudice Bender faced as an Ojibwe man. Though he was allowed to play in the “white” major leagues at a time Black ballplayers couldn’t, he still faced all the predictable taunts, slurs and slights from fans and opponents.

It’s all painful and infuriating to read, of course — but a strange thing happens as the book goes on. The prejudice doesn’t disappear, but as Bender goes through his life in the overwhelmingly white world of professional baseball at the time, he just keeps quietly winning over people, turning people who at first see him at best as some sort of mascot into lifelong friends. The quotes of esteem and respect from teammates and opponents pour out as the years go on.

Bender lived long enough to know that he had been inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1953, though he died before the ceremony and didn’t have to wince at seeing “Chief” on that plaque.

In the biography, Swift points out that just about every one of the few Native American players in the big leagues in this era was saddled with the “Chief” nickname. Bender was no different — though he spoke out against the moniker: “I do not want my name to be presented to the public as an Indian, but as a pitcher.”

But he eventually, grudgingly, surrendered to it, allowing it even on his gravestone. And it’s there on his Hall of Fame plaque.

Pitcher Charles Bender’s plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame, photographed on July 22, 2024. (Mike Decaire / Pioneer Press)

There was at least one baseball person who didn’t use the nickname, at least not around Bender. His longtime manager and friend Connie Mack called him “Albert,” his middle name and the last name Bender was playing under to preserve his amateur status at the time Mack acquired his contract.

Mack also said something else:

“If everything depended on one game,” Mack said, “I just used Albert.”

“From St. Paul to the Hall”: the Pioneer Press chronicled the careers of Dave Winfield, Paul Molitor, Jack Morris and Joe Mauer, and we’ve compiled the best of our coverage into a new hardcover book that celebrates the legendary baseball legacy of Minnesota’s capital city. Order your copy of “From St. Paul to the Hall.”

Related Articles

Video: Watch as Joe Mauer’s plaque goes up in the Hall of Fame

Appreciation runs deep, on both sides, for Hall of Famer Joe Mauer

From St. Paul to the Hall: Twins legend Joe Mauer inducted into Hall of Fame

Joe Mauer’s Hall of Fame plaque says it all in two words: ‘Lifelong Twin’

‘From St. Paul to the Hall’: All eyes on high schooler Joe Mauer

Leave a Reply