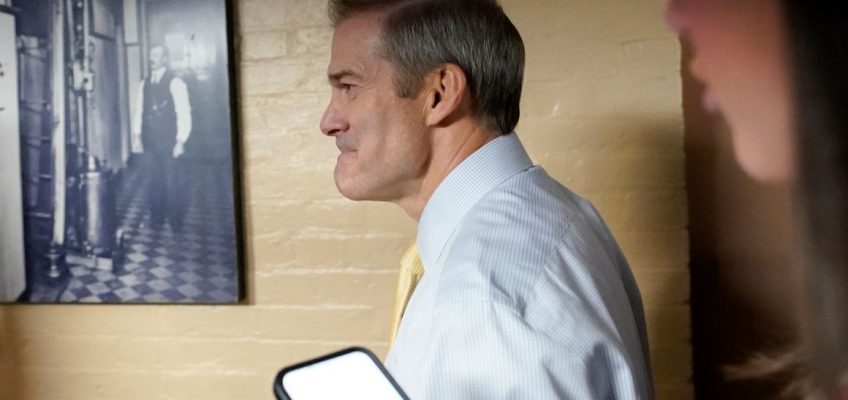

Jim Jordan’s improbable rise to the cusp of Capitol Hill’s top job has delighted many conservatives, who see an accomplished infighter bent on impeaching President Joe Biden.

He’s a model presence on Fox News during an era in which success for many Republicans is measured in cable news hits, instead of old-fashioned legislating. His installation as speaker would mark the first time the GOP’s top lawmaker hailed from the party’s growing hard-right contingent. He’s in good standing when it comes to one of the GOP’s most important yardsticks — his relationship with former President Donald Trump.

Yet for all those reasons and quite a few others, he would be badly miscast as speaker of the House, and Republicans should be relieved he has, for now, fallen short of the votes. Jordan on Thursday abandoned a third speaker’s ballot for the moment, instead endorsing a measure to let acting Speaker Patrick McHenry (R-N.C.) run the House temporarily.

Set aside the fact that Jordan has virtually no legislation to his credit despite 17 years in Congress. The speaker’s job requires a very particular set of skills — an ability to build bipartisan coalitions, to work with one’s adversaries, and to learn to accept half-victories. That makes it a particularly crummy job for Jordan because the very essence of the position requires compromises that are anathema to the right wing and to the conservative media ecosystem that powered his ascent.

In this moment, there are violent thunderstorms on the horizon — the job comes with a daunting roster of unfinished must-do business, including keeping the government open and providing tens of billions of dollars in aid to Israel and Ukraine. Passage of a bipartisan stopgap funding law last month cost then-Speaker Kevin McCarthy his job; Jordan opposed it.

Jordan’s critics worry that he would allow Trump to meddle in House business, an especially worrisome prospect since Trump, as president, drove the government into a lengthy shutdown in 2018-19 only to emerge empty-handed.

Then there’s the question of which Jordan would Washington get? There’s the prototype who, in a prior time, helped orchestrate government shutdowns and was once described by former Speaker John Boehner, a fellow Ohioan, as “a legislative terrorist” and an “asshole.”

Then there’s the pragmatic insider version who embarked on a leadership track a few years back, forging a close relationship with McCarthy. He sided with McCarthy earlier this year by voting for a debt limit deal that the California Republican made with Biden. He’s managed to win support from GOP pragmatists like Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Ala.) after promising that he would shepherd passage of must-do legislation including defense policy, agency budgets, and next year’s reauthorization of food programs and farm subsidies.

Previous GOP Speakers like Boehner and Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) came from the party’s governing wing. Boehner worked with Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) to pass the No Child Left Behind education law in 2002; Ryan negotiated a 2013 budget accord with veteran Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) and went on to chair the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee.

Jordan has nothing remotely similar on his résumé. Now he’s hoping to get thrown in the deep end, taking on a Democratic president and a twin Senate threat of top Democrat Chuck Schumer and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), who are allied against Jordan on aid to Ukraine and government spending levels. Jordan has vilified Schumer in the past and has virtually no history with McConnell.

Conflict in the Middle East has further upended the equation. Biden is sending Congress a huge aid package request for both Israel and Ukraine; Jordan is a skeptic of Ukraine aid and his party is badly split on the question.

A pessimistic take on Jordan is that he’d simply be unwilling to cut compromises with the Senate and the Biden White House, especially as the House slides toward a possible Biden impeachment. A partial government shutdown is in the offing if gridlock hits.

For those seeking it, there’s ample evidence in Jordan’s past battles with leadership figures such as Boehner to suggest he won’t play well with others now. Jordan helped drive Boehner from the speaker’s chair in 2015. He and other Freedom Caucus figures gave Ryan fits during the first two years of the Trump administration, including a drawn-out battle over repealing Obamacare that almost led Ryan and Trump to abandon the idea. Instead, the repeal died in the Senate.

When Boehner quit the speaker’s chair he left himself time to “clean out the barn” — passing politically difficult bills like a debt limit increase before handing the gavel to Ryan.

Now, the barn is a mess. Jordan wouldn’t get the grace period afforded Ryan. Critical deadlines loom. Hard feelings permeate the competing leadership camps of Jordan and Majority Leader Steve Scalise. (Scalise bowed out of the speaker’s race despite besting Jordan in a nominating ballot, complaining about bad faith from Jordan partisans.

More than 20 Republicans, however, including several from the compromise-seeking Appropriations Committee, have united to block Jordan’s path in two separate votes this week.

Some of the pressure tactics employed by Jordan supporters irritated holdouts such as Appropriations Chair Kay Granger (R-Texas), a leadership loyalist whose opposition raised eyebrows. “This was a vote of conscience and I stayed true to my principles,” Granger wrote on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter. “Intimidation and threats will not change my position.”

McHenry may now end up cleaning out the barn, but it’s clear Republicans would still be mistaken if they handed power to Jordan afterward.

Leave a Reply