The number of drug overdoses inside Department of Homeless Services shelters reached new heights in the second half of 2021, though staff and clients managed to reverse more than 90 percent of the overdoses.

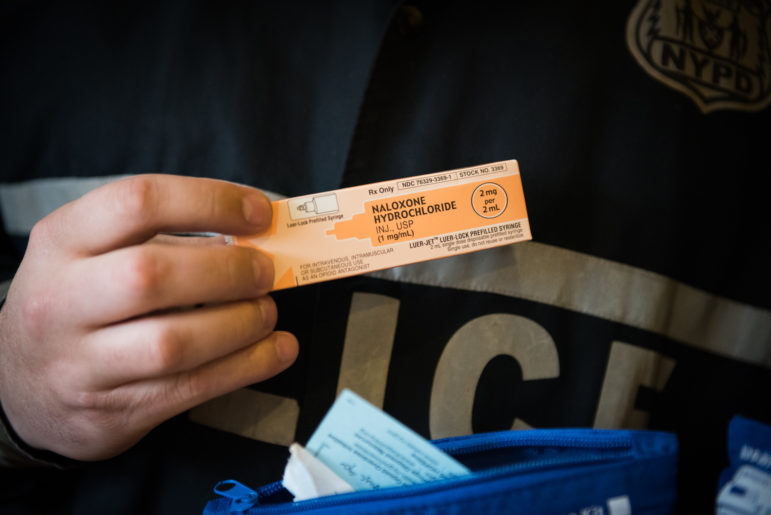

Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office

Naloxone, a rescue dosage for opioid users who overdose.

A worsening nationwide opioid crisis is taking a heavy toll on New York City’s homeless population, with the number of overdoses inside city shelters reaching new heights in the second half of 2021, records show.

Staff working in Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters recorded 632 overdoses in the six months between July 1 and December 31, 2021—the months immediately following the deadliest fiscal year on record for unhoused New Yorkers—according to statistics shared with City Limits in response to a Freedom of Information Law request. That’s up from 364 in the final six months of 2020 and 359 in the last half of 2019.

Overall, there were 1,091 overdoses recorded in DHS shelters in 2021, a 76 percent increase compared to 2019. In November 2021, the most dangerous month for people who use drugs, at least 106 people overdosed in single-adult shelters, the records show.

The rate of overdose has prompted immediate action from DHS and has spurred calls for more effective federal, state and local strategies to keep drug users safe amid a nationwide spike in overdoses and drug-related deaths fueled mainly by Fentanyl-laced opioids.

Julia Savel, a spokesperson for the Department of Social Services, which oversees DHS, said staff, emergency responders and other shelter residents managed to reverse 93 percent of the overdoses inside shelters using naloxone nasal spray last year.

“New York City’s pioneering and model approach on harm reduction continues to save lives amid a nationwide opioid crisis and overall pandemic-related increase in substance use challenges,” Savel said, adding that the agency is “equipping all of our shelter sites with dedicated supports to protect the health and safety of our clients.”

Staff submit an incident report for a suspected overdose when they encounter a person who is unconscious and is known to use drugs, as well as when they administer naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan.

In 2021, shelter staff administered naloxone 1,107 times and emergency responders used the spray inside shelters another 137 times, DHS said. Since 2016, staff, residents and emergency workers have administered naloxone about 3,300 times inside shelters.

The agency declined to say how many people who overdosed in shelters died in the second half of 2021 and said the information will be available in the next annual homeless deaths report, which is published around January by DHS and the Health Department and covers the fiscal year that ended six months earlier. The most recent report showed that 237 homeless New Yorkers died from overdoses in the months between July 1, 2020 and June 30, 2021, marking a dramatic rise in fatal drug use and contributing to the deadliest year for unhoused residents since the agencies began compiling their report.

Overall, 640 New Yorkers died while experiencing homelessness in the 2021 fiscal year, the report found. During that period, staff working in DHS shelters submitted 823 overdose-related incident reports.

Overdose statistics reveal the disproportionate impact on New Yorkers experiencing homelessness, who make up less than 1 percent of the city’s population but appear to account for about 10 percent of the overdose death toll.

Across New York City, roughly 2,500 people died from a drug overdose in the 2021 calendar year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease and Control. If the overdose death rate among homeless New Yorkers in the first six months of 2021 continued through the full calendar year, it would mean 1 of every 10 people who died from an overdose was homeless at the time.

Around 16,300 single adults stay in DHS shelters each night, according to daily reports tracked by City Limits. People staying in single adult shelters accounted for the vast majority of overdoses last year, though a rising number of overdoses also occurred in so-called Safe Haven shelters for people coming in from the streets.

Dr. Kelly Doran, an emergency physician who runs the Health x Housing Lab at NYU Langone, said New York City reflects the nationwide rise in overdoses and drug-related deaths among people experiencing homelessness. The Health x Housing Lab focuses on the health benefits of permanent housing and provides evidence-based strategies for improving health, including reducing overdoses, among individuals experiencing homelessness.

Doran urged city, state and federal agencies to make deeper investments in strategies that make it safer for people who use drugs while easing access to opioid replacements and pathways to recovery.

“In the end, the drug supply is unpredictable and unsafe right now, and criminalization doesn’t work,” she said. “We need safer supply and real harm reduction—things like supervised consumption sites.”

Two supervised consumption sites, also known as Opioid Prevention Centers (OPCs) that opened earlier this year have provided people in East Harlem and the South Bronx with a safe setting in which to use drugs while receiving additional medical and recovery treatment.

On Wednesday, Mayor Eric Adams said the city will use $150 million it received as part of a state settlement with opioid manufacturers to open additional OPCs and fund additional harm reduction strategies, including Street Health Outreach and Wellness (SHOW) mobile clinics and syringe exchanges.

DHS officials said they have no plans to introduce OPCs inside shelters where drugs are banned, but said they will use a new grant from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to establish a Harm Reduction Advisory Council, update policies to make them less punitive and provide Fentanyl test strips to shelter staff.

In an interview with City Limits, DHS Medical Director Dr. Fabienne Laraque said the agency is collaborating with the city Health Department and state agencies to run mobile methadone clinics and increase delivery of methadone, which acts as a non-lethal replacement for opioids.

Laraque urged the federal government to eliminate a requirement forcing physicians to undergo training and obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, another opioid replacement medication.

"Anybody can prescribe an opioid but not everybody can prescribe buprenorphine," she said.

While comprehensive prevention strategies may lag, city agencies and nonprofits have become adept at responding to an overdose. DHS said it has distributed more than 66,000 naloxone kits in shelters, most of which are run by nonprofit organizations with city contracts. Officials said they have also trained about 14,200 staff members and more than 17,150 shelter residents to administer the life-saving nasal spray. The medication temporarily reverses the effects of an overdose by blocking opioid receptors.

Samuel Irving, a resident of a Bronx shelter, said he recently used naloxone on a man he found unconscious inside the shelter bathroom earlier this month.

“I saw a guy in there almost done,” Irving said. “If I hadn’t hit with the Narcan and called the ambulance, he’d be dead.”

Irving said he received naloxone training while staying at a veterans shelter and carries a kit with him because he frequently encounters people who use heroin and other opioids.

Edwin J. Torres/NYC Mayor’s Office

An overdose prevention kit.

City Limits talked with nonprofit staff members at three shelters in Queens and Manhattan who said workers and residents have encountered people who have overdosed and intervened with naloxone.

“It’s been crazy with this Fentanyl,” said an administrator at a single men’s shelter who was not authorized to speak to the media.

A social service staff member at a women’s shelter said the naloxone training and accessibility seems to be working. “We are all trained regularly and carry Narcan [and] have Narcan kits in various places around the facility in the case of suspected overdose,” the person said.

But staff, residents and city officials interviewed for this story said the key is addressing the root causes of substance use and making it easier for people to access and stick with treatment.

“The stress people feel while being in shelter has caused many to relapse,” said Milton Perez, an activist with VOCAL-NY and former shelter resident who moved into an apartment last year.

He said the best treatment is permanent housing mixed with behavioral and medical support to prevent people who are isolated from fatally overdosing.

Perez also urged shelter staff to inform residents when a person overdoses or dies to protect others.

“People die one day from drugs, nothing is said,” he said. “And the next day someone dies probably from the same package of bad drugs.”

Leave a Reply